By Bob Grainger –

In the latter part of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century, home heating technology was such that it involved some real risks in terms of house fires. In these early days, “home heating” really meant “stove heating.”

The stove was in the kitchen (for cooking), and the further that you got from the kitchen and the stove, the less warmth you felt. (In a largely futile and also dangerous attempt to distribute heat beyond the kitchen, the stove pipe was conducted through as many rooms as possible on its trip to the outdoors.)

In the latter half of the 19th century, and for poorer families into the 20th century, the fuel of choice was wood. For the poorer families living along the Ottawa River, it was terribly tempting to appropriate one or two logs from the river, cut them up, dry them out, and burn them for heat. But these logs were valuable to the lumber companies, and to keep losses to a minimum, they had their rivermen search out errant logs in the quiet reaches of the river.

This was the rule: people were only allowed to take the “deadheads,” but nothing else. (Deadhead was the term used for logs which had been in the water for so long that only one end would rise above the water’s surface.)

The problem with the use of wood as a fuel is that it produces creosote, especially in inefficient fireplaces and stoves. This creosote would be deposited on the insides of the chimney, and unless it was regularly removed, would build up to the point where it would sometimes catch fire.

Lorne Parker lived with his family on the southwest corner of Pontiac Street and Patricia Avenue in what is now Champlain Park. In his youth, it was his assigned job in the family to remain vigilant to the first signs of a chimney fire, and when a problem developed, to grab a pail of water, rush outside, climb a ladder up to the roof, and pour the pail of water down the chimney! It’s worth noting that these trips up the ladder took place in the cold of winter, because that was when the stove was in constant and serious use.

Chimney fires were quite common and often spread to the roof and the walls of the house, requiring the rapid intervention of the local fire department. Don Skemer grew up on Carleton Avenue in the 1930s and 1940s, and joined the Ottawa Fire Department in the early 1950s. He remembers attending many chimney fires in the west end of the city. He says the process was to initially spray a small amount of water down the chimney to put out the fire because the application of too much water to the very hot chimney would cause the bricks to explode. It was a delicate operation. When the fire was out, the firemen would lower and raise a heavy chain in the chimney to loosen the creosote, and caution the homeowners to clean their chimney and stove pipes at least once a year. At one time the fire department talked about charging for chimney cleaning services, but private chimney sweep businesses came into existence to provide this service.

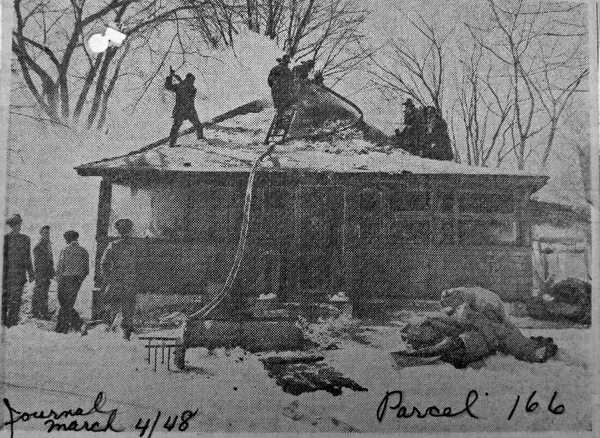

The riverfront areas in Kitchissippi were particularly prone to house fires because the houses were originally built for summer use and had no insulation. At the end of the war in 1945, there was a serious housing shortage for returning veterans – to the point that one veteran was camping out in Tunney’s Pasture in protest. In this situation, these lightly built and uninsulated summer cottages were brought into service as year-round housing. Heating systems were often not up to the job of putting out enough heat to keep residents warm in the cold winter temperatures. There were several serious fires along the river between Woodroffe Avenue and Mechanicsville. One of these, pictured here, took place in Westboro Beach and claimed the life of two young boys in March of 1948.

Next month we’ll take a closer look at the fire hazards of coal-fired heating systems and problems associated with the early use of electricity in the home.

Bob Grainger is a retired federal public servant with an avid interest in local history. KT readers may already know him through his book, Early days in Westboro Beach – Images and Reflections. He’s also part of the Woodroffe North history project and is currently working on the history of Champlain Park and Ottawa West. Do you have any memories to share about home heating in early Kitchisisppi? If so we’d love to hear them! Send your email to stories@kitchissippi.com.