It is hard to imagine that there was once a time when the residents of Kitchissippi genuinely feared an attack by air.

The year 1942 brought great anxiety throughout the world. As the Second World War raged in Europe, North Africa, and Asia, the threat of an attack in Canada grew. Coastal regions — and its government nexus in Ottawa — were seen as likely targets. Munitions plants, dockyards, wharves, railway yards and factories were all high-profile potential bombing threats.

In fact, even well before Pearl Harbour saw the war come to North American soil, the Canadian government had established an air raid response program, so that it would be prepared if it needed to suddenly implement a widespread plan.

This became a highly political topic in Canada. Though civil defense was clearly a federal responsibility, the implementation would have financial and practical responsibilities to be sorted with the provinces. These political decisions would drag on through the early part of the war, and a lack of a cohesive plan meant municipalities were often on their own to solve issues that needed to be dealt with federally.

Much debate was even held as to which department would be responsible for the oversight of Canada’s A.R.P. (Air Raid Precautions) program. It would not be the Defence Department which oversaw this coordination, but rather the Pensions and National Health Department, as it was seen that the effects of the attacks, particularly if gas was used, would be health related.

By 1941, the City of Ottawa was still in a scramble for a master plan. Ontario had initially refused to participate in the federal A.R.P. program, but relented in the fall of 1940. A dedicated division was soon created for the National Capital Region, with first-aid posts set up, and 2,000 wardens recruited to oversee. But the division of responsibility was often unclear.

At the top of the agenda for city officials in Ottawa were roles which could be delegated to residents: blackouts, rapid bomb extinguishing, and construction of air raid shelters.

Once WWII began, in England, shelters were becoming increasingly necessary as Nazi Germany had been bombing London and other strategic points across Britain throughout the fall of 1940 into the spring of 1941. Though high-income earners would pay for their own shelters, the government subsidized citizens within lower income brackets to build a shelter within their home, while also paying for the construction of those in larger public buildings. In Canada, no formal plan was instituted.

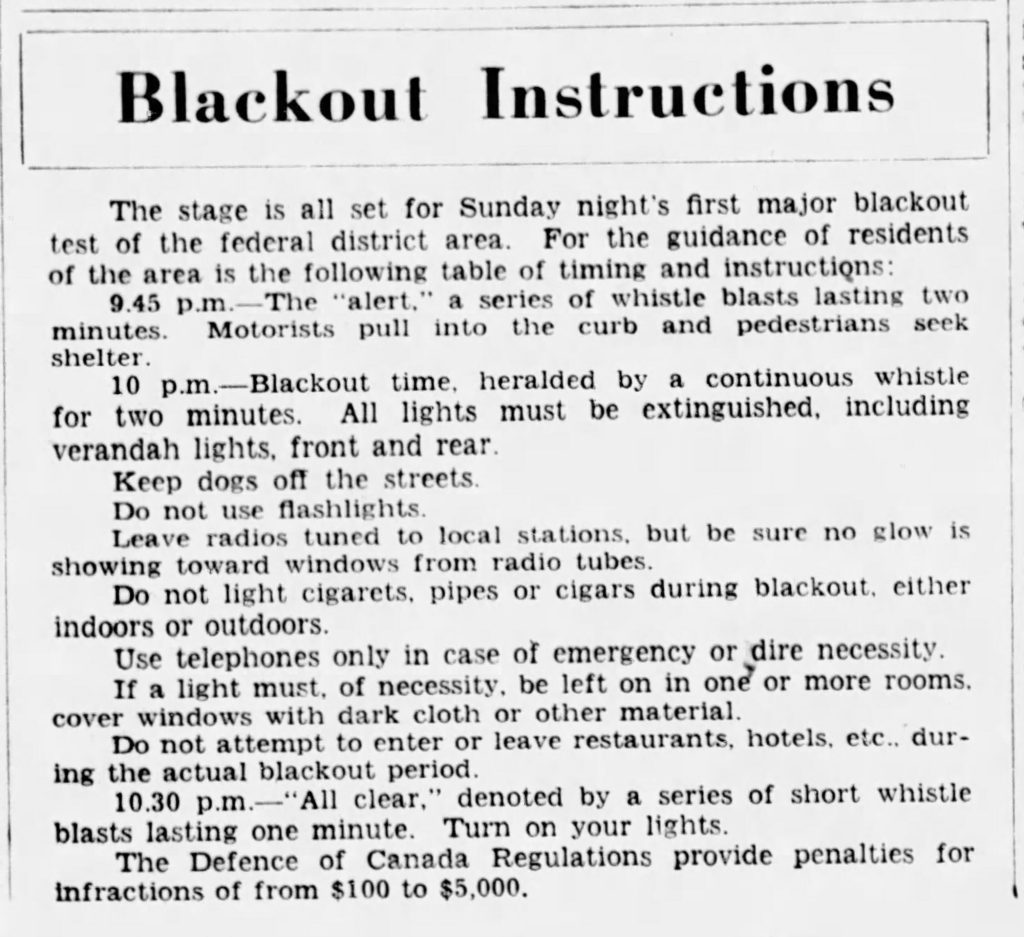

Ottawa held its first blackout test on Oct. 26, 1941. The federal government had installed air raid sirens in just seven locations in Canada — including one in Ottawa — which was installed on the roof of No. 2 Hydro Sub-station at the corner of Carling and Bronson.

At 9:45 p.m. on that date, the air raid warning was sounded from 47 points in Ottawa-Hull, using the siren, railroad engine whistles, factory whistles, radio broadcast of recorded siren sounds, and other methods. Then the official “action warning” siren droned at exactly 10:00.

“The wave of screaming screeching sirens blew like a gale over the city,” reported the Citizen as the blackout began. Homes and any open restaurants or businesses were required to turn off their lights and lock their doors; automobiles and street cars were halted and lights turned off; and everyone was to remain inside until the “all clear” was sounded.

Misunderstandings a benefit to the enemy

The test seemed to go well, except for an error made by the Ottawa Light Heat and Power Co. They failed to turn off the “whiteway lights” on Wellington from Elgin to Bank, “illuminating the buildings for the benefit of the theoretical enemy,” noted the Journal. These strong lights remained on for half the blackout, as an employee had misunderstood and turned off only a bank of lights in Westboro.

By 1942, the threat of an attack was heightened. The city was concerned about aircraft flyovers dropping incendiary bombs on houses and businesses. Ottawa put extra emphasis on first ensuring that water services and fire protection were maintained in a constant state of readiness.

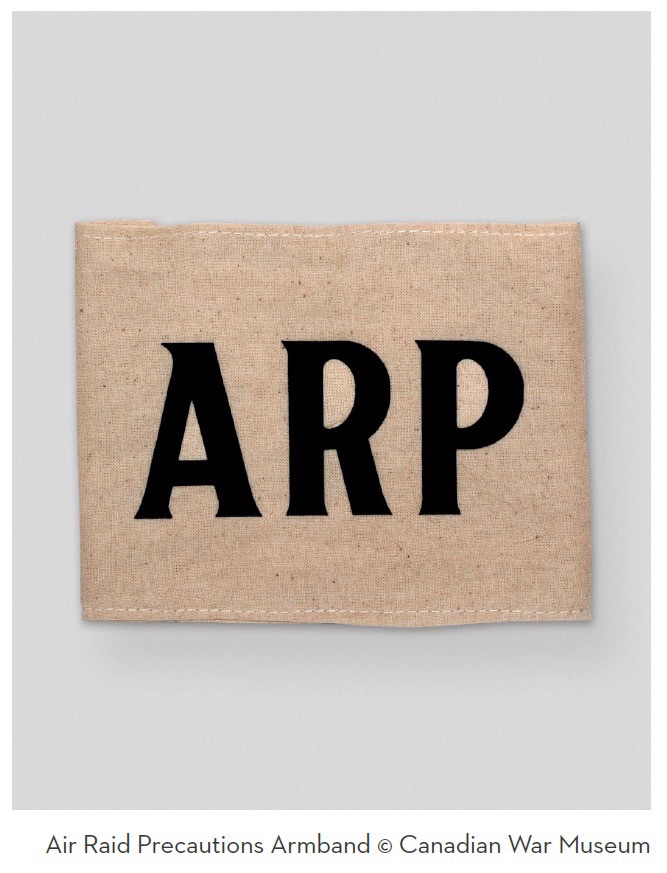

Ottawa Fire Chief J.J. O’Kelly launched a major campaign to educate citizens on how to fight incendiary bombs and the resulting fires. A system was put in place of having two to four “wardens” on each city block — plus larger teams representing commercial businesses — to work with the fire department. Wardens were trained on providing lectures in the methods of dealing with bombs and fires, and travelled to every home in their designated area to provide these instructions. These volunteers wore A.R.P. armbands as identification and many also wore a combat (Mark II) helmet.

The instructions stated that in the case of a bomb raid, “each householder must be his own fire fighter. The fire department will be too busy on large fires to fight one in your house, and your insurance will not protect you in case of loss.” It also noted that bombs “will likely penetrate the roof and lodge in the attic”, and thus this was where it was most likely they would have to be dealt with.

Attics were to be cleared of all inflammable material, and two or three 10-pound paper bags of sand were requested to be kept in the space along with a shovel and a hoe. Citizens were told not to use fire extinguishers or a jet of water to extinguish the bomb, as it could cause greater damage.

“If you can reach the burning incendiary bomb within a minute or so, you can easily extinguish it,” stated the fire department. “If you take five minutes you will be too late… Act very quickly and do not be afraid. Plenty of women in Britain have successfully fought incendiaries.”

Sand was seen as the best solution to fight these potential bombs and fires. The City acquired huge amounts of sand and distributed it throughout the city to various hubs, mostly schoolyards, for pickup in April 1942. The main distribution point for Kitchissippi was on what is now Harmer, near Byron Avenue.

City council was discouraged when very few citizens took the warnings seriously, and the sand remained largely unclaimed. An editorial in the Citizen surmised that Ottawans suffered from apathy and laziness, with residents used to having services delivered direct to their doorstep. ”A good number of us think it is a great imposition to fetch a few pails of sand a few blocks,” it wrote, though it also added that likely many Ottawans simply felt that if the city were ever bombed, a few little pails of sand wouldn’t make much of a difference.

To solve the issue, the Junior Board of Trade oversaw the distribution of buckets of sand to every individual house in Ottawa and Westboro, courtesy of local high school boys who were paid in soft drinks for their hard work.

Deputy Chief Engineer of the British Ministry of Home Security, Professor Frederick Webster, visited Ottawa in February of 1942 to advise on how Canada could implement air raid shelters and camouflage for industrial buildings.

The first air raid shelter built in Ottawa was actually constructed in Kitchissippi. It was privately built as part of a new house on Parkdale Avenue near Ruskin in the late summer of 1942. The shelter consisted of a large room 12 feet by 20 feet, built underneath the garage, and connected to the house by a nine-foot long tunnel, which was 5’ high and 5’ wide. The tunnel and the floor of the garage acted as the roof of the shelter, which was built of concrete.

By 1943, the threat of air attacks had all but disappeared, and the Air Raid Precautions groups were disbanded.