By Bob Grainger –

Last month’s column was about the use of wood as a heating source and the dangers of house fires. The focus of this month’s is the use of coal and later, electricity, and some of the risks associated with its use in the last century.

Coal stoves became increasingly popular in the closing days of the 19th century and into the early 20th century. Coal was a more concentrated energy source, it was delivered to the house, and unlike wood, it did not need to be split and stacked.

There were many grades of coal – from the softer lignite and bituminous coals to the harder anthracite, the latter burning at a higher temperature and with a smaller amount of smoke. There were several local sources of coal in Kitchissippi: M.N. Cummings Lumber Yard at Churchill and Scott, Independent Coal and Lumber at Scott and Lanark, and Leafloor Coal and Ice on Richmond Road at Cleary Avenue. These coal dealers stocked about a dozen different types of coal, depending on the type of stove and the wishes of the consumer. At the M.N. Cummings Lumber Yard, the 250-foot long coal storage shed was located along the north side of a railway siding from the Canadian Pacific mainline.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, it was common for the children of less fortunate families to walk the railway right-of-way looking for and collecting chunks of coal that had fallen from the passing steam locomotives. Many depended on this source for a significant share of their fuel.

There were several dangers that had to be considered in the use of coal as a home-heating fuel, dangers which quite frequently led to house fires. The first of these was coal gas, a gas which was released when coal was first exposed to heat. Normally, this gas, when exposed to an open flame, would burn away harmlessly. But if there was no flame in the stove when the coal was added, then this coal gas could accumulate and then explode when a flame appeared to ignite it. This gas could also seep from the stove into the house and cause asphyxiation.

The second danger lay in the process by which a coal-fired stove was activated each morning. In many households, the father of the family would be the first person to rise. He would add fresh coal to the top, watch for the coal gas to burn off, and then open the vents in the front of the stove to allow a great deal of air to enter the stove to speed the ignition of the new coal. But these vents could only remain open for a few minutes. If for any reason these vents were left open, then the greater supply of oxygen would cause the coal to burn very rapidly and very hotly. The pipes at the back of the stove would become red hot and lead to fires in the surrounding walls.

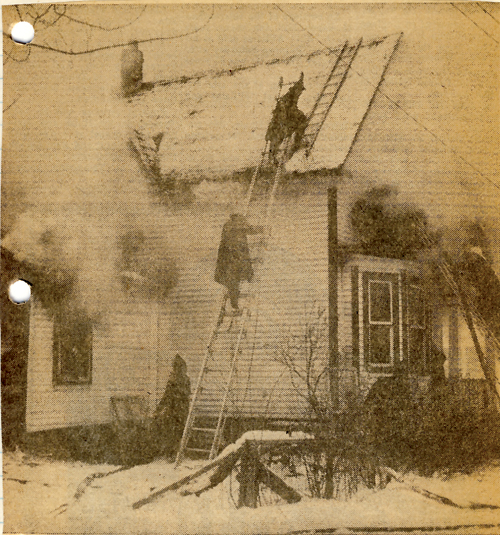

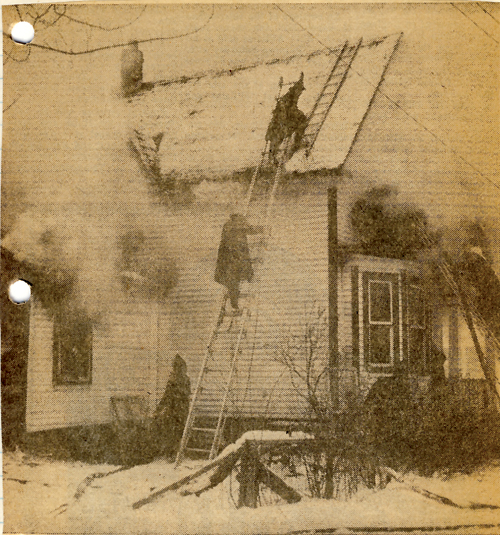

In mid-January of 1956, the population of Ottawa worried about a string of terrible winter house fires. In fact, in many households, parents were taking turns staying awake to safeguard their families. Thirty-two people had died in house fires since November 1, and the three worst fires all happened in Kitchissippi. The first of these was on Marjorie Street (now part of Westhaven Crescent), which claimed the lives of five children and one adult. The second occurred on the west side of Northwestern Avenue north of Pontiac Street, which took the lives of five children. The third fire was on Tweedsmuir Avenue, which killed three children and one adult. In two of these fires, it was suspected that the freshly started coal fire in the stove was allowed to increase in intensity for too long a period, and the red-hot stove pipes ignited fires in the walls.

Don Skemer, who had joined the Fire Department in the early 1950s, and who was born and raised in what is now known as Champlain Park, remembers this as a very difficult time for himself and his firemen colleagues.

Electricity comes to Kitchissippi

Electricity first came to Ottawa in the early 1880s and was used for street lighting and industries centred on the Chaudiere Falls, the site of the first hydraulic generators in Canada. Gradually, electricity was made available for home use, starting with lighting. New residential construction included safe electrical wiring, but for older housing power was often installed in a questionable manner by the owner or a neighbourhood handyman. And at the same time demand for electricity grew – for more lighting, but also for other uses that put much greater demands on the wiring system in the house.

Fire hazards arose when circuits were overloaded, in other words, when more electrical power was demanded from a circuit than it was designed to carry. “Over-fusing” was a common occurrence and a frequent cause of house fires, and occurred when owners would replace a 15-amp fuse with a 20- or even a 30-amp fuse, thus completely bypassing the protective feature of the fuse. The circuits would overheat and ignite surrounding materials. Circuit breakers provided an answer to this problem, but there were many older homes with the older electrical systems based on fuses.

Electrical problems were implicated in a serious fire on the west side of Northwestern Avenue just north of Pontiac Street in January of 1956, which resulted in the death of five children. At the inquest, the mother of the family testified that she would often experience uncomfortable electrical shocks when she was scrubbing the kitchen floor. The house was incompletely finished with no plaster or wallboard, only cardboard – so when the fire started, it very quickly raced through the entire building.

Bob Grainger is a retired federal public servant with an avid interest in local history. KT readers may already know him through his book, Early days in Westboro Beach – Images and Reflections. He’s also part of the Woodroffe North history project and is currently working on the history of Champlain Park and Ottawa West. Do you have any memories to share about home heating in early Kitchisisppi? If so we’d love to hear them. Send your email to stories@kitchissippi.com.