McCormick Park is a quirky little park in the heart of Hintonburg that boasts trees, benches, a playground and covered seating. It’s a meeting place for local residents. And likewise, McCormick Street is a quirky little street that surely must hold the record in Ottawa for being the thinnest two-way street with parking allowed.

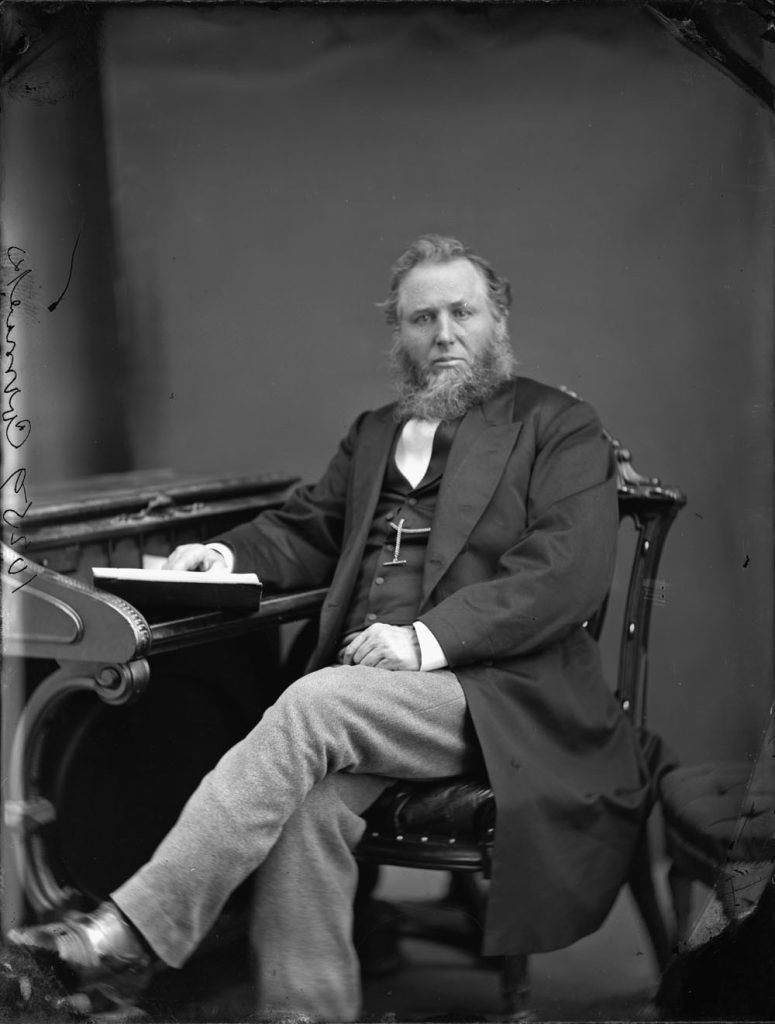

Henry McCormick was born on Eden Island, Ireland, in 1818, and came to Canada with his parents and young siblings sometime in the mid-to-late 1820s. Before long, the McCormick family had found themselves in what was then just the small settlement of Bytown amidst construction of the Rideau Canal. His father, Alex McCormick, was a general labourer who may have helped build the canal, and Henry would have been as young as 10 years of age on arriving in the primitive village.

Henry McCormick grew up alongside Bytown. He took an interest in baking, and by his early 20s, was operating a successful bakery in Lowertown on Dalhousie Street, commencing sometime in the early 1840s. In fact, his bakery at 210 Dalhousie Street remains preserved today as one of Ottawa’s most important heritage structures as well as one of its first commercial stone buildings.

According to a profile in the Lowertown Echo: “The bakery specialized in shanty biscuits that were long lasting and could be carried into the woods with the workers. It also delivered bread using two-wheeled carts that could navigate the muddy streets.”

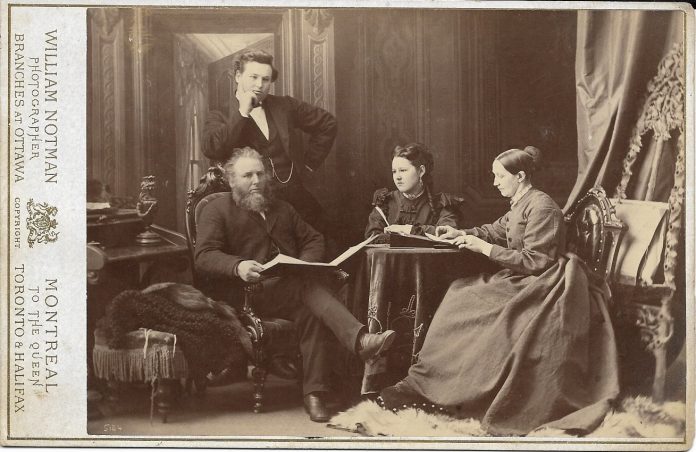

Henry married Eliza Jane Best in 1845, with whom he had two children, Alex (1848) and Letitia (1850). He occasionally hired his brother-in-law Francis Best to operate his thriving bakery for him, particularly after he opened a flour mill in the late 1850s. For a time, Henry also operated a tavern.

Henry was a witness to Bytown’s growth, and was present at the Stony Monday Riot, which took place on September 17, 1949, giving testimony at the ensuing trial.

He also took an interest in the development of Bytown, lobbying Town Council for a plank side walk on Dalhousie Street in 1851 (he lost). But a few months later, a bylaw indicates that Henry himself was paid 282 pounds for “making improvements on the streets of Bytown.”

He also operated a flour, feed and grain business on Sparks Street for over 30 years, and was located in the building next door to where D’Arcy McGee was assassinated in April 1868.

In the early 1860s, he opened a new bakery on the corner of Queen and O’Connor, where he was producing “forty to fifty barrels of loaf-bread baked weekly, and two waggons [sic] employed constantly” to deliver it.

When McCormick listed his bakery for sale in 1865, he advertised it as a “potential government bakery,” as the public service had begun to expand in Ottawa, and the holding of Parliament here was to begin the following year.

He seemingly struggled with the idea of having to sell his bakery, but his booming mill business simply required too much of his time.

His mill, called Hull Flour Mills, located – not surprisingly – in Hull, was grinding 70,000 bushels of wheat per year through the 1850s and 1860s.

Throughout this period, Henry was also involved in many other facets of public life. He was an Alderman for Wellington Ward on City Council; an Ensign in the local militia (the Seventh Battalion, Carleton) during the era of the Fenian raids; a school trustee; president of the Building Society; treasurer of the Irish Protestant Benevolent Association; treasurer of a Loyal Orange District Lodge; Chairman of the Temporal Committee of Knox Church; a director of the Ottawa Auxiliary Bible Society; and director at Beechwood Cemetery.

In August of 1872, it was announced that Henry was going into partnership with his 24-year old son Alexander George, and that the firm would become known as H. McCormick & Son.

A tragic event occurred in January 1875 when Henry’s daughter Letitia’s 24-year old husband John James Little passed away in Toronto, leaving Letitia a pregnant widow with two other young children.

Letitia returned to Ottawa to live with her parents, and Henry surely must have felt a larger, more peaceful homestead was needed versus living on an upper floor of a Sparks Street commercial building.

He found it, in a large country villa on a sprawling 4-acre property in a growing settlement that would not be named Hintonburg for another four years.

James Fitzgibbon, an engineer on Colonel By’s staff, had built the first frame house in Bytown. But 40 years later, in 1865, he decided to build a stately home on Richmond Road to spend his retirement years. Sadly, he was only able to enjoy the home for three years before he passed away in December of 1868. His widow Maria remained in the home for a few years, but in 1875, she made the decision to move into the city and rent out her home.

The McCormick family leased it from Maria. Henry and Eliza, Letitia and her three children, and Alex all moved in. This home too still stands today, as the interior portion of the Holy Rosary Church at 1153 Wellington Street West. (Two years later, Letitia purchased the house and property, with 100% of the $2,857 price mortgaged).

They called their home “Maple Villa.”

Over the next few years, Henry and Alex would suffer through some difficult times with the business. Their firm was declared insolvent in August of 1878, and after getting through that, their Hull mill was destroyed by a major fire in November 1882.

But they survived and continued their milling and flour business on Sparks Street.

in June of 1883, the McCormicks acquired 2 additional acres from Fitzgibbon adjoining their house to the east, and brought a new industry to Hintonburg. In the summer of 1885, they opened a “large and capacious” grain elevator (now the site of the RBC bank). The building was 3 ½ stories high, and 40 feet by 40 feet in dimension. The bottom storey was built of stone and the others of heavy timber faced with brick. The machinery was driven by a twelve horse-power engine.

Grain elevators were typically very tall structures which were used to receive, store and ship large quantities of grain. Storage was important during periods of major market fluctuations, where it was advantageous to store grain until market conditions improved.

The McCormicks became popular with the farmers of the district, as they would purchase their grain directly from Nepean farms.

They also soon erected a large warehouse on Broad Street in LeBreton Flats.

Henry McCormick, now in his late 60s, became involved in bettering Hintonburg as well, serving as a trustee on the early Hintonburg School Board. He also advocated for smaller milling firms at the federal Railway Commission in 1886, arguing that the government should intervene on the issue of some Canadian companies receiving special freight rates over others.

Henry died suddenly at his Richmond Road home on April 6, 1888, of a ruptured blood vessel. The day before, he had seemed in perfect health, conducting business in the city as usual.

Things then changed quickly. Alex moved their offices on Sparks Street to the Broad Street warehouse, but in October of 1889, he announced he was moving to Chicago to work in the lumber business. All of the H. McCormick & Son assets were put up for rent, including the property in Hintonburg.

In December of 1889, Alex and his sister Letitia saw the popularity of land in Hintonburg exploding, so they filed a small subdivision of most of their property (Carleton County Plan 109). The plan laid out 17 new building lots, and created McCormick Street on the eastern edge, and two small streets in behind called 1st Avenue and 2nd Avenue (later simply incorporated as part of Grant Street and Armstrong Street).

On April 22, 1890, a large estate auction was held at Maple Villa with a long list of items for sale, including five bedroom sets, a piano and a buggy express wagon.

That same month, Alex sold the grain elevator on the property to fellow grain dealer Robert Mason. Within two years, Mason would default on the mortgage, and ownership would return to the McCormicks. In 1909, James Forward would acquire the mill, build an enormous hay and feed warehouse addition, and operate a mill here until 1942. The building was repurposed as the West End Tire and Vulcanizing Shop and a Builders Supply warehouse before being demolished between 1956-1957 to make way for a gas station, and later an A&W drive-in.

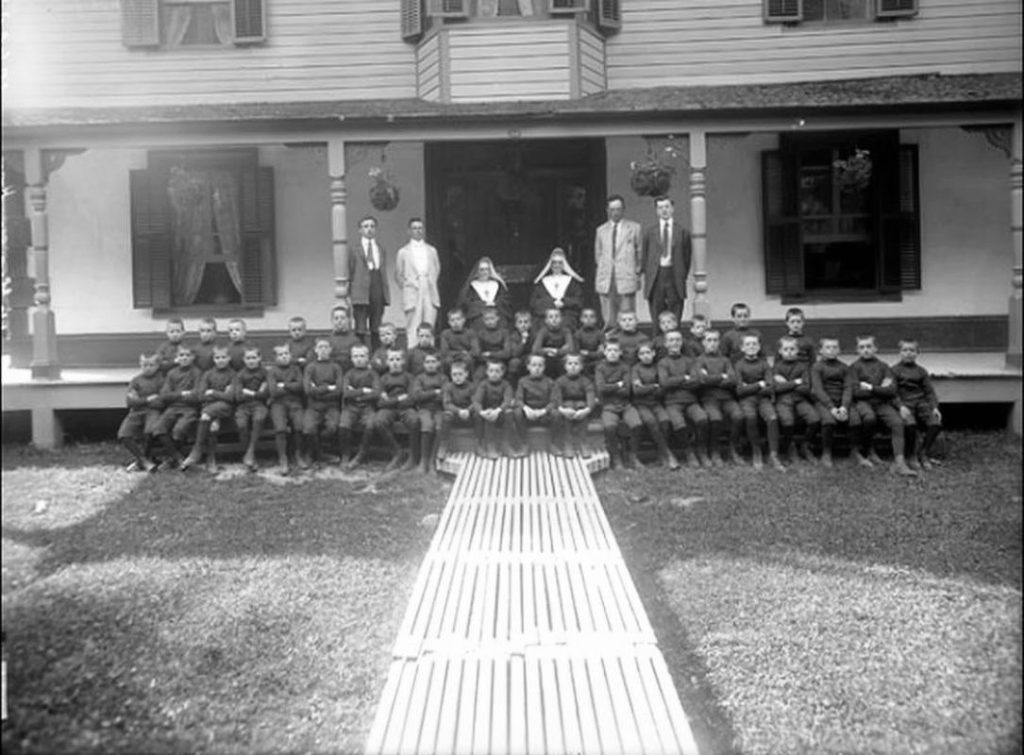

Maple Villa, meanwhile, would be rented out by the McCormicks, with its large lawns, stable and coachhouse, until purchased in 1896 to become a receiving and distributing home for Roman Catholic children immigrating from the UK. Originally known as New Orpington Lodge, it is better remembered as St. George’s Home. The Holy Rosary parish took over in 1947, and retained the old Victorian home within its structure.

Alex McCormick did not last long in Chicago, and returned to Ottawa where he would go on to manage the local branch of the Lake of the Woods Milling Company until his death from a heart attack in 1913.

Although the McCormicks’ time in Hintonburg is in the distant past, it’s fitting that some traces still remain of a man and his family who had front row seats to some of the biggest events in early Ottawa history, and who brought new industry and employment to Hintonburg during its earliest years.