By Dave Allston

For a brief period a century ago, excitement—and probably a little bit of fear—gripped Westboro on the discovery of a wild animal that had strayed from its usual habitat.

Who can forget the moose that wandered onto the 417 eastbound by Pinecrest in 2018 or the “sleepy” 150-pound black bear cub that was found on Denbury Avenue in 2006?

A similar story from the early days of Westboro tells of the almost unbelievable arrival of a surprise visitor to the neighbourhood.

On an early Sunday morning in May 1919, three local teenage boys “out for a morning ramble in the bush” came across a large lynx perched in a tall tree in Hampton Park.

Of course, lynx cats have never been prevalent in the Ottawa Valley, and any sightings over time have been extremely rare. The lynx is a solitary cat that typically sticks to the remote northern boreal forest within Canada.

The two youngest boys, Billy Deans and Eugene Barry, were residents of Hilson Avenue, and were surely very familiar with the Hampton Park woods behind their houses. In 1919, the west end was still in transition from farmland and woodland to residential, and so vast swaths of the neighbourhood still featured thickly wooded areas. Early Hampton Park would have been one such area, its area nearly double its present-day size as it extended towards Fisher Park.

The pair were out for a walk with a friend (noted only in one article with the name ‘Stewart’) and were accompanied by a dog, who suddenly darted over to a tree and began barking excitedly. Billy and Eugene took a look up into the branches and were shocked to see a large lynx suspended on a bough.

Amazingly, their first instinct wasn’t to run, nor was it to even leave it alone (as most people in their shoes would have done). No, their plan was to get the lynx out of the tree and capture it.

They first attempted to throw stones at the cat to get him down, but it would not budge. So Billy Deans somehow located a rope, made a lasso with it, and successfully threw a slip noose over the lynx’s head.

It was then that “the fun commenced,” wrote the Ottawa Journal. “The hunted animal endeavoured to make the best use of its agile legs, with the result that Deans was given a merry chase to hold it in.”

The lynx was then pulled to the ground, but it landed right on top of Eugene, breaking his arm and badly injuring his shoulder.

The frightened cat made valiant attempts to fight back and escape, but the two brave (or foolish?) boys persisted and managed to tie it up, and loaded it onto a wheelbarrow, which they wheeled down Hilson Avenue in triumph. The lynx was then held captive in the Barry family garden, while the boys went to the hospital to have Eugene’s broken arm looked at.

Cecil Morrison, proprietor of the popular Standard Bakery (which had its factory on Hilson at the time), dropped by and viewed the lynx (as likely the entire neighbourhood did that day as word of the lynx capture spread), and noted to the Ottawa Citizen that It was a “remarkably fine specimen.”

The lynx was described as definitely being of the North American and Canadian type (the largest and most ferocious of its species) and “apparently well-nourished, brown in color with black stripes, and tufted ears” and “between three and four feet long, as big as a good sized collie dog and must weigh about 60 pounds.”

Where it came from is difficult to guess, but it surely travelled far and through unfamiliar territory to arrive in Hampton Park. Typically, a lynx will not come near civilization except when food supply gets low. In hunting through vintage newspapers, 1907 was a year where three lynx were captured and killed in the Ottawa area, including one on a farm south of Britannia at Greenbank and Baseline. The sudden appearance of three lynx within a one-month period during the summer, when food would not have been scarce, confounded local animal experts.

However, the 1919 sighting was thought to be the first time in years that a wildcat had been seen so near to the city, and finding recordings of other sightings over Ottawa’s history (aside from 1907) was nearly impossible.

The news of Billy Deans and Eugene Barry’s big capture spread to the city and was of particular interest to the R. J. Devlin Fur Company, at 76 Sparks St. (between Metcalfe and Elgin). Devlin paid the boys to display the lynx in his renowned front window display. For a day or two, Sparks Street pedestrians would have been able to come face to face with a live lynx, with just a pane of glass in between. Ironically, A.J. Alexander Furs—Devlin’s competition across the street—was advertising lynx furs for sale that same day!

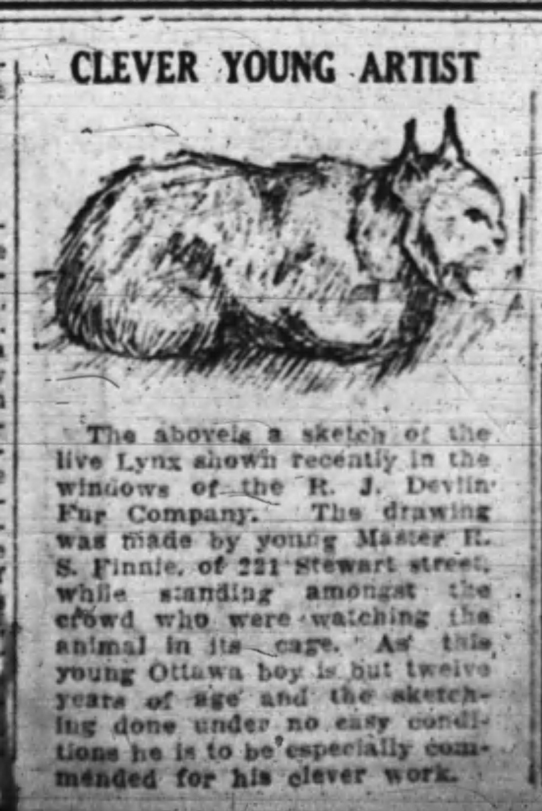

The appearance of the lynx in the window created excitement in the city, and both the Ottawa Citizen and Ottawa Journal newspapers published drawings made by 12-year-old R.S. Finnie of Stewart Street of the lynx (publishing photographs in newspapers in that era was still rare and costly, but an illustration could be run much easier).

There was no record of what happened to the lynx or where it ended up (though one can assume, what with his last public appearance being in the window of a fur shop).

Fast forward 73 years, when Ottawa received a Triple-A baseball franchise, the name Lynx was the surprise selection from a name-the-team contest that saw 35,000 entries submitted. Owner Howard Darwin favoured the name because it was short and could be translated the same in both French and English. Though the name eventually grew on local ball fans, it was always an odd fit.

Now we know, it was indirectly an obscure homage to the handful of lynx that have popped up within the city like a lost tourist, as one unlucky lynx did 103 years ago in Hampton Park.