As we approach a full year of living in a pandemic, one of the hardest adjustments for many of us has been the loss of our physical activity routines. With extended closures of gyms, community centres, sports leagues and schools, Kitchissippi residents have turned to traditional outdoor recreation options more than ever to help get through these challenging times.

Local rink and trail volunteers are getting well-deserved extra kudos this year for managing operations under constantly changing regulations. And it is with those generous individuals in mind that there could be no better topic for “Early Days” this month than the history of local outdoor winter fun.

By the 1860s, ice skating had become a popular new trend in cold-weather countries. For a relatively small cost, a person could purchase a specially-made blade that was tied to a regular boot, creating instant skates! (Later, a clamping or screw-in blade was offered, which was not immediately popular, as it required the sacrifice of a pair of shoes as skates).

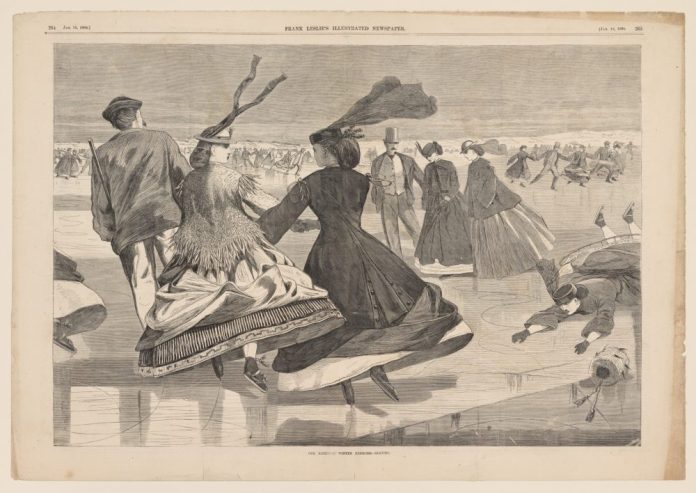

What made skating so appealing was that it was one of the few recreational activities of the era which was enjoyed by men and women, young and old, rich and poor — people of every background, sharing in the same pastime together.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, a popular 19th century American magazine, called skating the “National Winter Exercise,” and in Ottawa, the situation was no different. The phenomenon caught on as citizens made their way onto the Ottawa River and the canal on skates.

Ottawa merchants began stocking skates, and it became fashionable for politicians and the wealthy to host skating parties. Evening skating was occasionally made possible by the arranging of trains at a station, or roundhouse, near the river with their headlights pointed towards the shore.

In 1860, the Ottawa Citizen quoted a local doctor as saying that “skating cannot be too highly extolled as an amusement,” adding it “virtually imparts new life to the nervous system, derived from the pure and bracing atmosphere, which is highly charged with oxygen and electricity.” Meanwhile, a British magazine called skating “the nearest approach to flying of which the human being is as yet capable.”

The popularity of skating led to advances in skate and ice technologies, and to the emergence of skating and ice-based sports, most notably hockey, cricket on ice and speed skating. But such sports were initially considered “unworthy of a true skater’s attention,” and it was the ruin of leisurely skating parties when a hockey game would break out.

The many tragedies of thin ice led to a push for the establishment of local rinks, covered rinks and even enclosed rinks. Ottawa actually saw its first arena, the “Ottawa Skating and Curling Club,” open in 1865 on Slater Street (on what is today Confederation Park).

In the late 1800s, the winters would have been cold, harsh and isolating. Richmond Road was a maintained toll road, but people lived mostly without any services — no piped water or sewers, no snow removal, no public recreation facilities.

But the winters would bring residents down to the banks of the Ottawa River where skating could be enjoyed, particularly inside the log booms, or on frozen ponds on former farms.

Later, the odd local rink in a growing neighbourhood would be established by a local entrepreneur, or community-minded volunteer, with access to water pumped from a well. Some early 20th century attempts included a rink at Bethany Presbyterian Church at Parkdale and Gladstone (now Parkdale United Church), a rink run by Jonas Bullman on his property (where 31 Sherbrooke Ave. stands today) and one run by the local Boys Club at Wellington and Hamilton.

Westboro-way, there was a rink at a prime location on Richmond Road just west of Churchill Avenue (about where The Works stands today), that was operated by Patrick Mears for several years pre-WWI. Mears came close to securing support for the construction of an enclosed arena in 1913, but the $8,000 cost was just too high. Westboro instead had to wait 46 years for Lions Park Arena.

Of course, skating and hockey weren’t the only winter recreation options. Snowshoeing and sleigh driving had always been traditional favourites in Canada. Skiing was a favourite for some (who used staves from wood barrels as skis to glide down the canal), but this sport would find its popularity after the arrival of cars which made it easier to travel to the mountains. The Ottawa Ski Club was formed in 1910 largely after an influx of Scandinavian immigrants to the city.

Children of all eras have enjoyed hill sliding. In the 1870s, a favourite activity for the settler Hintonburg kids was to climb Somerset Street hill to the top at Booth Street, and slide all the way down to where the bridge now starts. Cars and streetcars were a worry that was many years away.

Another fad of the early 20th century was tobogganing, and for one magical year in 1914, Westboro was the place to be. A massive toboggan slide was built as a private enterprise by residents David Latimer and J.A. Leech. A 1,000 ft. run built on trestles off the cliff behind Churchill School shot children and adults, who purchased a day or season pass, down a huge slide that took the route of today’s Lower Byron Avenue. The initiative lost money and did not return in 1915.

But the toboggan craze was real, and kids across the city were sliding on whatever makeshift material they could find, down any hill or (dangerously) any street. The Civic Playgrounds Committee in 1919, under pressure from the citizenry, established a city-run sledding hill on the south bank of the canal by the Bank Street Bridge. The following year, other locations were added, including one on Parkdale Avenue (at today’s Parkdale Market). City workers would arrive in December and construct the “slides,” which would provide endless winter fun. Unfortunately, the Parkdale slide lasted only until 1924, when the city scaled back its efforts, apparently due to large numbers of kids picking up skiing instead.

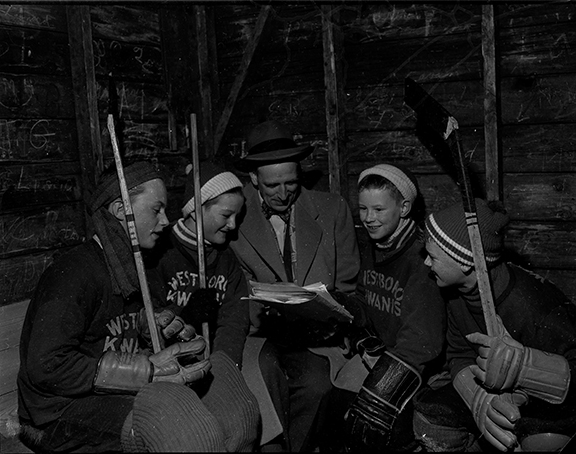

Professional sports caught on in the 1920s and organized sports fell in behind. When the depression hit in 1929, the local playground leagues allowed kids and adults alike to escape their difficult lives briefly with competitive sports. The city established and maintained local rinks, keeping them in particularly good condition for hockey.

The west end saw Plouffe Park have a maintained rink beginning in 1918 (which also featured the city’s only speed track beginning in 1924). Wellington Village’s new park, Fisher Park, started life in 1920 as a skating rink, but in December of 1926 became the city’s sixth official outdoor hockey rink. The Playgrounds Hockey League was very organized, with multiple age divisions, and was very competitive, with strict rules about age and residency (preseason weigh-ins were even required). Teams representing Fisher Park were formed and travelled to other rinks across the city. That same month, Laroche Park saw its first city-run skating rink open.

Over time, new rinks would be added at other Kitchissippi locales such as McKellar Park (1951); Dovercourt (1950); Iona Park (1980); Elmgrove Park (1946); Champlain Park (1927, though not civic-run until 1945); Fairmont Park (1947); and Ev Tremblay Park (1971, named for the founder of the popular old Ottawa Cradle Hockey League).

When the city began building enclosed arenas, the organized playground leagues disappeared, and the maintenance of local rinks fell to residents.

The highlight feature each year for all of the parks was, and continues to be (in non-pandemic times, of course), the annual winter carnivals. Fisher Park hosted its first event in February 1922, a “Fancy Dress Carnival” (Champlain Park’s first carnival in 1927 also had the same title), which drew 300 skaters in costume and 500 spectators. At its peak in the 1950s, Fisher Park’s carnival would attract 5,000 people for day-long games and races, featuring a parade of students representing each of the local schools, and a fireworks display in the evening. Old newspaper accounts indicate that the carnivals at all of Kitchissippi’s parks practically drew out the entire neighbourhood for the day.

Though we won’t have carnivals or even outdoor hockey in 2021, a silver lining of the pandemic may be that many Kitchissippi residents have rediscovered more traditional outdoor recreation ideas than they ever imagined, and have discovered they are having just as much fun.