For Jas Karam, growing up surrounded by substance misuse is a core component of their work as a harm reductionist.

“At the end of the day, I only know what I know about harm reduction at the root because of my lived experience using substances. I can find the compassion for other community members who use because I’ve been there,” Karam said. “The ups and the downs, my lived experience is key to the role that I have.”

As a teenager, Karam learned that cleaning equipment, drinking water, and eating reduced some of the undesirable side effects of consumption. Even while inebriated, they prioritized safety and protective measures.

It wasn’t until Karam began working in this sector one year ago that they learned their lifelong catalogue of safer consumption strategies were forms of harm reduction.

Even with the increased harm reduction infrastructure across the country, Karam says so many people remain misinformed about its purposes and benefits. One potential cause, they offered, is a lack of lived experience.

“A lot of people don’t really care about it if they’re not being directly impacted by it. And so to find compassion when it has no effect on you or your family or loved ones, you’re not going to have that connection and you’re not going to have that compassion,” Karam said.

Harm reduction is becoming a growing topic in Ottawa as the Capital deals with an influx of drug-related overdoses and deaths. In 2023, 188 people died in the city after using drugs, according to Ottawa Public Health. Statistics released in November 2024 found that 244 residents lost their lives so far that year due to the epidemic. Numbers for December were not yet readily available. The data is preliminary, though, and can change based on investigations which can take months.

Ottawa Police said they responded to 32 overdose calls in Kitchissippi in 2024, 28 of which required the use of Narcan, an antagonist that is used to reverse the effects of an opioid overdose. That is compared to 32 calls in 2023 and 22 calls in 2022. Neighbouring Somerset ward saw 322 overdose calls last year compared to 252 in 2023 and 115 in 2022. In 2024, Narcan had to be distributed 246 times.

While the trends are going up, they are nothing in comparison to Rideau-Vanier which had police respond to 849 overdose calls in 2024, more than any other ward.

Individualized, multi-faceted care plans required, say experts

When it comes to drug addiction, many think harm reduction models only enable consumption. Studies from across the world have found that the broad approach is tantamount to maintaining health and well-being during an individual’s recovery.

Physicians at most substance use health organizations like Safer Supply Ottawa do exactly that. This often involves connecting patients with housing agencies, legal aid, food banks, and mental health services, on top of providing physical care like STBBI testing and much more.

According to Rob Boyd from Inner City Health, addiction recovery is a years-long endeavour and relapses are to be expected. With a harm reduction model and adequate support systems, though, individuals are more empowered to continue striving to make healthier choices and continue their path to recovery after a relapse.

“We have to make sure people have access to naloxone, safer ways to consume their drugs, and we have to be realistic sometimes about what our ultimate goal is going to be,” said Boyd.

For many patients, there are simply too many barriers to ever fully abstain from drugs, he added.

“But that doesn’t mean there’s not a lot we can do between where their life is today – between chaotic kinds of use and overdose, to more stable use, housing, harm reduction care, family. All of these things make their lives better but also make them better in the community.”

This remains true with any treatment model. Since substance use health differs from person to person, a ‘one size fits all’ approach or outcome simply will not work.

That’s why Nicholas Boyce from the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition says abstinence is an ineffective recovery marker.

“There are an awful lot of people I’ve met that do end up reducing their drug use, do end up stopping their drug use, and there’s a lot of people who don’t and will always use drugs,” he said. “If the metric you’re using is that people no longer use drugs, if that is your only metric, maybe you would think it’s not doing anything to benefit people.”

The overarching benefit of the safer supply of drugs is that people no longer have to worry about where and how they might acquire their drugs.

“When you give them a pill that might cost a dollar,” Boyce said, “they don’t have to spend their lives running around thinking about drugs. They can actually start to focus on their health and reconnecting with family and jobs. There are immediate health and psychological benefits to the people who are getting those drugs.”

Healthcare is a political matter

Boyce, a Mechanicsville resident, says the province has continually ignored the evidence regarding harm reduction methods, including its own internal reports saying to expand the sites.

“All the evidence shows that it makes communities safer, it saves people’s lives, it gets people connected to care and it’s a cheaper way of doing things,” Boyce said.

That’s why Health Canada allocates a portion of its budget to the Substance Use and Addictions Project each year. Community organizations across the country can apply for time-limited funding for one of their projects. Once the funding for one to five years dries up, organizations have to find alternative funding to maintain them.

Some of the Ottawa-based programs include the Safer Supply program, Centretown Community Health Centre’s outreach program for individuals who use toxic street drugs in downtown Ottawa, and CAPSA’s efforts to decrease stigma in organizations that serve people who use substances.

Due to the substantial overlap of social issues, exacerbation of the housing crisis, crime, and the transmission of STBBIs are likely consequences of harm reduction rollback.

Boyce says the pullback on harm reduction services will spark an influx in HIV and Hepatitis C cases which might backtrack Ontario’s HIV Action Plan to 2030.

“Those people aren’t going to magically just stop using drugs overnight. They’re going to have no access to supplies anymore. We’re just asking for HIV and Hep C to come roaring back.”

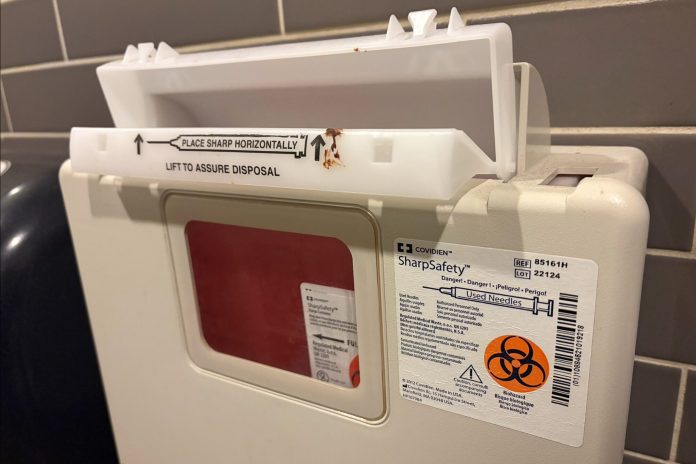

These blood-borne infections are most commonly transmitted through shared needles. Needle exchange programs like the one currently offered at Somerset West Community Health Centre keep blood-borne infections at bay because they ensure community members aren’t picking up used needles and that people who inject substances aren’t reusing needles.

Currently, 11 per cent of people living with HIV are unaware of their diagnosis. Ontario’s action plan outlines how more accessible testing and education are imperative to ensuring the 11 per cent receive treatment and live long lives.