By Dave O’Malley and Jamie McLennan

Young men and women who are killed on active service are said to have paid the “supreme sacrifice.” There’s not much more that you can give than your life, but we posit that the greatest sacrifice of all is borne by the families of those killed in the line of duty.

Airmen, soldiers and sailors who die in battle are lionized, and rightly so, but it’s their mothers, fathers, wives and families who are conscripted to carry the burden of that sacrifice to the end of their days. This project is dedicated to those families of Hintonburg, Westboro, Mechanicsville and other neighbourhoods of Kitchissippi Ward that lost a loved one in the great wars of the 20th Century.

The neighbourhoods of Kitchissippi are truly perfect places to start a career, raise a family, build a business and live out a life, but once it must have felt like the saddest place on Earth. Its avenues ran with apprehension and despair, its busy serenity masked the constant high-frequency vibration of anxiety and the low pounding of sorrow. Behind every drawn curtain hid anxious families, broken parents, heartbroken wives, memories of summers past and lost, the promises of futures destroyed and children who would never know their fathers. These were the years of the world wars.

There was nothing particularly special about these neighbourhoods that brought this plague of anguish, nothing that it deserved, nothing that warranted a special attention from death. Indeed, the neighbourhoods of Kitchissippi were not singled out at all — though it may have felt like it was to its citizens. Every community in Canada took the same punishment, felt the endless blows to its heart, felt its life blood seeping away. Parents stood by while their sons and daughters left home, the routines that gave comfort, the futures that beckoned, and began arduous journeys that would lead most to war and great risk of death.

Some would die in training, others in transit. Some of diseases and even murder.

Some in accidents close to home, others would fall from the sky deep in enemy lands. Some by “friendly” fire, others by great malice. Many would simply disappear with no known grave, lost to the sea, a cloud covered mountain, a blinding flash, a trackless jungle. Some would die in an instant, others with prolonged fear and pain. An extraordinarily high number would not come home in one piece.

Though it was not alone in its sorrow, Hintonburg was the first community in Canada and indeed in all Allied countries to feel a blow in the Second World War.

The parents of the very first Allied service person to die in that war lived on Spadina Avenue. Pilot Officer Ellard Cummings was killed just a few hours after war was declared on September 3, 1939, when the Westland Wallace aircraft he was piloting crashed into a mountain in Scotland in heavy fog.

We began to wonder how many other stories there were in these streets and avenues. How many more had been lost? How many families were affected?

What we found out left us speechless.

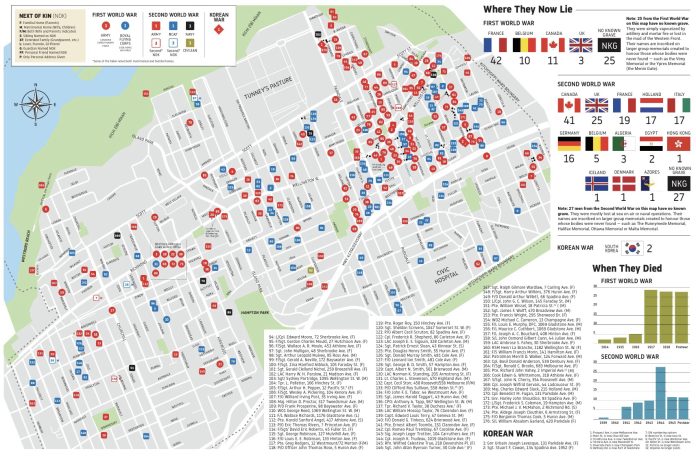

In the age of the “infographic,” we set out to demonstrate visually what that number of fallen meant to each community in Ottawa by mapping deaths footprints. And so began a quest to find and map the homes of the loved ones of the fallen soldiers, airmen and sailors of Kitchissippi – Hintonburg, Ottawa West, Westboro, Mechanicsville, Laurentian View and others – the once young neighbourhoods of a growing city.

In Hintonburg and Westboro, as in most urban neighbourhoods at the time, the Grim Reaper took the form of the telegram boy who had the duty to deliver both good and bad news. Mothers, looking out from their front porches, fathers from their parlours, wives from their washing, must have cringed to see the young man from the Canadian National Telegram and Cable Company pedal or drive down their street, and willed them to move on.

Each pin on the map represents the home of the fallen’s next-of-kin. For the most part, this meant the parental home, the marital home or residence where a wife was living with her parents. In some cases a sibling, grandparent or even a friend was all the soldier could muster as next-of-kin. We used only addresses that were mentioned in casualty lists, service files or as reported in the daily broadsheet newspapers and cross-checked these sources for accuracy.

The 269 men we were able to pin to the map represent only a tiny fraction of the Canadians who died in First and Second World Wars. But among them, we found the complete picture of these wars as it affected this country.

Among the dead of the “Great War” we found men who died on Ypres, Passchendaele, the Somme, the Battles of Hill 70, Amiens, Cambrai, Courcelette and Vimy Ridge. There were men who died in the opening months of the war and men who died in the closing days. Many of the major battles that Canadians were involved in during the Second World War are represented by someone in this group — the Battle of the Atlantic, North African Campaign, Defence of Hong Kong, Dieppe Raid, Battle of Ortona, D-Day and the Normandy Campaign, Battle of the Scheldt Estuary, the never-ending campaigns of Bomber Command, Fighter Command, Coastal Command, Transport Command, and the dangerous activities of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan.

More than 50 of these men simply vanished – vapourized by artillery or their own bomb loads, buried in the mud, lost on some nameless jungle track. Others disappeared into the English Channel, Mediterranean Sea, North Sea, Irish Sea, or the depths of the Atlantic Ocean. Their mothers and fathers would have no answers, no headstone, no closure as we call it today. Simply a name on a wall in a place they will never visit, a picture of a boy in a uniform on the mantle and memories to haunt them until their dying days.

If this map included a pin for every family in Kitchissippi that had a son or daughter at risk during these wars, the underlying streets would not be visible. As it is, it reveals an astonishing toll paid by these families. Families just like yours and ours.

When the Second World War started, many Kitchissippi families were still recovering from “the war to end all wars” — parents still shattered by the loss of their children, veterans coping with the effects of amputations, gas poisoning or “shell shock” — or as we now call it, PTSD. The marks of that trauma were everywhere in Kitchissippi neighbourhoods in 1939 when the worry and pain of a new paroxysm of violence shook it once again.

This map is not about the dead per se. It is a map of the addresses of the next-of-kin of those who died. It is a map of sorrow, a geographic depiction of the carnage on the home front and a way to change the abstraction of remembrance into a visceral understanding of the emotional damage done in Kitchissippi over that 30-year period.

We have made no judgment on the manner of death. If they were on a casualty list or in the Canadian Virtual War Memorial, they were included. The vast majority died in action or on military service.

God bless them.

Jamie McLennan (Character Creative) and Dave O’Malley (Aerographics) are both graphic designers in Ottawa. Each has built a business and raised a family in their respective communities and works to build stronger and more vibrant neighbourhoods through design, place branding, sponsorship, volunteerism and community involvement.