It was 1984, and Ottawa artist Jeff Thomas stood on Queen Street West in Toronto with his son Bear. The curator, activist, and cultural theorist had just moved to the big city with his family. It was a surreal but also isolating experience.

“It was very busy, and I wondered how long we’d need to stand there before we saw another Indigenous person walk by,” said Thomas.

An idea struck. Thomas picked up his camera and began snapping photos of his son. He wanted Bear to grow up with stories and memories, to tell a story.

Decades later, those photographs hang on the walls of the Ottawa Art Gallery (OAG), a free space near the Rideau Centre that promotes creativity and supports local artists. Thomas’ exhibition, “Stories My Father Couldn’t Tell Me, ” runs until March 16 and holds deep and personal meaning.

“It’s a starting point for telling my own story. The stories I wanted from my father were about living in the city as an Indigenous person and living on a reserve,” he said. “It was just things that he wasn’t going to talk about, so I was pretty much left on my own.”

These two parts of Thomas’ life were brought together for the work in his exhibition, “Dream Panels,” which the OAG said is “authorship of his experience on this land, regardless of government designations, in resistance, reflection and activism.”

Ottawa became a place of inspiration

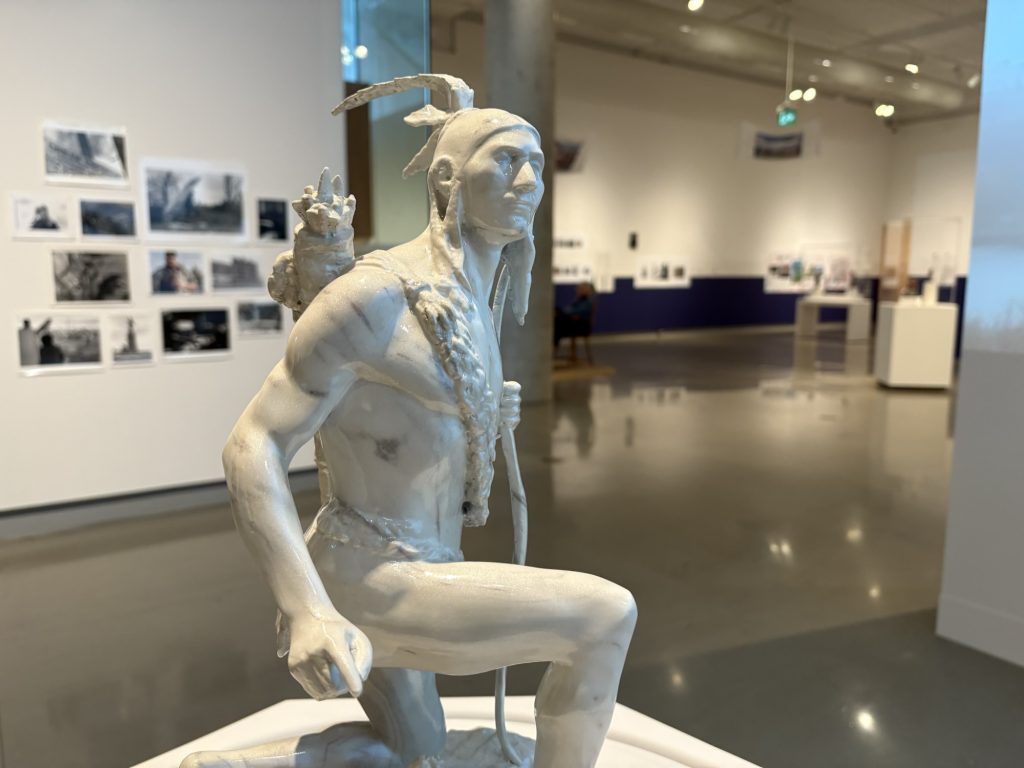

Thomas, whose hometown is Buffalo, New York, first came to Ottawa in 1992 at the suggestion of his then-partner to see the Samuel De Champlain statue on what was then known as Nepean Point. At its base was a life-size Indian figure kneeling. It was nearly invisible.

“We came up there in Remembrance Day week, which set off this whole question of how you make the invisible visible. That was a question I began addressing when I moved to Ottawa in 1993,” said Thomas.

A decade after standing on Queen Street West in Toronto, Thomas was finishing up a contract with Library and Archives Canada, where he was writing new captions for photographs that contained inappropriate words once used to describe Indigenous people. On his final day, he met the then-curator of the Ottawa Art Gallery, who offered him a solo exhibition.

“I had displayed a photograph of what I called the Indian scout in the lobby area. Shortly after my exhibition closed, the assembly of First Nations had their protest at the Champlain monument and asked for the Indian figure to be removed. I was in opposition to that because I felt that it was an important landmark to talk about colonialism and all the other things associated with that,” said Thomas. “That was like my avatar, in a way. I was looking at scouting for him and finding other Indians like him, and so I began a research project at Librarian and Archives Canada.”

That was a challenging project to do, he said. Photos of Indian Residential Schools were in the hands of the Canadian government or the church. They were once used to make the practice which killed thousands of children look beneficial rather than the horrors which occurred.

Thomas sought advice from mentors like architect Douglas Cardinal. The designer of the Canadian Museum of Nature was enrolled at St. Joseph’s Convent Residential School in Red Deer, Alberta.

”I had a firm belief that photographs have the ability to ignite your imagination and to take you to a different place outside of the picture itself,” said Thomas. “I realized that one of the things that I found was so important and missing from the residential school era was the ability to dream. And as an artist, it’s my currency. It’s what inspires my work. And then I thought, well, how do we begin to heal? And I thought, well, about renewing the sense of dreaming.”