Every December, Kitchissippi transforms into a glittering tapestry of holiday cheer.

From classic evergreens decked in red and gold to modern marvels like laser shows, pre-lit artificial trees, and 3D characters, the neighbourhood sparkles with the season’s joy. Each fall, stores unveil new innovations: LED lights that shimmer in impossible patterns, solar-powered decorations, and trees that glow in every imaginable colour. But behind the sparkle lies a story that stretches back more than two centuries—a story of technology, tradition, and the occasional fire hazard.

It’s almost unimaginable now that there was a time when families brought home real pine trees, placing them in tubs or sand-filled boxes, and illuminating them with tiny wax candles. In 19th-century North America, the holiday season could be as perilous as it was festive. Newspapers frequently reported fires caused by Christmas trees.

Dried-out pines ignited easily, and the wood-frame homes of the era offered little resistance. One notorious incident in 1885 saw a Chicago hospital fire, started by candles on a massive tree, injuring over one hundred people, mostly children.

Ottawa and Kitchissippi were not immune. Firemen were often hired to attend midnight mass on Christmas Eve at Catholic churches, standing ready in case of disaster.

Fire Chiefs would make annual pleas to the public for caution in its use of candles and flammable decorations, and to not place trees near window curtains where draughts could blow draperies on to lights. Many decorations were even made of tissue paper, cotton and even dangerous celluloid. It was even recommended that Santa Claus costumes be dipped in a solution of phosphate of ammonia and water, as Santa would be in close proximity to the tree branches, pulling gifts and talking to children.

“A house of merriment is better than a house of mourning” trumpeted one early campaign.

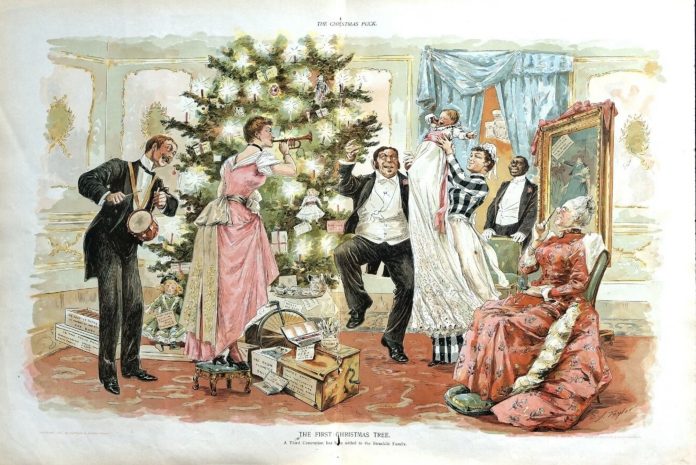

In those early days, Christmas trees were often petite, tabletop versions. Candles were nestled among the branches, sometimes hidden behind paper decorations.

Strings of popcorn and cranberries wound their way around the tree, while small gifts—boxes of candy, nuts, sweetmeats, and oranges—were tucked into the foliage rather than left beneath. Some trees were rigged to revolve, creating a mini spectacle of light and shadow. When the candles burned out, children would rush the tree to collect their presents. Trees were often perched in sand-filled tubs or boxes, occasionally draped with green felt for a touch of festive decor.

The rise of electricity in the late 19th century brought the first major innovations to the Christmas tree. The tradition of cutting trees for decoration had gained traction in North America during the 1860s and 1870s, tracing its roots to 16th-century Germany. By the early 1880s, towering trees—sometimes 30 feet tall—appeared in churches and schools, while smaller trees sold in grocery stores for fifty cents to a few dollars. Critics sometimes decried the wastefulness of cutting down trees for decoration, though supporters argued that the joy of children was worth the small cost.

Entrepreneurs were quick to experiment with artificial trees—safer, reusable, and perfect for embracing new technology. In 1878, the first patent for an artificial tree was filed in New York City. John George Wolf’s design pumped gas through the tree’s stem to small burners on ten branches, intended for shop windows and homes alike. The gas tree never caught on, but by 1882, a company in Troy, New York, was producing artificial Christmas trees,

That same year, electric lights made their first appearance on a Christmas tree. Thomas Edison had only recently perfected a practical bulb, and Edward Johnson, vice president of the Edison Electric Light Company, lit his tree in New York City with 80 red, white, and blue bulbs, attracting crowds to his front window. Wealthy households followed suit, though each bulb required an expensive electrician to wire it—and remain on call for emergencies. The trend reached the national stage when U.S. President Grover Cleveland installed the first electrically lit tree in the White House in 1895.

Ottawa embraced the new technology quickly. The city’s first known electric tree appeared in 1898 at the Anglesea Square Anglican Mission Hall, delighting over 100 children. But the use of electricity in holiday displays predated that: in 1891, St. Patrick’s Church on Kent Street arranged electric lights in the shape of an asterisk, symbolizing the Star of Bethlehem. By 1894, the church had decorated its altar with 300 lights for midnight mass.

Businesses also seized on the possibilities of electric lighting. In 1895, Olmsted and Hurdman on Sparks Street boasted “judicious arrangements of electric lights” inside their store, and Bryson, Graham Ltd. reportedly hung a row of colored bulbs along their building in 1909. Community trees began to emerge, too. In 1918, the Rotary Club erected a massive tree on the Plaza between the Chateau Laurier and Union Station. It contained “chains of little electric lights threaded through its branches” and “surmounted by a large electrically-lighted star”.

Santa himself took advantage of the technological advances, and starting in 1896 began touring the city on Christmas Eve, distributing thousands of oranges to children, in what was to become the first ever Ottawa Christmas parade. The parade reached as far west as near Preston and Albert Streets, where the streetcar looped into LeBreton Flats. Two years later, in 1898, Christmas lights were used to decorate Santa’s streetcar, “312 tiny lamps, giving it the appearance of a moving ball of fire”, reported the Citizen.

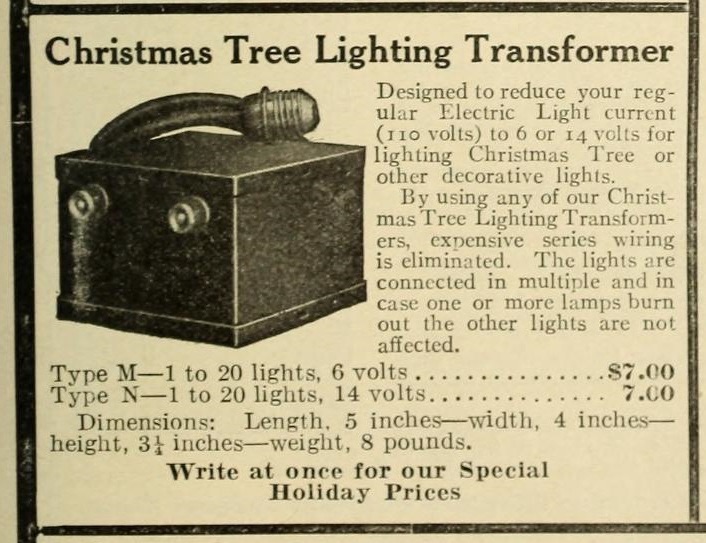

Not surprisingly, Ahearn & Soper, founders of the Ottawa Electric Railway, were the first to advertise electric Christmas tree decorations in Ottawa, promoting “miniature electric lamps for window and Christmas tree” in 1903.

There were also sold at the time, “fireproof sparklers” which could be “twisted on the branches without trouble and can be replenished many times a day”. (Though they turned out to be not quite so fireproof).

The electrification of Christmas even prompted Popular Electricity magazine to run a poem on the topic on the back cover of its November 1908 issue.

During WWI, six major manufacturers came to an agreement to standardize wall plug designs, and thus the widespread use of the two-pronged plug came soon after. Older homes installed these simple wall sockets, while all new homes of the 1920s would have them. This enabled mass production of easy-plug light sets, and other electric decorations, which were increasingly affordable. Electric tree light sets were available under $2 in shops in Ottawa and the west end by 1925, and less than a dollar by 1931.

Christmas tree lights and electric decorations exploded in popularity during this period, and continued to grow particularly after WWII.

Artificial trees, however, remained uncommon until wartime restrictions encouraged their adoption. During WWII, Ontario limited the transport of live trees, prompting predictions that artificial trees would outnumber real ones for Christmas 1943. After the war, convenience kept artificial trees in many homes, even as Canada’s tree industry thrived. By 1946, the country exported 18 million trees, valued at $1.3 million—equivalent to $22 million today.

Meanwhile, companies such as NOMA (originally the National Outfit Manufacturers Association) pioneered innovations in holiday lighting. Interconnectable strings, rubber cords, and the iconic Bubble Lites transformed both indoor and outdoor displays. Other decorations evolved too: tinsel shifted from hazardous lead foil to safe plastic, ornaments became more durable, Christmas villages gained popularity in the 1970s, and LEDs enabled intricate automated displays.

Through all these changes, tradition persisted. Many families still delight in cutting down a fresh tree or arranging handmade ornaments, yet the embrace of new technology has long been part of the Christmas spirit—a holiday trait that, as history shows, is nearly as old as the celebration itself.