by Dave Allston

As shared in part one, by 1909, the future Hampton-Iona neighbourhood had a new name: “Laurentian View”—its first commercial shops, landscaped recreation grounds, and new houses were going up as fast as wood and nails could be procured.

The end of 1909 also saw the arrival of the neighbourhood’s first key figure, John Y. Morrison. Morrison was 52 years old and was a farmer in Bristol, Quebec for most of his life. He sold his farm, purchased the lot at the northwest corner of Hilson and Iona and constructed a small, mixed commercial-residential building at 504 Hilson, which still stands today. The upstairs had two apartments, while the downstairs became a grocery store operated by Morrison.

Later described as a “man who had always been the same in boyhood, as a man in the country, and as a man in the city; a man worth knowing, of sterling character and a faithful worker in whatever he took up,” Morrison helped pursue advancements for the growing little community.

One of the first steps to put Laurentian View on the map (literally) was to obtain its own post office. Morrison was selected to be the first postmaster, with the post office located in his grocery store. The post office opened on Aug. 1, 1911 and served the neighbourhood until 1942.

A tragic event occurred nearby a few years later when Morrison’s wife Lydia was struck and killed by a streetcar at the corner of Hilson in December 1917.

The beauty of the neighbourhood convinced his young son G. Cecil Morrison and his son’s friend Richard Lamothe in 1914 to acquire the neighbouring lot and open a small bakery, which they called “Standard Bread.” They acquired two secondhand bread wagons, brought two horses from Lamothe’s farm on Calumet Island, and opened two bread-delivery routes in the west end. Lamothe did the baking and they hired two delivery drivers. They ran it as a part-time operation for a year, before deciding in 1915 to make it a much larger operation.

However, WWI was underway and there were shortages of food and manpower. As well, enlistment was a big deal at the time. Well-known area resident Fred Heney was the local enlistment supervisor. He cut a deal with Lamothe and Morrison, who worried about having to close the bakery if they both got called to enlist. Heney agreed it wasn’t right to shut it down.

“I’ll tell you what I’ll do,” said Heney. “If one of you fellows enlists, I’ll exempt the other.”

Cecil was engaged to be married and had parents to help support, while Lamothe was single, so Lamothe enlisted with the Royal Canadian Engineers and went overseas until 1919. Cecil agreed to pay himself only the same salary as Lamothe was getting army pay, and then any profit above that would be split 50-50 when he returned.

Following WWI, Standard Bread grew in a big way. In 1919, the business expanded to 19 bread routes. The company, which had started out on $25 capital, was valued at $700,000 in 1926. It was then that Morrison and Lamothe needed bigger quarters, so they built the Standard Bread building on Gladstone Avenue in 1924 and moved. The original factory on Hilson was sold and soon after demolished. But the Hilson Avenue legacy of the Standard Bread Company is an important one.

Meanwhile, the neighbourhood continued to grow quickly. The Laurentian View Boy Scout troop was established in 1911. Hilson School was completed in the fall of 1914. A community association was formed (then called a ratepayer’s association). The Laurentian View team had a strong entry in the annual Britannia Streetcar Line baseball league, and their ball diamond was a top spot to hold games. More and more lots were being purchased, and the sounds of construction filled the air all year long in Laurentian View in the 1920s.

In November 1915, a new enterprise arrived when I.A. Scott began a business offering Laurentian View Spring Water, “Direct from the Spring,” a five-gallon bottle for 25 cents. The location of this spring has been lost to time unfortunately!

WWI saw many of the young men of Laurentian View go off to fight in the war, but luck was on the side of most of these men, as a surprising majority were reported to have returned home. Sadly, Pte. Alfred Evans was killed in action in May 1918. Just prior to the war, Evans had purchased a lot and constructed a home at 189 Devonshire Place on payments from prominent Westboro citizen William A. Cole. When Cole heard of Evans’ passing, he notified his widow—who was now alone with three young children—that all interest due or to come due was cancelled, a loss to Cole of some $300. Thus the family was able to stay in the home, and it remained in the family until 1987.

Mail delivery arrived in 1942 after years of anticipation, and with it, came improved civic addressing. Many streets were renamed due to duplication (Kirkwood Avenue, for instance, was originally two streets: Heney at the north end and Holland at the south end), leading up to Laurentian View becoming part of the City of Ottawa in 1950.

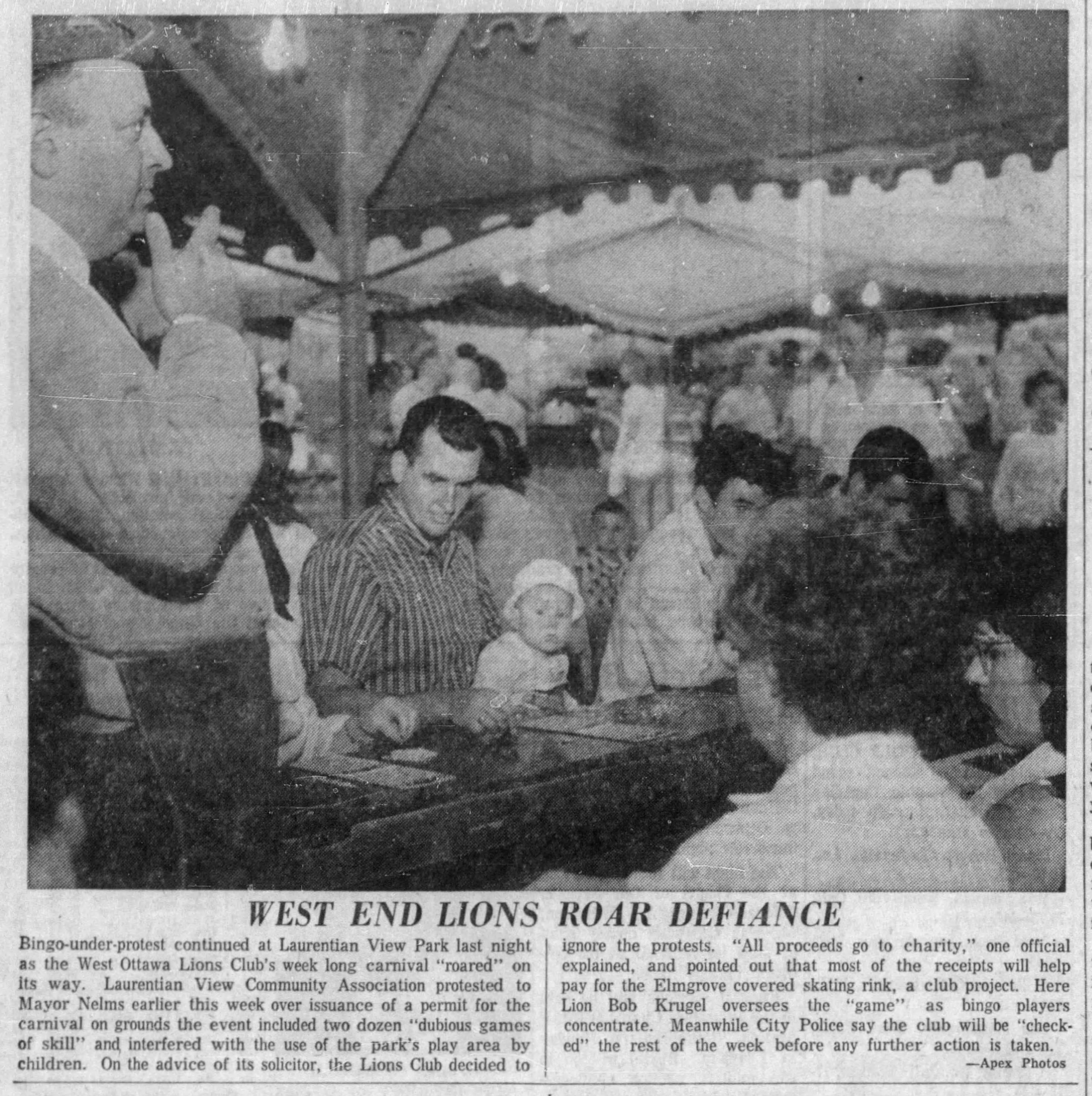

The area would continue to grow, particularly after the conclusion of WWII and the major housing boom saw most of the last undeveloped pockets of land fill up with small subdivisions. The ball diamonds, rink and park at Hampton Park continued to be known as “Laurentian View Park” all through this period.

Hampton Park Plaza arrived off the success of Westgate and Carlingwood malls, which opened in 1954 and 1955, respectively. The Dominion grocery store had opened in 1954 to much fanfare, revolutionizing how local residents bought their groceries locally (overnight putting out most of the small mom and pop shops that had been sprinkled throughout the neighbourhood the last 40+ years). The long-awaited mall came later, opening in October of 1961 as “Ottawa’s first 2-Storey shopping centre”, and included a 24-lane bowling alley, the Queensway Lanes.

The mall clearly led to a shift in neighbourhood identity, including a near-total removal of the 50-year old name “Laurentian View.” Between 1961-1962, all references to the name (in the community association, the recreation association, the rink, the ball diamond, etc.) all changed over as the neighbourhood adopted the name “Hampton Park” instead.

The name Hampton Park originated in 1909, chosen by real estate investors John C. and Herbert Brennan as the name of their incorporated company, who laid out the adjoining neighbourhood and wanted to create a sense of prestige and stature, choosing the name after an affluent district of London, England, as they did with many of the streets.

In June 1969, the city recreation budget was cut for a second year in a row. The Hampton Park rink was one of five city run rinks (all west of Bronson) to be shut down due to low attendance. At the same time, it was announced that for all city run rinks, the recreation and parks department would continue to provide materials, but all maintenance would be the responsibility of community groups—a big change, which the local association took up at that time.

The Hampton-Iona Community Group name dates back to about 1982, when the old community association had slowed in activity over several years, and Iona Park had become neglected and overgrown. The group soon succeeded in campaigning for a skating rink, new playground equipment, trees, benches and a change trailer.

The group raised $3,500 through bake sales and garage sales, and the City paid the rest of the $16,000 price tag for landscaping, a drainage system, a playground and an outdoor rink. The winter carnival in February 1986 celebrated the “rebirth” of the park, which, just four years earlier, was a “swampy, neglected piece of land with a couple of rusty swings and a vandalized shack.”

The management of the park and rink remain one of its key roles in the community today.

The name Laurentian View has all but disappeared except for an occasional reference. The smells of Standard Bread are long gone, and, sadly, the old convent home has a precarious future. But, there is still so much history in this community, that this article only scratches the surface of the whole history of this historic, vibrant neighbourhood.