Beechwood Cemetery is a picturesque cemetery that, for the past 148 years, has existed as the final resting place for over 82,000 Canadians. It is Canada’s national cemetery, Canada’s National Military Cemetery and was designated as a national historic site in 2001.

But did you know that Beechwood Cemetery originally came within a whisker of being established in Westboro instead? It’s true!

Westboro (then just known as “Thomson’s farm”) was chosen in 1872 as the location for the new cemetery, and, if not for a strong, last-minute public outcry about its inaccessibility from the city, our neighbourhood would have a completely different history.

The story begins back in January 1872, when smallpox was a constant, serious threat. City council passed a bylaw setting new regulations to control the spread of the deadly disease, including banning the burial of any human remains within the city limits as of Dec. 31. This even included the existing cemeteries in Sandy Hill. A new burial ground was required, and the old cemeteries were to be relocated (Macdonald Park today sits atop where many 19th century Ottawa residents still remain).

At the time, the churches were responsible for managing cemeteries. The Catholic churches of Ottawa acquired land right away on Montreal Road for their new cemetery (Notre Dame), and began to exhume and move bodies by mid-June of 1872. One gory story from the era told of the accidental opening of an old casket to discover a body that had clearly been buried alive.

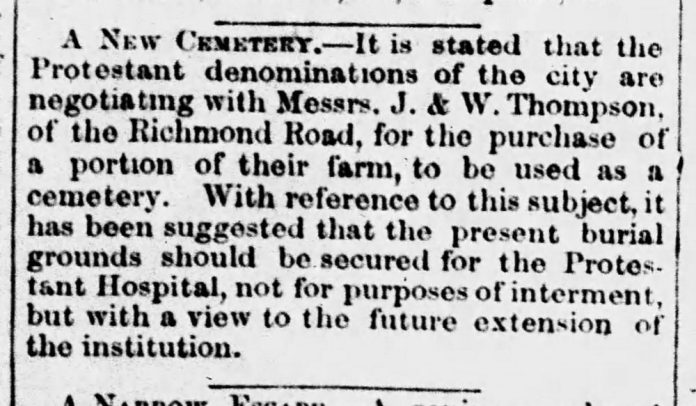

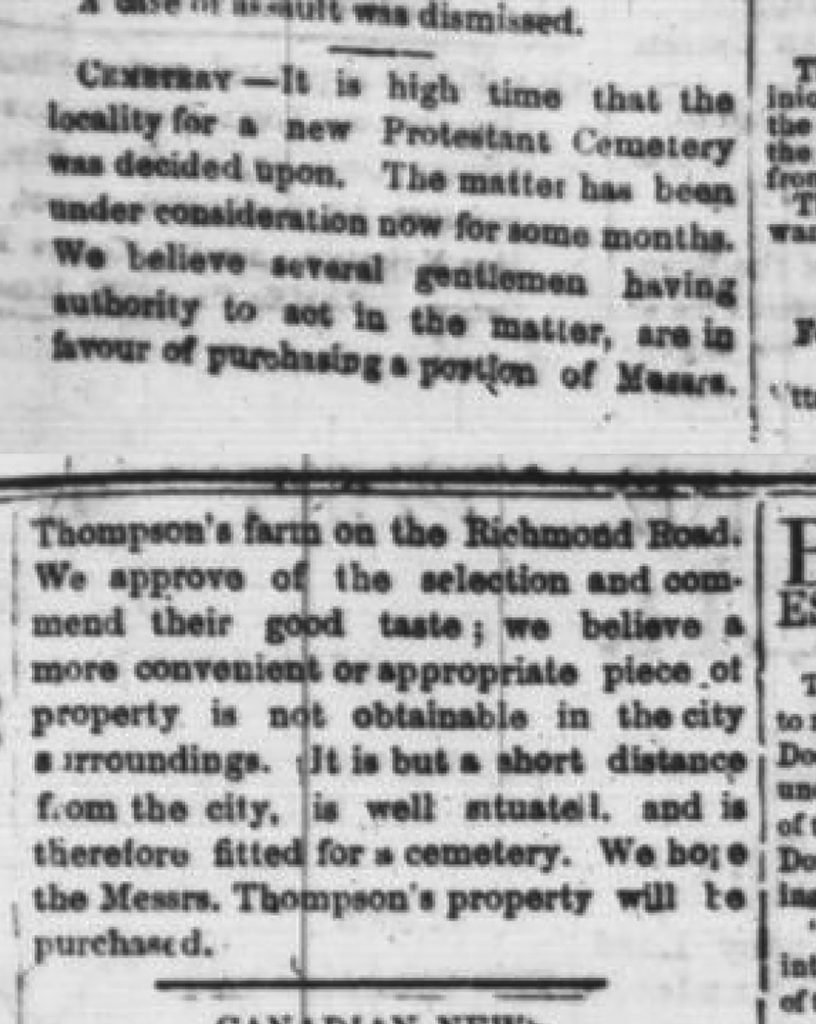

The Protestant churches of Ottawa took much longer to make their decision. A Cemetery Committee was formed and an extensive search conducted. On April 22, 1872, the committee announced that the Thomson farm on Richmond Road (which is today’s Churchill to Fraser Avenue in Westboro) had been selected, and negotiations had begun towards its purchase.

The Thomsons were among the west end’s first settlers, arriving in 1818. They established one of Carleton County’s top farms, and built the gorgeous Maplelawn house (Keg Manor). But by the 1870s, financial difficulties led the family to begin offering portions of the farm for sale.

At the time, the farm was isolated. The area had a handful of houses by the river for workers at Skead’s Mills, a few shops, a small school and All Saints Church on Richmond Road. It was a far distance from the city center, an estimated six miles from the eastern boundary of the city.

When news of the proposed cemetery location initially broke, there was some public outcry, but the decision appeared to be all but final through the summer and early fall of 1872. Arrangements had even been made with the manager of the Canada Central Railway (which took the route of the Parkway through Westboro) to establish a station at the cemetery and run funeral trains for $10 round trip (argued as being far cheaper than hiring a series of carriages and cabs from the city).

By mid-October, the deadline for burials within the city was drawing near (it would later be extended by a year), and the Thomson farm purchase had not been made. It appears the committee, largely made up of representatives of the “Upper Town” congregations (the western part of the city), was trying to quietly push through the Thomson farm purchase.

Public attention was called to the pending purchase, with accusations of deception, and even speculation implications, levied against the committee members.

For much of October, the topic raged in the local papers and amongst the citizenry of Ottawa.

By chance, the late-October meeting of Protestant congregations, where the Thomson farm purchase would be ratified, was poorly attended, and the chair decided to put off the formal approval for a week.

As the Protestant congregation leaders discussed their options internally, residents of the city voiced their opinions through the two city newspapers, and to their churches. Naturally, those living in the east end were not at all in favour of a site way out at Richmond Road.

The Ottawa Citizen agreed that the Thomson farm was too far out, and instead suggested the Hinton farm (today’s Hintonburg) or the Williams Farm (today’s Old Ottawa South). The Ottawa Times, meanwhile, supported the Thomson farm selection, arguing that citizens should be “gratified” to have the cemetery at a “respectable distance from them,” as “a person does not drive to the graveyard in or after a hearse every day.”

Though it was argued that the soil and property was ideal for cemetery purposes, there was little else positive about the Thomson farm. It was expensive (offered at $150/ac), relatively wide-open, exposed to cold north and west winds and subject to snow blown from the river, and far from the city. Furthermore, it was noted by medical officials that not only would the wind from the cemetery prove harmful to the city, but drainage from the area flowed naturally into the river, just upstream from where the new water works system was to draw the city water supply. On top of this, the moving of the dead from the existing cemetery in Sandy Hill would have meant transporting the exhumed bodies a great distance through the city.

Interestingly, the committee had initially preferred the Bayne Farm (today’s Civic Hospital area) for the cemetery, and though at the time there were 75 open acres available, Bayne was only willing to sell 15 of them. The committee also took interest in the Cowley farm (today’s Hampton-Iona area) while travelling past to look at Thomson’s farm, but it was even more expensive ($175/ac).

The most poignant argument made was the need to have the cemetery situated “within easy reach of the poorest among us.” It was agreed that if the cemetery was placed out in future-Westboro, it would simply be inaccessible for a large segment of the population.

The debate within the Protestant churches raged, with the argument threatening to divide the 11 churches, not only to have two cemeteries, but tear apart the Ottawa congregations entirely.

By mid-November, the Protestants had narrowed the conversation down to two options: the Thomson farm and the McPhail farm near New Edinburgh.

The McPhail farm had many advantages, including cost (just $80/ac) and proximity to the new Notre Dame Cemetery. It was also more scenic and it contained 30 acres of “finely timbered land” — that alone was worth $4,000. Most importantly, it was far more convenient to the city.

The Protestant leaders agreed that a decision needed to be made “harmoniously and unanimously.” Several congregations, which originally supported the Westboro location, felt more concerned about the division amongst the Protestants, and thus were willing to change their votes to support the majority.

The McPhail farm purchase was approved on Nov. 12, 1872. At the Protestant meeting the week after, Rev. Pollard suggested the cemetery be known and designated as “Beechwood Cemetery” (which was accepted by a vote, over the alternate name of “Rockliffe”). An Act was drawn up for the company, which stated that single graves would cost no more than $5 ($2.50 for children), and that Beechwood would be non-sectarian, open to all.

Immediately, the selection of the McPhail property was applauded for its “secluded position…its beautiful shrubbery and heavy wooded covering, together with its romantic appearance, render the selection more pleasing than any other within a reasonable distance of the city,” so stated a writer to the Ottawa Citizen.

The new cemeteries were a vast improvement on the old Sandy Hill cemeteries, which the Ottawa Citizen called “exceedingly repulsive.” It was integral for Canada’s capital city to have an impressive resting place, for Beechwood to be “a place of resort for all classes of our citizens – where they and their children and friends, dead and living, may meet amid the most beautiful gifts of nature. God’s Acre should be made as lovely as any park or garden – not a glaring, repulsive aggregation of stones and palings. Nature has given us in ‘Beechwood’ nearly all the attributes of a Mount Auburn. It is for us to go on and do the rest with taste and judgment.” The first interments would occur on Aug. 21, 1873.

The loss of the cemetery sale must have deflated the Thomsons. Despite attempts to sell lots and parcel-sized pieces of their farm, they found little interest in their remote real estate. Within just a couple of years, they defaulted on their mortgage, and lost the farm to foreclosure, ending their significant 60-year presence on Richmond Road. Though we still have Maplelawn to remember them by, it is incredible to consider the area between Churchill and Fraser might today instead be the home of Beechwood Cemetery! It truly nearly was!