By Dave Allston

The Jewish community in Ottawa has a deep appreciation for its past, and the stories of the city’s first Jewish residents, businesses, schools and institutions are well researched and documented. Kitchissippi is home to the Ottawa Jewish Archives (located in the Soloway Jewish Community Centre on Nadolny Sachs Private), where photographs, documents and memories have been well preserved.

Less documented is the story of Kitchissippi’s first Jewish residents, and how a sizable, strong and lasting Jewish community sprung up almost overnight. Though, sadly, few Jews were immune to the horrible discrimination inflicted on those of their faith during the early decades of the 20th century, Kitchissippi was largely an early place of welcoming for those seeking refuge from worsening conditions elsewhere in the world.

This is the first part of a two-part series on the “early days” of Kitchissippi’s first Jewish residents, putting names and faces to these settler families and examining the factors and stories of what brought them to the neighbourhood.

Today, Kitchissippi is home to a large number of Jewish families, with census and survey data regularly showing one of the highest densities of Jewish citizens in the city. In the 2016 Census, for the question of “ethnic origin for the population in private households,” Kitchissippi Ward had the highest count of families who identified as Jewish.

So where did it all begin? Determining this was not easy: extensive research and digging through old tax assessment records, newspapers, directories and census pages yielded results which gradually pieced together the story.

Though Ottawa had a quickly growing Jewish population in the late 19th century, virtually all of Ottawa’s first Jewish people lived in Lowertown and the Byward Market. Early records show no Jews lived west of the Somerset Street Bridge until 1903.

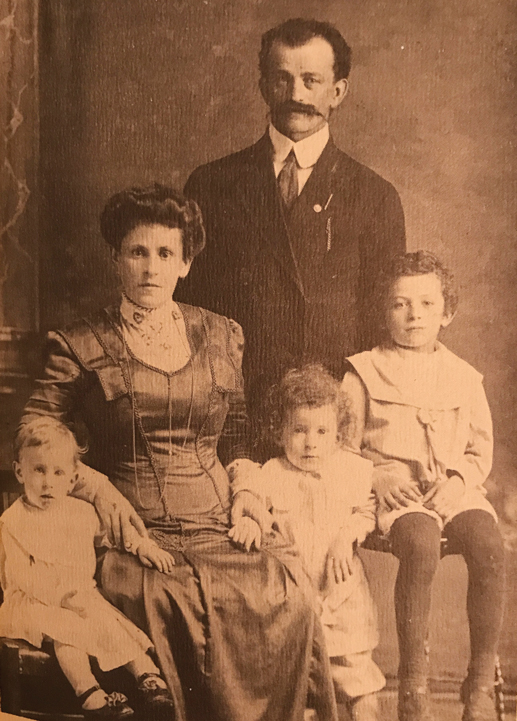

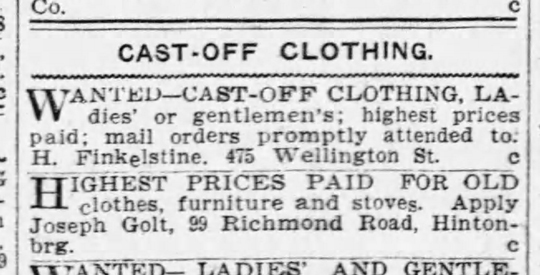

Joseph and Esther Golt had come to Canada around 1889 from Poland, first settling in Montreal before moving to Ottawa in the 1890s. By the time the family arrived in Hintonburg in June of 1903, they had four young children (adding three more soon after). Joseph opened a second-hand goods shop at 1081 Wellington St. W. (then known as 99 Richmond Rd.).

The life of a used-goods dealer, the small sizes of the spaces the Golts moved to and frequency of their moves (their shop and home moved four times in 11 years) likely meant years of battling poverty for the family – not to mention the discrimination experienced being the only Jews in the village. Within the first days of arriving in Hintonburg, Esther had an egg thrown in her eye, a case which ended up at County Police Court, and which the Ottawa Citizen made light of, referring to the egg as “decadent hen-fruit” in its coverage.

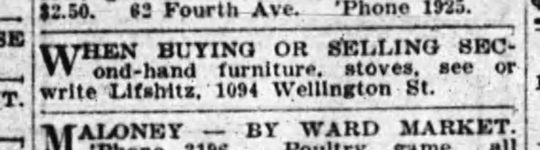

In 1907, Joseph leased the old general store on the southeast corner of Wellington and Sherbrooke (the site of Domino’s Pizza today) and briefly moved his shop there. Likely through his connections within Ottawa’s Jewish community, Joseph sold his shop and stock in 1908 to Bernard Lifshitz.

The story of the Lifshitz family (later modified to “Lieff”) is much better known, as their family rose to prominence in Ottawa over the years.

Bernard had brought his family to Canada only four years earlier, escaping anti-Semitic persecution in Poland by travelling to America in steerage, as many early Jewish immigrants had. He spent his first years in Canada working as a street peddler in Kingston briefly, then Lowertown Ottawa. The life of a peddler was not an easy one, and for those early immigrants taking on this type of work, it too was a life of poverty and hard work.

Street-corner or door-knocking peddlers were a common sight in Ottawa in that era, as it provided an opportunity for someone new to the city to make a living. Bernard was savvy, and realized that the market within Ottawa was saturated, and he could be more successful travelling throughout the outskirts of Ottawa, even on the Quebec side. As his son Abraham later wrote in his autobiography Gathering Rosebuds, “some were peddlers of rags, some of fruit and vegetables, others of kerosene and still others of notions. There were also peddlers who simply were called ‘customer peddlers.’ My father’s classification was ‘country peddler.’”

Perhaps prompting a change, peddlers were coming under fire at the time, as they were largely unregulated, and Ottawa retailers were upset that they only had to pay a small licence fee and no taxes.

Bernard purchased Joseph Golt’s business in Hintonburg, and moved with his wife Esther and two (soon to become four) young children to the tall, rough wood building on Wellington. Conditions were difficult. As Abraham Lieff later wrote: “In 1908 Hintonburg had just been annexed to the City of Ottawa, the streets were unpaved and often muddy, the sidewalks were wooden and the gas street lighting was inadequate. Our house had no indoor toilet and the sanitary facilities or ‘Shangri La’ were adjacent to the stable. We had running cold water in the house but no hot water heater.”

Regardless, for Bernard, operating a storefront was a step up from walking the country roads peddling. He also improved on the quality of goods the store offered. He made an agreement with Oliver’s (who produced furniture from their plant on Gladstone Avenue in Hintonburg) and sold new and nearly new furniture, tools, pots and pans and books. Abraham noted “most of our customers were English immigrants who were just settling in Hintonburg.”

Life was better, but still not easy, particularly for Esther.

“Raising four children, working hard in the store and being a valiant Jewish mother took its toll on mother,” wrote Abraham.

Esther’s 21-year-old brother Moses Palmer, who sold fruit as a peddler, presumably around Hintonburg, also resided in the home with his young wife and firstborn son.

The Lifshitz shop became a “port of call” to peddlers who door-knocked in Hintonburg. They would sell something at the door, take a deposit and then have the customer sign a card agreeing to pay the balance to the store. Then the peddler would return each week to collect a payment and perhaps sell more goods.

The Lifshitz family remained in Hintonburg only four years, and though the experience was largely a positive one, it wasn’t completely idyllic. Abraham wrote of some anti-Semitism he experienced in the neighbourhood.

“It was in Hintonburg where I first heard the words ‘Christ killer’ and ‘sheeny,’” he wrote, and also shared a story of an awful bullying incident by kids on Rosemount Avenue.

In 1912, the family decided to move back to the Byward Market, where Bernard became a teacher at the Ottawa Talmud Torah (where he would remain for 35 years). A red flag was nailed to the store, indicating that local auctioneer and real estate agent William Cole was to auction it. It was Cole’s continued misspelling on sales slips of the name Lifshitz as “Lieff” that resulted in the family adopting the new spelling.

Abraham went on to graduate from Osgoode Hall Law School in 1926, became the first Jewish Justice of the Supreme Court of Ontario and was known as the “Father of Ontario Family Law.” He lived to the age of 104, passing in 2007.

Kitchissippi’s third Jewish family was the Widder family, arriving in 1909. Max Widder had come to Ottawa that spring (by way of New York City, originally Hungary), and met his wife Mossie Niduvitch, daughter of a fruit seller. The couple married that summer, and moved into a small house at 77 Armstrong St. (demolished in 2017) where they opened a small grocery store for the neighbourhood. They were only briefly residents of Hintonburg, moving to California in December of 1911.

The 1911 Census mentions a fourth Jewish family in the vicinity, the Caplans. Caspar Caplan, who was 40 years old at the time, operated a small department store on Sussex Street, and would go on to establish Caplan’s department store on Rideau Street, which stood from 1916 to 1984. He resided with his family primarily at Britannia Bay for a few years, just beyond Kitchissippi’s borders, before permanently moving to Ottawa.

A large influx of Jewish residents would come at the close of the First World War (to be covered in part two) but just after Lifshitz and Widder left Hintonburg, 39-year-old Israel Rosenthal opened a grocery shop at 115 Carruthers St. in Mechanicsville in 1913, the start of a 30-year presence in the neighbourhood. He would be best remembered for his popular ladies’-and-men’s-wear shop at 1123 Wellington St. (1922-1943). While residing on Carruthers, the family took on a lodger, Harold Shoihet, whom daughter Lillian would marry, creating another well-known Ottawa Jewish family.

A little further west, 31-year-old Samuel Blushinsky opened a grocery store at 465 Parkdale Ave. in 1914, remaining in business there until the early 1930s. That same building continues to operate as a commercial spot today (Heartbreakers Pizza).

These early Jewish residents of Kitchissippi endured hardships but helped pave the way for the flood of Jewish refugees who would arrive to the area during and after WWI, settling in Hintonburg, Westboro and the neighbourhoods in between. Be sure to read part two in June for more of the story!