By Ted Simpson –

Chris Martin came to Hintonburg looking to write a book on tattoos and found himself on both sides of the tattoo needle. He also found friends who’d change his life forever.

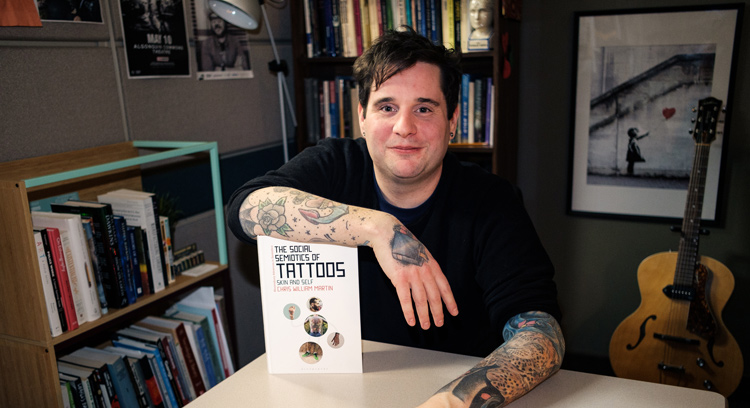

Chris is a sociologist, college professor, and the author of a new book that is based largely around daily life at Hintonburg’s Railbender Tattoo Studio.

The Social Semiotics of Tattoos: Skin and Self was several years in the making for Chris, and one of those years was spent doing deep research at Railbender in the style of an ethnography – in which an author immerses themselves as much as possible into a culture to understand every aspect of that culture.

Chris had already written about the meanings behind tattoos for his master’s thesis, but for his PhD, he was looking to go a little further. So he moved to Ottawa with his wife, and they settled in Hintonburg because they instantly loved the look and character of the neighbourhood.

At first, finding a studio that would agree to his project was proving difficult, but then he happened upon Railbender. It almost seems like it was destined to be.

“I was walking along Hamilton Avenue one day, and I stumbled across Railbender Tattoo Studio,” he described. “I looked up at the sign and it had a really cute font and it looked quite friendly, you don’t see that too much on tattoo studios, they’re usually quite gruff and quite intimidating in some way.”

After meeting with co-owner Alex Néron, Alex agreed to let Chris spend a couple of hours at the shop. As a strong friendship grew between the two of them, so did Chris’ involvement in the shop. He took on a roll of apprentice and was put to work cleaning and maintaining the high standard of the studio. Always with his notebook in hand, every aspect of daily life on the job went into Chris’ field notes.

You might have to read a bit between the lines of his book to recognize some local spots and characters, but they are all in there. “Everything has a fake name in the book, a pseudonym that provides anonymity,” says Chris. “It allows someone in Europe to read it and imagine their own tattoo studio down the road. Everyone has a fake name except for Alex, he became special.”(Sadly, Alex passed away peacefully on the evening of January 17, 2018, two-and-a-half years after a diagnosis of colorectal cancer.) In the book, Railbender became The Studio. Beyond The Pale was called Craft Beer House. Holland’s Cake and Shake became Armstrong’s Bake and Shake.

As much as he set out to write about tattoos, Chris says there is a lot of Hintonburg in his book.

“The neighbourhood really invites you in more than most. I ended up playing the Arts Park and The Happening as a musician… the neighbourhood just does a really good job of welcoming people,” he says.

When Chris first came to Railbender he had a few tattoos covering most of his arms from the elbow up, he’s now expanded that to cover all of his arms and onto his hands, he has work on his legs, chest and back. He even got a shot at doing one himself. “After a full year of apprenticeship-type training, they let me tattoo myself,” says Chris. “It’s not a great tattoo but it’s fun.”

Chris is hosting a book launch at Railbender on February 10 and copies will be available for purchase.

Hopefully, the book will assuage some of the curious folks he met along the way. “In all the time I was at Railbender a lot of people saw me with notebooks, a lot of them were curious what I was doing, what’s the culminating purpose of all of this.”

Tickets for the book launch will be limited. For details, see Railbender’s Facebook page at facebook.com/RailbenderStudio.

From The Social Semiotics of Tattoos: Skin and Self

Chapter 2. The Art and Artist Behind Your Tattoo

The dynamics of interaction

With every stroke of the needle, the tattoo artist permanently changes the appearance of a client’s body, and most often, his or her sense of self. I am sitting in a client’s chair getting tattooed at The Studio with the overwhelming buzz of the coil machine ringing in my ears; my heartbeat rising with anticipation; the intoxicating mixture of ink, blood, Dettol, and ointment in the air; and my breathing labored by pain. In this situation, I have often had an image of an older version of myself going about adult responsibilities and looking down on my inked skin and wondering–what I had done years ago, who I was, and most remarkably, what my research has meant to me. Meanwhile, the tattoo artist who is marking my skin may be filled with insecurity, uncertainty, frustration, excitement, pride, or a multitude of other possible emotions, but performing a version of self that exudes only confidence and assuredness. After all, each stroke of that needle is irreversible.