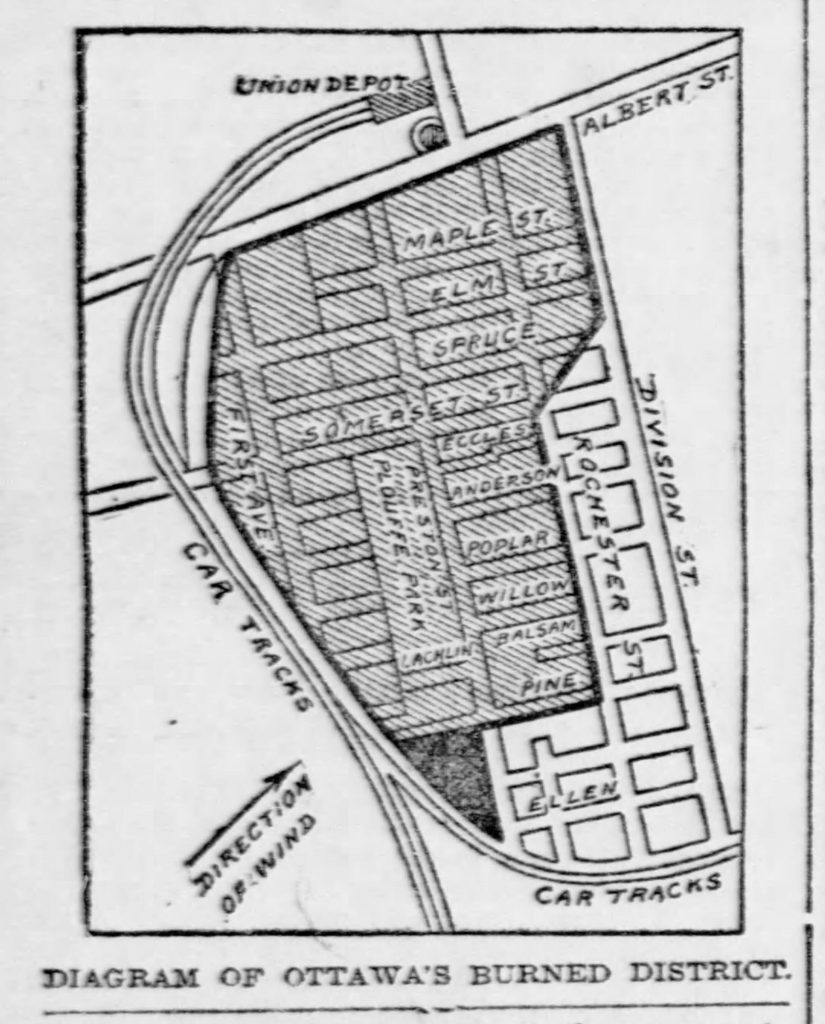

You likely have heard about the Great Fire of 1900, which decimated the City of Hull and caused $6.2M in property loss in Ottawa. The blaze left 14 per cent of the city homeless and leveled the area between Booth and Preston all the way to Carling.

However, what is remembered far less today is that this area of west end Ottawa suffered an almost identical fire just three years later in 1903. It forced Ottawa politicians to make some tough decisions by standing up to lumber companies who had yielded control over the city since the days of Bytown.

It was May 10, 1903, a Sunday afternoon when the sun shone down on the paved streets of west Centretown, fringed with fresh green lawns, stretching out in front of rows of impressive new houses constructed following the catastrophic three years prior.

Along the Canadian Atlantic Railway line (now the Trillium O-Train Line), J.R. Booth piled massive quantities of lumber. He had done so prior to the 1900 fire, and re-piled it afterwards. By 1903, the stacks were high once again, posing a major fire risk.

Tempting fate, it was here within the lumber piles, just west of Preston at the end of what is now Louisa Street West, where the first smoke was seen at 3:30 p.m.

Minutes later, entire blocks of houses were up in flames. Carried by a wind gusting to the northeast, the flames moved quickly. Local residents who were at home had only minutes of warning.

A mad dash for safety

Many frantically loaded up rigs, wagons or sleds — whatever they could find — with their belongings and furniture. Pianos were dropped from second storey windows. Sick and invalid family members were carried out into the street. Those who lived through the 1900 fire recalled how futile it was to move possessions. Many just grabbed what they could easily carry and ran.

Bottlenecks occurred on many streets and most exit points in the panic. In many cases, the fire simply was moving too quickly, and all had to be abandoned. One family used an excavated hole in the roadway at the corner of Eccles and Rochester in an attempt to save their household items.

As the massive Booth lumber piles burned, the wind carried the embers throughout the neighbourhood. People took shelter in Plouffe Park, where they piled their possessions. But the Park offered no protection. The grass carried the fire, and the entire park became an inferno.

Compounding the troubles, just as the fire brigade arrived, the city’s waterworks system failed. A known leak in one of the mains had been under repair, and just a few minutes after the water was turned on to fight the fire, the pipe burst, flooding the pumping station. For half an hour, when the water was most needed, it was unavailable. Eventually, the valves to the broken main were shut off to allow for the other pipes to work. However, frustrated firemen hooking into the 80 hydrants in the area found weak pressure, if any at all.

Local militia, a fire brigade from Montreal, and dedicated community members helped in the battle. “Alderman Moise Plouffe in whose ward the fire played its wildest pranks,” reported the Ottawa Citizen, “was one of the coolest cucumbers on the vine. He was here, there and the other place all the time.”

Equal complement was paid to Hintonburg Alderman Sam Rosenthal: “The popular civic commoner from Victoria Ward worked like a bunch of beavers. He put to shame many muscular men who preferred to recite chapters on How to Fight Fires, rather than to lend a hand to save some humble home or its contents.”

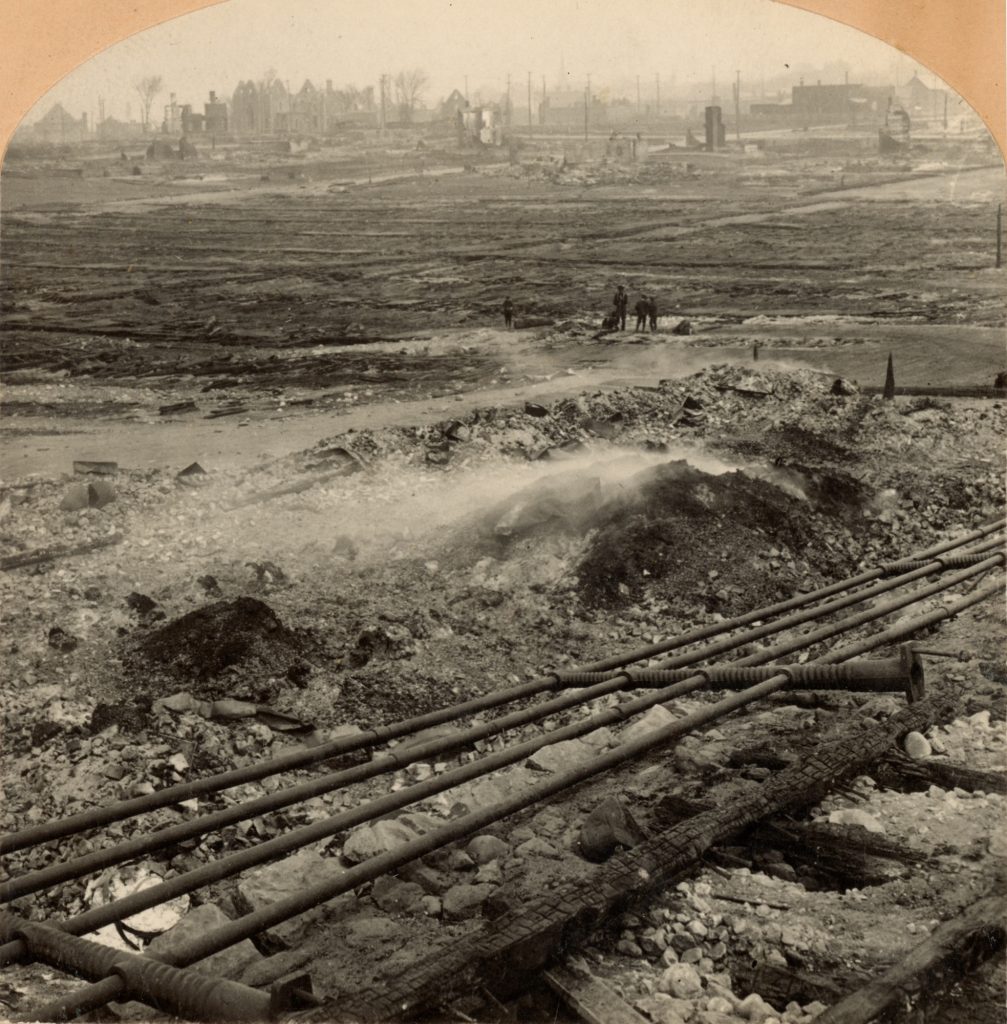

The fire took six hours to get under control and burned until after midnight. The area between Preston Street and Booth Street from Albert Street to south of Gladstone Avenue was wiped out, just as it had been in 1900. In the end, over 240 homes were destroyed, and between 800 and 1,000 residents were left homeless. Ten million feet of lumber burned. The total loss was $750,000 — about one-fifth of the loss Ottawa suffered in 1900.

Hintonburg once again was luckily preserved, saved only by the wind that blew east. The community fire brigade worked hard to protect the village, particularly watching Oliver’s Mill on Gladstone Avenue and Mason’s mill at the end of Bayswater Street. Hintonburg’s pumping system proved superior to that of Ottawa’s, providing sustained strong water pressure whenever it was needed.

Hintonburg also provided great relief to fire victims, with many temporarily opening their homes to those who had lost everything. Some who had nowhere to go simply camped in the area until they had other options.

Fire could have been much worse

The fire brigade focused on the former site of J.R. Booth’s mansion at the corner of Albert and Preston Streets, where its ruins still stood from the 1900 fire.

Large wood piles were now on this spot, and began to burn fiercely. Across the street on the north side of Albert,were more lumber piles, as well as the CPR depot and yards, and the working class homes of LeBreton Flats. As embers and sparks blew over to this area, firefighters and homeowners worked tirelessly.

If it wasn’t for their quick action, the fire easily could have eaten through these areas and moved onto Hull — the reverse of how the 1900 fire had spread.

The Somerset Street Bridge was badly burnt, causing streetcar service to Hintonburg and Britannia to be severed. Miraculously, the bridge was repaired and new tracks laid, and service was restored just three days later.

“As night fell and the red moon rose full over the city the scene witnessed by the crowds gathered on Primrose hill was one of weird splendor”, reported the Citizen, “To the east the city looked peaceful, and almost serene in its security. All to the south was a glowing furnace now dying down into crimson heaps, with here and there spirits of flame from thick lumber piles.”

Though officially the death count was zero, the Ottawa Journal reported that a small Italian child had to be moved from his sick bed with rheumatism to the shed of a neighbour’s residence. He passed away just half an hour after being moved, the shock of the situation overcoming him.

Attention soon focused on the cause of the blaze, and immediately the police charged John White with arson. He was out on parole after having been jailed in 1895 for setting fire to J.R. Booth’s lumber piles.

White went through the court process over the next few weeks, but ultimately the Judge ruled he could not be found guilty due to lack of evidence. The Crown attempted to argue that the circumstances were so extraordinary and so suspicious that White had to be connected.

Ignoring his prior history, the fact that he was seen — and admitted to — decoupling one of the hoses from a hydrant, moved a line of hose 30 feet away from the fire, and all his statements were contradicted by other witnesses, did not matter. He was also the first to discover the fire and pulled the alarm on the fire box, which was “the outcome of drunken imbecility,” said the Judge.

White never took the stand himself, and the defense did not call any witnesses. White in the end pleaded guilty of impeding the firemen, using his drunken condition as his excuse, and owed just a $52 fine.

Rebuilding again

Reconstructing the west end for a third time was not going to be easy. Most residents were “double victims” of both fires, and were reluctant to do it again.

“I’ll never live in the west end again!” cried one woman to the Citizen reporter as she walked around town carrying all her remaining worldly possessions under her arm.

One thing was for sure. The massive lumber piles within the city limits had to go. This was obvious to the citizens of Ottawa, to local politicians, to the insurance companies, and to the world media, who were unanimous in their scathing reports of the irresponsibility of Ottawa to continue to allow them.

An Ottawa Citizen editorial called the piling of lumber within city limits “suicidally dangerous in a municipal sense”. The insurance underwriters immediately applied a hefty surcharge to all homeowners in Ottawa, applicable for as long as the wood piles remained. This caused much consternation to residents, many of whom suddenly could no longer afford critical insurance.

Council immediately passed a by-law requiring all piling to cease, and for all lumber firms to remove their holdings to locations outside the city within six months.

Yet, as time ticked on, the lumber companies did not only move their piles, they began to re-pile the old ones. Unbelievably, the firms began to exert influence over council members, perhaps even buying them off. Mayor Fred Cook suspended any efforts at enforcement of the by-law, and within a few months, Council rescinded the by-law.

The public was in a furor. A new by-law basically gave the lumber interests everything they wanted. Lumber firms complaints that the land outside city limits was hard to prepare, no rails were available to build lines, nor was labor available to do it, fell on deaf ears. The issue became a key election issues that winter, costing several council members their jobs.

In 1904, a compromise was made, placing restrictions on the sizes and locations of piling areas in the city, a requirement for the fencing in of yards, and for a watchman.

The piling of wood remained an issue for decades. In 1909, the Board of Control passed a by-law ordering removal of lumber piles south of the Somerset Street Bridge, and other areas of Ottawa, but the issue remained as lumber firms remained in business within the city, albeit with some restrictions.