By Dave Allston

The closure and pending demolition of Webb’s Motel on Carling Avenue represents one of the final remnants of an important part of life in Kitchissippi that dates back to the 1860s. The history of main street accommodation for the traveller has played out in Kitchissippi as it has throughout North America. That era in our community is winding down as this area has transitioned from rural farmland to village to suburb to central core.

The story begins in 1864 when 64-year-old Joseph McGaw opened a small inn and tavern on the Richmond Road (where the Ottawa West Community Support building now stands, at Wellington and Carruthers). Though the village of Hintonburg had yet to take shape (or even to be named), Richmond Road — which had opened as a maintained toll road in 1853 — had grown in importance as a vital link for Ottawa to the west. In particular, rural farmers relied on it to bring their produce to the market. Having the “first” spot on the Road, as it approached Ottawa, was an advantage. For the tired and weary traveller, a farmer taking a break before going to market in the morning, or one caught in a rain or snow storm, the sight of McGaw’s inn would have been a welcome one, even if the accommodations were scant.

Seeing the value of the location, and the growth of the hamlet of future Hintonburg, Thomas G. Anderson and his associate William Taylor constructed a larger inn in 1867 at an even more optimal location: a one-acre site on the corner of Wellington and Parkdale (where the new Signature senior’s building is now under construction). Their “Farmer’s Hotel” caught the Richmond Road travellers from the west, as well as those from the south on the Merivale Road or Carling Avenue (then known as Manotick Street). While Hintonburg grew around it, the hotel enjoyed a successful 20 years of operation. It boasted a brick kitchen, spacious outhouses and stables and had expanded to 13 rooms at its peak. Meanwhile, McGaw’s inn remained in operation until his death in 1877.

Hintonburg then saw its hotel needs met by James Byers, who had managed the Farmers’ Hotel for three years before opening his own hotel, the “Hintonburg House.” It was located on Wellington Street across from the St. Francois D’Assise Church, included an incredible 27 rooms, and featured his even-more notable tavern. Byers put the Farmers’ Hotel out-of-business, as well as his competition from 1899-1909, Patrick Baxter’s “Britannia Hotel” at 959 Wellington (corner of Hilda), which also featured a tavern and billiards room. The Hintonburg House would remain in business until it shifted to a boarding house around 1912.

Mechanicsville also had a small tavern-hotel from 1889-1908, operated by Hyacinthe Latreille on Hinchey Avenue, near Emmerson, where it once intersected (now just NCC greenspace).

In the west, Westboro had its first hotel when Joseph Birch opened a large brick structure on the north-east corner of Richmond and Churchill in 1873. It was later run by John Burrows and Stephen Switzer, before becoming a commercial shop after the turn of the century, best known as Whitehorne’s Grocery for many years.

These inns were largely supported by their taverns. With the early-20th century push for controls on liquor, and outright prohibition, Carleton County began to issue fewer licenses. By the time prohibition kicked in, none of these hotels remained in operation.

Only a few small bed and breakfast type places were left, most notably the Wayside Inn on Richmond Road, at the foot of Wavell in McKellar Park, which operated from 1919 until 1959.

At the time, industrialization was transforming North American life. Changes in transportation altered how easily and quickly people travelled, leaving little need for hotels in suburban villages like Westboro and Hintonburg. Once prohibition was repealed, smaller taverns like the Carleton, Stirling and Elmdale opened, and most featured sleeping quarters upstairs. The Carleton offered rooms until as recently as the late 1970s.

However, it was the proliferation of automobiles and highways that led to the next big change. The world opened up to easier, more flexible travel. Many employees began receiving paid vacation benefits and the increase in middle class wealth led to a new industry: auto tourism.

Once again, the west end of Ottawa would find itself a prime location. The area offered accommodation to families coming into Ottawa for a vacation as the first motel options on their way, or simply a more affordable option to staying in pricey downtown hotels.

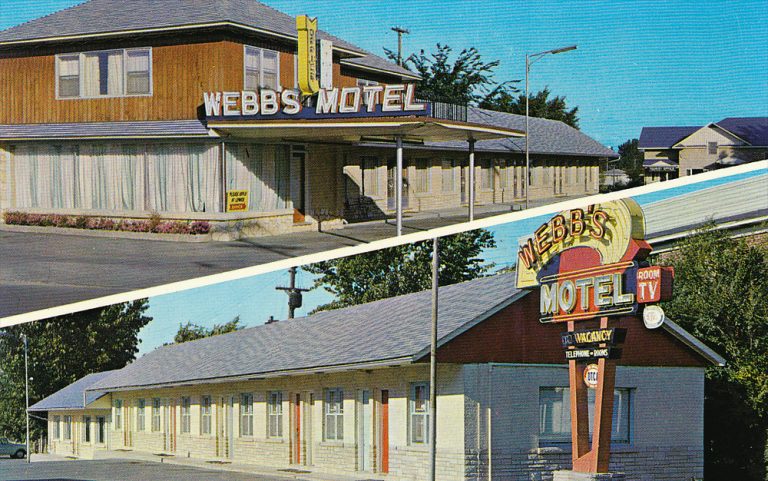

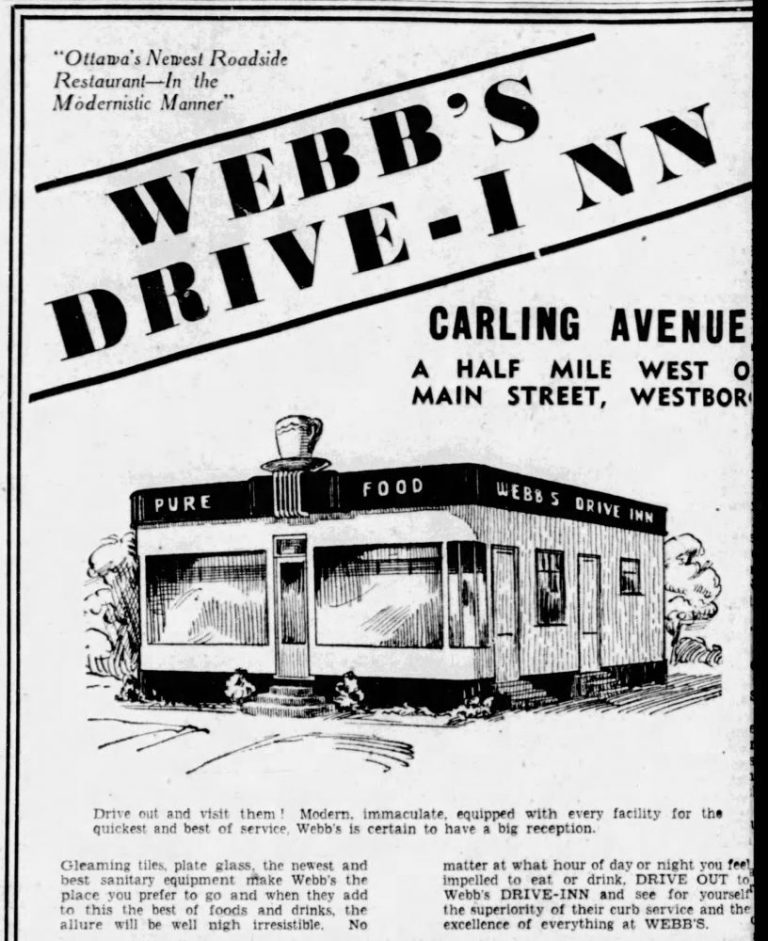

Richmond Road and Carling Avenue were still relatively sparse in the 1930s. Yet, traffic was increasing exponentially as Ottawa experienced a boom in tourism. Savvy entrepreneurs like Michael and Mary Macies, and Thomas and Olga Webb, had modest means and big dreams — they could see opportunity in auto tourism accommodations.

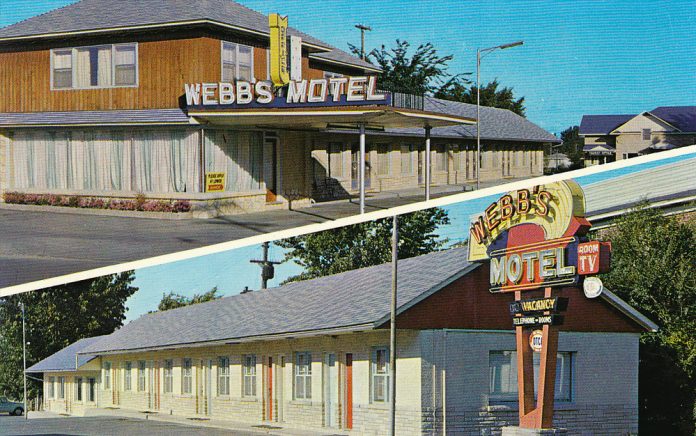

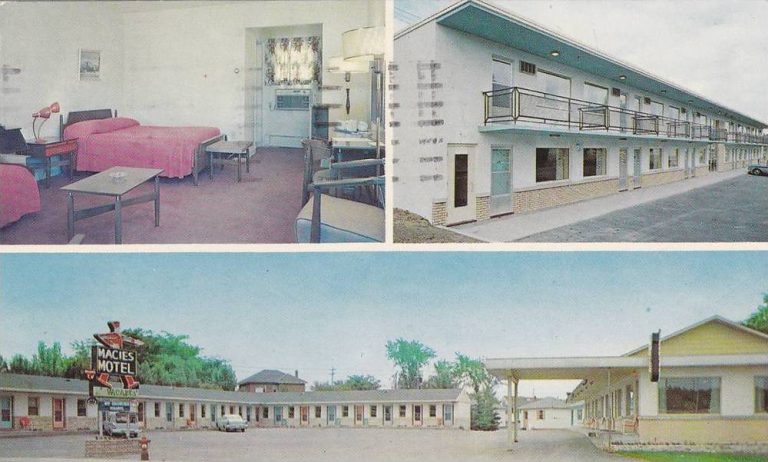

In 1939, both the Macies and Webbs acquired large chunks of land and began the gradual process of building their business through hard work. Both constructed small restaurants on their property in the summer of 1939, named Macies’ Barbecue (at Carling and Merivale) and Webb’s Drive Inn, respectively. Their growth would be almost in parallel: Soon after, both locations would add small cabins which would be rented on a nightly basis to travellers, and later add simple, long motel buildings. Eventually, the small cabins were replaced with larger motel blocks by the mid-1950s. Note that half of the Rose Bowl restaurant, which closed in the spring of 2019, was the original Webb’s Drive Inn; the original Macie’s Barbecue formed part of the Lucky Key, which was demolished in 2011.

Not far behind the Macies and Webbs was legendary west end figure Alex Dayton, who cut his teeth selling refreshments at Lansdowne Park sports events in the late 1930s and early 1940s. He opened a restaurant where Carling and Richmond intersect (where McDonalds and Shoppers Drug Mart stand today). Shortly after, Dayton expanded to offer motel and cabins as well, under the moniker Dayton’s Motel Villas (“Dayton’s Greet Where Hi-Ways Meet” was the business’s motto). It was later sold and renamed Town ‘N Country, existing until the late 1970s.

Tourist camps and auto courts were a symbol of the 1950s auto age. They were cheap, easily accessible and catered to automobile owners. Operating an on-site restaurant was a natural fit — it ensured additional business for the owners, and saved their clients from driving into town to get food or worse, bringing in hazardous equipment to cook meals in their rooms. The government was initially reluctant to issue alcohol permits to these locations, hurting business substantially, but the motor court owners banded together and had the restrictions changed.

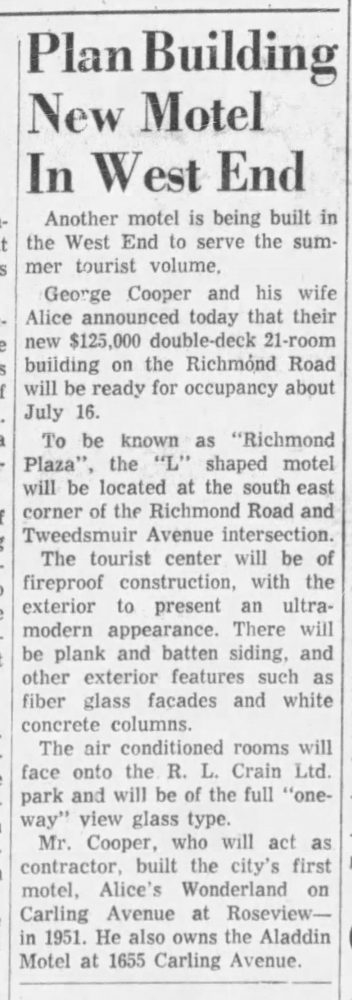

Another west end connection worth mentioning was that of George Cooper, a busy Ottawa builder who was involved in constructing some of Ottawa’s earliest subdivisions. He has the distinction of building Ottawa’s first motel, Alice’s Wonderland on Carling at Roseview, in 1952.

Cooper was also busy in Kitchissippi in the 1950s, constructing three motels: the Aladdin Motel on Carling just west of Churchill (1956), the Richmond Plaza on Richmond at Tweedsmuir (1958), and the Churchill Arms on Churchill just south of Carling (1959).

Ed Macies, son of Michael and Mary Macies spoke with me about the history of the Macies business (which he eventually took over), and also of the history of this evolving industry. The different local owners “were all fierce competitors, but also friends,” Ed said. And even family, in the case of the Webbs and Macies.

However, Ed added that “there was enough (business) to go around so we could all make a living.”

From the newspapers at the time, it seemed as though the owners needed to work together to improve the industry, which eventually led to the formation of the Greater Ottawa Motel Association.

In 1960, the industry began to experience its first major threat with the opening of the large Bruce MacDonald hotel on Carling Avenue, a new full-service location, the first outside of Centretown. This was followed by the $2-million Talisman Hotel next door in 1963. Once again, the industry had changed, and the smaller local motels had to adjust.

Fast forward fifty-plus years, Dayton’s is long gone, Webb’s is soon to go and even the Talisman is gone. Macies’ is now a Best Western and the Richmond Plaza remains as the last of George Cooper’s motels. Certainly, we are nearing the end of yet another chapter in the history of accommodations in Kitchissippi. I suppose the next chapter will be all about Airbnb?