By Dave Allston

Holland Avenue is one of Kitchissippi’s most significant streets, one which has seen constant development and change over the years. Urban intensification, most notably related to the future of Tunney’s Pasture, will soon see Holland change even more.

Did you know that Holland Avenue first existed as a vista for the first streetcars into the west end? Did you know that its namesake is actually for two men, brothers who were two of the most visionary, entrepreneurial citizens in Ottawa’s history, who not only made their home in Kitchissippi in the 19th century, but who directly significantly impacted the design and development of much of the neighbourhood? It’s true!

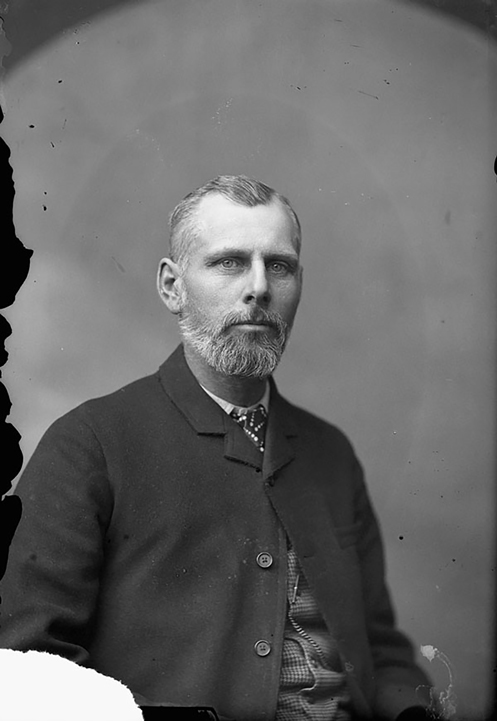

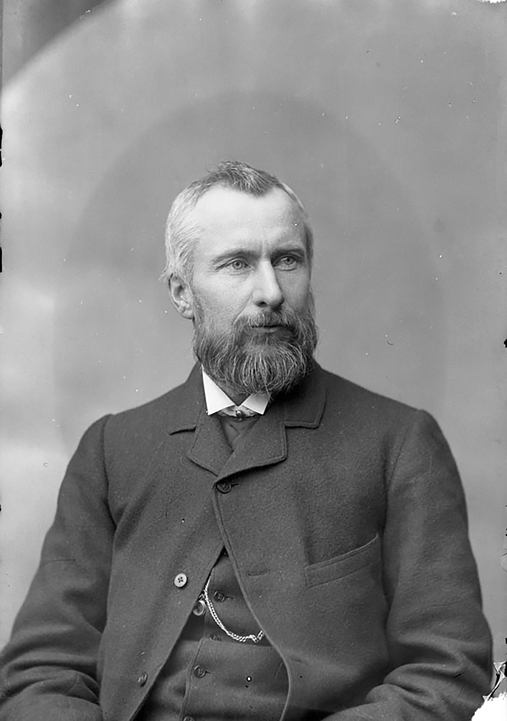

Andrew Holland (b. 1844) and his brother George Holland (b. 1846) were the two sons of William Lewis Holland and his wife Charlotte Clarke. William had immigrated from Ireland, met and married Charlotte, and the couple settled in Bytown as two of its earliest settlers, establishing a business on Sparks Street.

Andrew and George had similar paths, both receiving postsecondary education, before entering the world of journalism. Andrew wrote for newspapers in Ottawa, while George contributed to papers such as the Toronto Telegraph, Chicago Times, Washington Post and New York Herald. George also served in the volunteer militia during the Fenian Raids of 1866, receiving a medal.

In January 1873, the brothers became owners and editors of the Ottawa Citizen, then later joined the reporting staff of the House of Commons in 1875. Two years later, in 1877, they would become the official reporters of the Senate of Canada, where George would begin the Hansard system of debate reporting. He was a Senate reporter for 40 years.

The pair were enthusiastic promoters of new inventions (such as Thomas Edison’s phonograph) and were pioneers of the typewriter business in Ottawa, acclaimed for their ability to take and transcribe shorthand notes.

Later, Andrew took on new interests, travelling to Australia in 1892 and establishing the Canadian Australian Royal Mail steamship line, which provided monthly service and established early trade between the two countries.

Andrew was also a charter member of the local Canadian Club and member of the Board of Trade from its inception. He was known as the father of the Federal District scheme, which was the predecessor to the National Capital Commission (NCC). He also was engaged in the lumber business for 35 years, owning extensive timber limits.

George became known for penning an English version of Calixa Lavallée’s “O Canada” anthem in 1910.

The brother’s local ties were also significant. In 1887, both brothers moved to Kitchissippi. George and his wife Allison Hilson Holland acquired 12 acres of Hon. James Skead’s property, including the impressive villa house then known as “The Elms,” a property located on the south side of Richmond Road—which still stands today. Meanwhile, after the passing of Joseph and Robert Hinton, Andrew acquired the Hinton family farm, moving into the beautiful brick home known as “Richmond Cottage” on Wellington Street, which stood about where Morris Home Hardware stands today.

There was a strategy to their relocation from central Ottawa. Andrew was working with Thomas Ahearn and Warren Soper of the Ottawa Electric Company (OER), who were long-range planning for the establishment of streetcars for Ottawa. By acquiring farmland in the west end, where the city was projected to grow, the Hollands were investing in the future—a future that would see streetcar lines run directly through their soon-to-be-prime real estate holdings.

The group formed the Ottawa Land Association (OLA) syndicate, buying up additional farms and failed subdivisions in the area in preparation for the streetcars to come. Andrew contributed his lands to the syndicate.

In 1895, the OLA laid out a plan for the area from Carling to Scott, and Harmer to Parkdale. Within the heart of the plan was the establishment of a large boulevard, 80 ft. wide, aptly named Holland Avenue. Tracks would run down the centre of the roadway, taking streetcars from Wellington Street South to the Experimental Farm.

Holland Avenue was still just farmer fields when the OER ran their double track overtop in 1895, with a line of trolley posts between them, with arms branching out over both tracks for the trolley wires, but also to eventually hold electric street lights, telephone, telegraph and other wires. A tunnel was also built underneath the crossing tracks of the old Ottawa, Arnprior and Parry Sound Railway (now the Queensway). The line officially opened in April of 1896, advertising a 15-minute run to Elgin Street, and in 1900, a new connection was added at the future Byron Avenue, taking residents out to Britannia Beach.

The OLA also set aside a huge chunk of land just south of where the Queensway runs today, and created the West End Park, an enormous amusement park and entertainment hub, with large touring shows featuring performers and circus acts.

The Holland brothers continued their friendship with Thomas Edison, and in 1896, a significant moment in our local history occurred when the brothers brought Edison’s latest invention—the vitascope—to Ottawa. Two years prior, the Hollands had acquired the Canadian and Eastern U.S. distribution rights for a popular previous invention, the kinetoscope, which was, essentially, the first moving picture device. Andrew opened the world’s first moving picture parlour in New York City in April 1894. Seven months later, he brought a kinetoscope to Ottawa for a demonstration. But the vitascope was more advanced: it could project moving pictures to allow for a large audience to watch. Thus, it was at the West End Park on Holland Avenue in July 1896 where the vitascope received its first Canadian demonstration to awestruck audiences.

Infrastructure construction on Holland Avenue itself was slow, as projects like having a water and sewer system were still a few years away. Even building a drain to prevent flooding, particularly in the spring, was a multi-year ordeal. The first structures on Holland were a small OLA advertising office and a streetcar “waiting room” shelter at the corner of Wellington.

The first building on Holland appeared at the northwest intersection along Wellington (the site of Second Cup today), constructed in early 1898 by Hintonburg merchant Thomas A. Stott. It contained a grocery store and a double dwelling, first occupied by carpenter Archibald Campbell, and featured the first Holland Avenue civic address: 107 Holland—when odd numbers were still used on the west side of the street!).

The street gradually filled up, though certain parts were slower to be developed than others (Holland Avenue was not even paved north of Spencer Street until the late 1940s!). The Ottawa Electric Railway owned the stretch of land from Byron halfway to Wellington and kept it as yard space for materials and old streetcars, finally selling it for development in 1947, when a series of similar duplexes were built on this stretch.

Big industry arrived in 1920 with the arrival of Beach Foundry at the north end (which became Holland Cross in 1986). Fisher Park was also established in 1920, with the high school opening in 1949. The Elmdale Tennis Club initially was located on Fisher Park grounds, but moved to its current location in 1948.

The Electric Railway substation at 340 Holland, just past the Queensway, opened in 1924 to feed power to the line—now, the station building is a heritage site.

The street had its first high-rise apartment when the Holland Court opened at 199 Holland in November 1963. Of course, Holland featured a vintage three-storey apartment house at the corner of Wellington, known as the Goldwyn Apartments, from 1924 until it was destroyed by fire in 1996.

Meanwhile, at the south end of Holland, the Civic Pharmacy building opened in September 1960 to serve patients of the Civic Hospital and other new medical buildings.

Over 120 years later, the contributions of Andrew and George Holland cannot be understated and we have Holland Avenue to remember them by.

The Passing of Andy Billingsley

On July 25, Kitchissippi lost one of its most dedicated historians, Andy Billingsley. Andy was one of the proudest residents of the Civic Hospital neighbourhood and worked tirelessly to chronicle its history. He helped start up the CHNA History and Heritage Committee, and he delivered detailed presentations and walking tours from the heart, making local history come alive. He was passionate about the streets, the homes, and, especially, the people who helped make the Civic neighbourhood the great place it is. I’ll miss the glint in his eye as he shared a new finding about a local history topic or helped me with a question I had. Condolences to his family and to all who, like me, will miss him greatly. Please take some time to visit the History and Heritage section at chnaottawa.ca to view some of his hard work—a great legacy to his community.