One of Kitchissippi’s most important intersections is nearing 100 years in age, and its future is unclear as a battle between developer and community design plan goes into what may be its final round.

The OMB will be considering allowing the construction of a 12-storey tower – which contravenes the CDP – by way of a loophole offered if the developer (Mizrahi) creates a “landmark” building at the corner of Island Park Drive and Wellington/Richmond. The term “gateway” is being used to describe this dividing point between Westboro and Wellington Village, and in the coming weeks, it will be decided whether this condo building will become its new focal point.

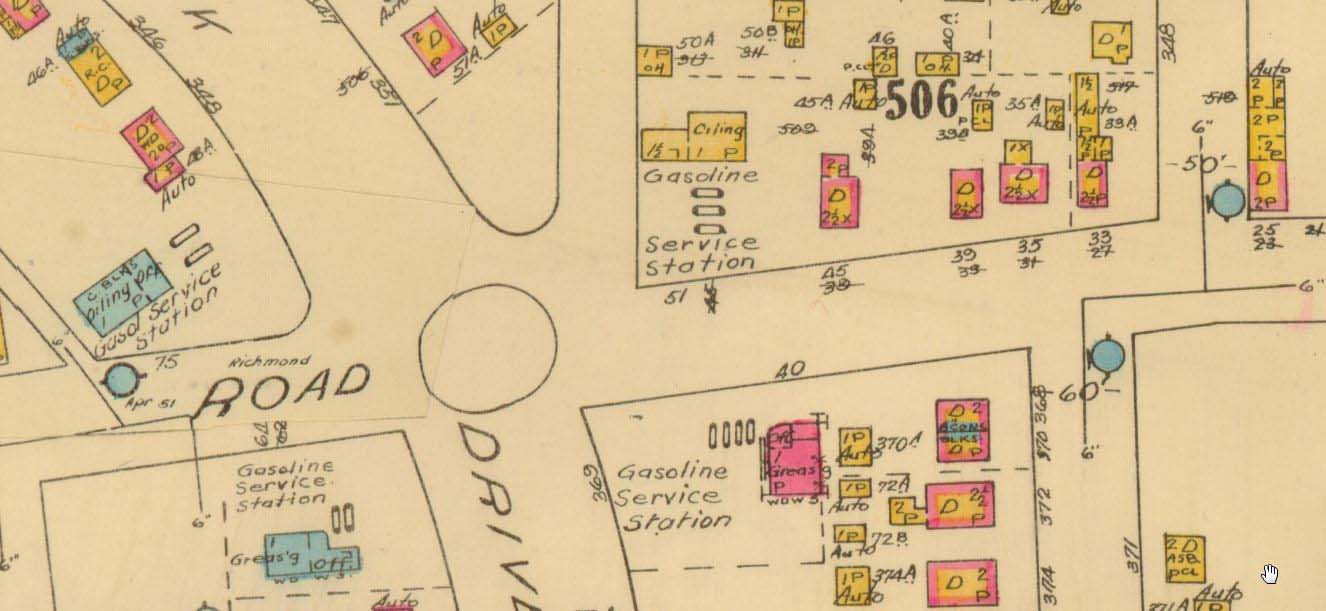

A lot of history exists here, and while some of this corner has become a bit of an eyesore, it wasn’t always this way. John Newcombe has done excellent work in preserving his Esso station on the southeast corner which dates back to 1938. Through the efforts of artist and historian Andrew King and others, Ottawa’s oldest gas station structure, the 1934-built “cottage” on the southwest corner has recently been saved. But the northeast corner is perhaps the most historic, and worthy of exploring.

In 1893, Robert Cowley created a new subdivision “Ottawa West” on his family’s farm, years before most development had begun west of Parkdale. Ottawa West was a small plan situated between Richmond and Scott, bordered by Western and Rockhurst.

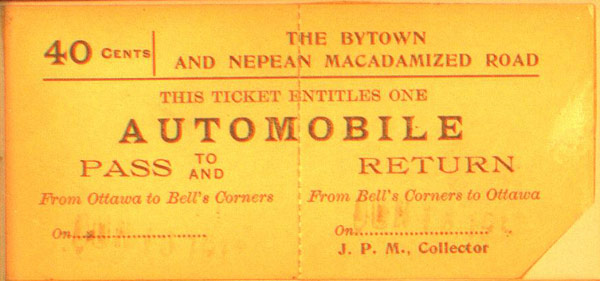

One of the first structures to be built in the subdivision was actually a toll house. Richmond Road from 1853 until 1920 was a toll road operated by the Bytown and Nepean Road Company, and those travelling west from the city limits of Ottawa into Nepean Township were required to pay in order to use it. Up until 1895, the eastern toll house was situated within Hintonburg (the western toll house was in Bells Corners). The Company purchased a lot at the western edge of Cowley’s subdivision (there was no intersection at the time; Island Park Drive was still 28 years away), and constructed a modest house for the tollgate keeper, who operated the gate at all times. A small office was constructed in front of the house, extending onto the roadway, and a large bar stretched across Richmond Road to ensure travellers would stop and pay the required toll, which would vary depending on the time of year, the number of horses, and whether the driver was on horseback or in a carriage.

Many injuries were suffered when tollgate keepers forgot to raise the bar at night. Fast-moving riders (and their horses) would run headfirst into the heavy bar.

By 1920, automobiles became prevalent, private road ownership was being eliminated, and the Road Company could no longer keep up with the road maintenance required (road conditions had become extremely poor during the Company’s final days). Thus the road was sold to municipal government. The toll house remained for a few years as a home. Adjoining it was the new Island Park Driveway, which opened for traffic in 1923; and to the east another house, which had been built by the toll keeper in 1910.

Both houses remained standing until 1929, when the lots were sold to the Cities Service Oil Company. Cities demolished the homes and constructed a gas station to service the growing Wellington Village community and popular Driveway route. This original gas station was a 1 1/2 storey wood-framed structure set back from Wellington Street parallel to the road. It was replaced in the mid-1950s with the diagonally-angled shop that exists today (the office portion was added on in 1973).

By the 1940s, the intersection actually featured gas stations operating on all four corners.

In 1964, BP purchased the station, and kept it in operation until 1973, when it was purchased by Frisby Tire. Frisby lasted for just less than a year. Joe’s Car Radio Sales Ltd. purchased the building in 1974, removed the gas pumps and tanks in 1975, and remained in business for over 30 years. In 2007, Benny and his successful Proshine Car Wash business became the old station’s final occupant.

Just as significantly, the proud old brick home next door has stood the test of time. Built in 1896, Bella’s Bistro is Wellington Street’s oldest surviving building in Wellington Village (and one of the three oldest houses built in the Ottawa West subdivision still standing). It was built by Joseph O’Neil, a 34-year-old millwright for his wife Mary Ann, their seven children (including two sets of twins), his brother and sister-in-law, and their two children.

Joseph O’Neil (who also built the old stone house on Churchill, now the office of law firm Farber-Robillard-Leith) died of appendicitis just seven years later while helping build a sawmill near Parry Sound. His widow Mary Ann remained in the home and raised her children by being very resourceful and taking whatever jobs she could. In the evenings she cleaned offices on Parliament Hill and took in sewing and washing at home during the day. Apparently she even helped take tolls at the toll house next door when the gatekeeper inevitably required a short break. She died in 1953 at the age of 91, after a full and eventful life.

When it was first built, the house was 2 1/2-storeys and 10 rooms. The brickwork which remains today is original. A long workshed was attached at the rear, and at the back of the property was a chicken coop (these additions were replaced during the 1930s). The house was made into a duplex around this time by Mary Ann’s son Clarence, who remained in the home for almost his entire life.

The O’Neil’s granddaughter, Heather Backs, who kindly provided stories about her family for this column, including the great photograph from the 1920s, has wonderful memories of the home. She and other family members still visit on occasion, and she remarks how little the interior has changed over time.

In 1982, the house was converted to a French restaurant, Chez Soi, which later became Pasquale’s in 1987 (operated by Pasquale Valente, patriarch of the family that now operates the popular Fratelli’s restaurants). It became Bella’s Bistro Italiano in the mid-1990s.

Sadly, this beautiful 120-year old building – a house that has seen the neighbourhood grow from vast open farmland to the busy and bustling community that it is today – is doomed to become a victim of the development of Wellington Street. The O’Neil family home is a symbol of the Richmond Road of long ago; of farmers delivering their produce to the city each morning; of Ottawa’s first cars travelling along a dusty, bumpy road; and of a neighbourhood born almost overnight in the excitement and optimism after each of the world wars. The street has transformed from a boulevard of villas and grand homes in the countryside, to a lively commercial street where even this house had to acquiesce and become a restaurant to survive. Indeed it has thrived, from the days when it truly was the gateway entrance to Ottawa, and exists as a true landmark building, one destined to be razed to make way for a “landmark” that will only be artificial in comparison.

Dave Allston is a local history buff who researches and writes house histories and also publishes a popular blog called The Kitchissippi Museum. His family has lived in Kitchissippi for six generations. Do you have any early memories to share? We’d love to hear them! Send your email to stories@kitchissippi.com.