By Dave Allston

Though Kitchissippi’s first Jewish residents had arrived in 1903, by the onset of the First World War in 1914, there were still just two resident families. That would change quickly.

The first Jewish families west of Hintonburg began to settle in 1914. Isaac Zidoff and Nathan Wolfe were relatively new immigrants to Canada when they purchased the small house at 539 Hilson Ave., and rented it to a series of Jewish peddlers over the next four years (the first being Samuel Shefenberg). In 1918, Zidoff himself moved in, constructed a small one-storey addition at the front and opened a fruit and grocery store (Zidoff, his wife Hannah, and three school-aged children later moved to Chicago in 1923). Wolfe, meanwhile, would remain in Ottawa for the remainder of his life — though he was a tiler by trade, he would become a prominent real-estate investor.

A block over to the west on Kirkwood Avenue arrived brothers Samuel and Jacob Ages in 1916. The pair were only 26 and 22 years old, respectively. They purchased a house at 544 Kirkwood Ave. (then known as “Heney Avenue”), constructed a large ice house in the backyard and became ice dealers. Though Jacob remained involved in the ice business in the west end until refrigerators ran ice dealers out of business in the 1940s, Samuel’s story was a sad one. His wife died of Spanish influenza in 1918, leaving him a widower with five young children. Sadly, Samuel died in a tragic sleigh accident a little over a year later when his horse darted suddenly across the CPR tracks at Churchill Avenue.

As far as Westboro goes, Benjamin Bodnoff arrived in mid-1919 and opened a dry-goods and clothing shop in part of what is now the Lululemon building at Richmond Road and Churchill Avenue. Though Bodnoff was long-considered the first Jewish resident of Westboro (even noted in the newspaper coverage of his death in 1960), research shows the first Jewish family was actually that of Samuel and Mary Sommers. In 1916, the Sommerses moved on to Churchill Avenue into what is now 342 Kenwood Ave., which for many years had an extra addition fronting Churchill Avenue that served as a grocery store for Highland Park. Sommers and his family ran it from 1916 until 1923, when they moved to Los Angeles.

Bodnoff’s contributions were exceptional, and even if he was the second arrival, his years of leadership in the board of trade — and in the development of Westboro Village in general — certainly established him as one of the most influential figures in early Westboro history. His pride in Westboro and close association to the Jewish community in all certainty meant that Bodnoff was likely largely responsible for the quick growth of the Jewish population in that part of Kitchissippi, perhaps even helping mitigate discrimination experienced elsewhere.

The years following the First World War became a difficult time for Jewish people worldwide. For reasons simply unconscionable a century later, Jews faced anti-Semitism throughout the world. Sadly, Canada was no different. Though at the time Canada was still accepting significant numbers of Jewish refugees escaping famine, poverty and increasing persecution, Jews still faced growing inequity and restrictions here. But, in what should be considered a proud piece of our local heritage, our neighbourhood appears to have been a hospitable destination for Jewish residents.

As more Jews were escaping the growing, serious unrest in Europe, Hintonburg in particular became home to an incredible arrival of Jewish families. In the space of less than two years between 1919 and 1921, no less than 14 Jewish families moved into Hintonburg. Wellington Street West virtually became a mini Jewish district, with 11 families residing directly on Wellington (all except one between Merton and Carruthers), and all but one of which opened a commercial business!

Though some would remain only a short time, most of these residents would stay for the long term, many permanently.

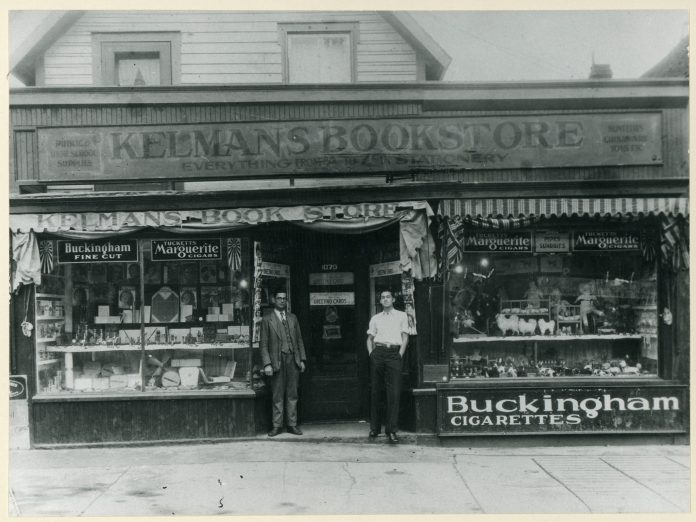

One of the permanent residents was Alex Kelman, who arrived in Hintonburg in 1920 with his wife Sylvia and young son Harry, and opened a books and general store at 1079 Wellington (now Taqueria La Bonita). This shop remained in operation until June of 1961 (the last six years as Kelman & Ritter, a women’s and teen’s clothing shop).

At the far east end of Hintonburg, where Wellington Street used to continue over the old train yards and stockyards at Ottawa West (as the Wellington Viaduct), a tall old 1889-built property stood at the northeast corner of Bayview and Wellington (now greenspace beyond the end of the Tom Brown Arena parking lot). In 1921, Jacob Taller opened a mattress-manufacturing plant (National Bedding), and moved his family (wife Ethel and ten children) upstairs. This factory would go on to produce a large number of the cot mattresses for Canada’s military in the Second World War, allowing the Tallers to retire comfortably in 1942.

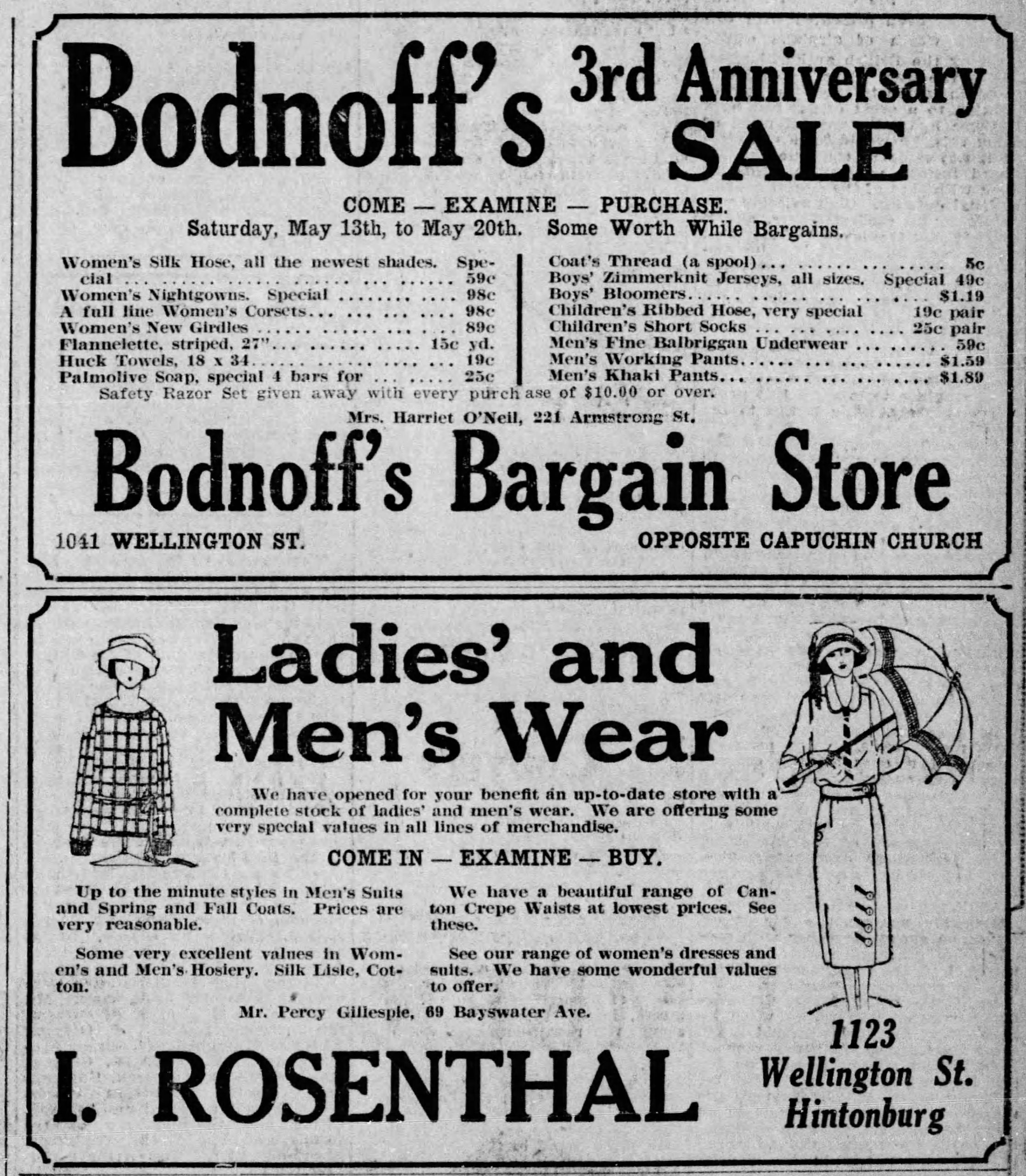

Benjamin Bodnoff’s brother Irving Bodnoff was just 20 years old when he opened “Bodnoff’s Bargain Store” at 1041 Wellington St. in 1919. He married Annie Rastovsky a year later, just weeks after she had emigrated from Russia (on their marriage certificate, she was listed with the unusual occupation of “electric shade maker”).

The other Jewish families to arrive between 1919-1921 included David Brill (electric supplies, 985 Wellington St.); Joseph Felberg (shoemaker, 987 Wellington St.); Philp Fogel (clothes cleaning, pressing and repair, 1015 Wellington St.); Henry Finklestein (bargain shop, 1065 Wellington St.); Abraham Kahan (boots and shoes, 1083 Wellington St. and later a second store at 987 Wellington St.); Roger Greenberg (grocery store, 1087 Wellington St.); Solomon S. Shuster (shoemaker, 1102 Wellington St.); and Hyman Adelson (resided at 1161 Wellington St.). Additionally, Israel Rosenthal (who was introduced in part one of the series), moved his business from Mechanicsville to 1123 Wellington St. in 1921.

Similarly, the resort hamlet of Britannia at the end of Ottawa’s streetcar line was equally a refuge for many of Ottawa’s Jewish residents. The 1921 census noted 11 Jewish families resident in summer homes at Britannia on census day (with another three families a little to the east in waterside cottages near Woodroffe and Westboro) – a who’s who of Ottawa’s prominent Jewish residents (including the Stein, Caplan, Freedman, Marks and Zivian families, to name a few).

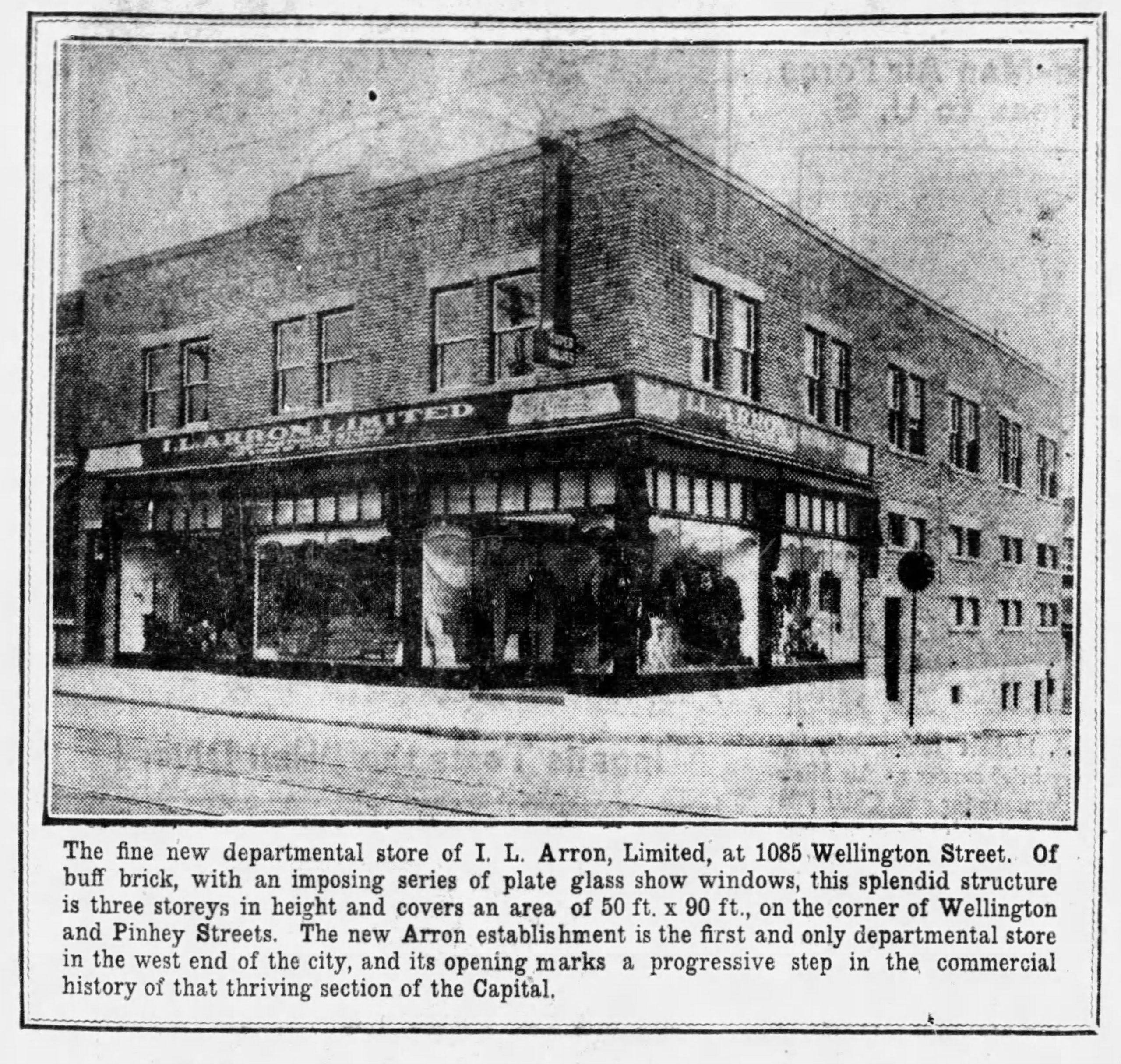

Notably, in 1923, Isidore Arron arrived in Hintonburg, establishing a clothing shop in rented quarters at 1020 Wellington St. In 1930, Arron brought substantial development to Hintonburg when he built the first department store west of downtown at 1085 Wellington St. (today’s Giant Tiger Express).

That same year (1930), Morris Zagerman established yards for his construction materials business at the corner of Bayview and Scott, which would remain in operation until sold to the NCC in 1975 (now the site of Merkley Supply).

The west-end Jewish community that sprung up quickly would remain close-knit. Frustrated with the need to travel into central Ottawa for services, the west-end residents began to meet in the Jacob Taller mattress factory for High Holy Day services, and at the Kelman and Blushinsky homes for daily and Shabbat services. This group became a permanent congregation in 1936, chartered under the name Agudath Israel. In 1938, they acquired the former St. Mathias Church at 17 Fairmont Ave., then moved to the former Methodist church at 30 Rosemount Ave. in 1949 before constructing a synagogue on Coldrey Avenue in 1966 – which is still the home of Kehillat Beth Israel today.

By the 1930s, the Jewish populations of Hintonburg and Westboro had increased significantly. However, immigration levels nearly reached a standstill. Canada’s Jewish population had risen from 16,000 in 1901 to 125,000 in 1921. But from 1923 to 1931, only 4,000 Jewish immigrants had been accepted annually, and just 4,000 in total between 1933 and 1939.

A dark hour in Canada’s history was its reluctance to take on Jewish refugees. Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King worried that Jewish immigration would “pollute Canada’s bloodstream.” Though accepting following the First World War, Canada had the worst record of any Western country in providing sanctuary to Jews of Europe in the 1930s and 1940s. Of the 800,000 Jews who had escaped Nazi Europe between 1933 and 1939, only the aforementioned 4,000 came to Canada.

After the First World War, a fundamental shift occurred in Canadian immigration, shifting from economic to ethnic criteria in judging the desirability of an immigrant. This stain in Canada’s history is tough to ignore.

Though life in Ontario was easier than other locales, there were still major struggles and restrictions. Educational institutions discriminated against Jewish applicants. Many industries would not hire Jews; and Jewish professionals such as engineers, architects, nurses and teachers had to hide their identity to find work in their fields. Legal firms would not hire Jewish lawyers, and there were no judges. Elsewhere in Ontario, many clubs, beaches and facilities advertised “Gentiles only,” but thankfully Ottawa seemed to have fewer such instances.

History shows that the neighbourhoods of west-end Ottawa were a welcoming place for Jewish people during an impossibly difficult era. These early families discussed in this two-part series found a new home here in Kitchissippi at a time when the need for one had never been greater. The community that developed as a result significantly influenced the way forward, laying the foundation for future generations of families to come, and ensuring Kitchissippi would remain a proud place to call home.