By Dave Allston –

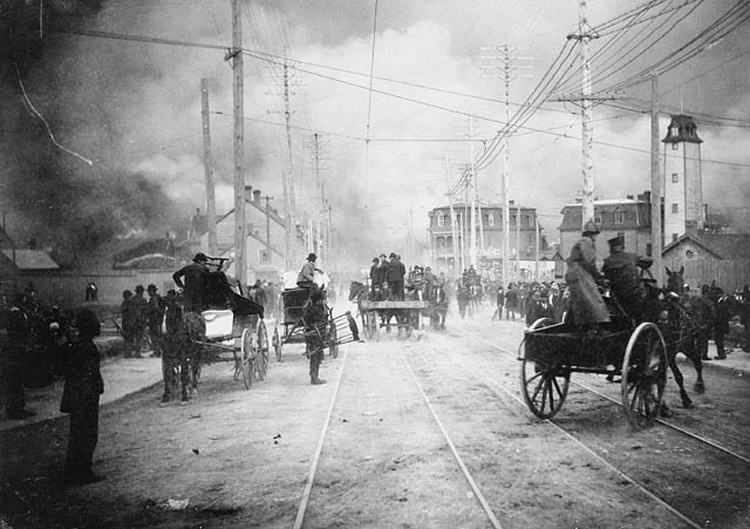

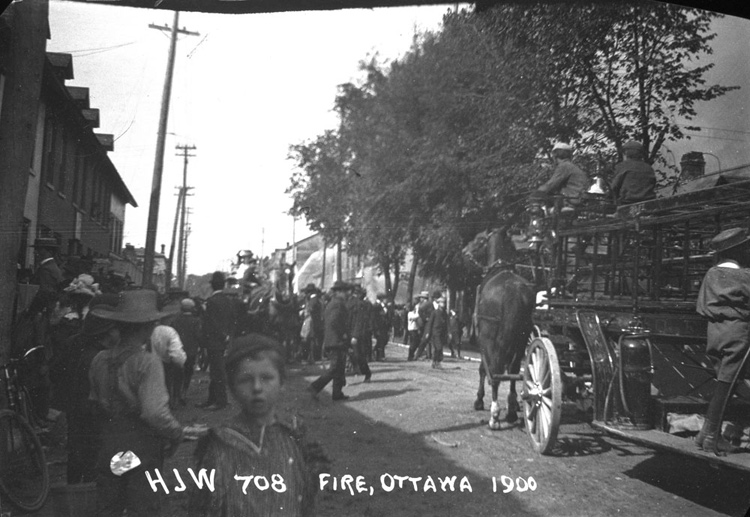

The early growth of Kitchissippi, and indeed Ottawa as a whole, was greatly influenced by a single event: the Great Fire of 1900. The fire nearly wiped out all of Hull, LeBreton Flats, and the neighbourhood between Booth and the O-Train line as far south as Dow’s Lake. It was pure luck (of the wind) that downtown Ottawa to the east and Hintonburg to the west was spared.

Following the fire, two key events occurred: first, an organized effort of a grand scale, the likes of which Canada had never been seen before, was required to help support the 15,000 homeless and destitute citizens. Second, communities like Hintonburg, which had ample affordable land available, became the new home for many of those displaced people.

The fire changed Ottawa. Though Ottawa had its share of poor and homeless prior to the fire, there were so many new people struggling that churches and other small organizations couldn’t handle the need.

Christmas 1900 and 1901 were bleak affairs for many. Each church did what they could to help but it became clear that a larger effort was required.

In 1902, the Ottawa Journal newspaper took it upon itself to ensure that Ottawa’s neediest, particularly children, were looked after at Christmas. Their pioneering initiative, which is now considered the first organized, large-scale Christmas cheer campaign in Ottawa collected money, clothes, toys, and food for distribution. This undertaking represented a fantastic amount of effort. Churches submitted names of those in need, and individuals could also apply anonymously. Each case was investigated by the Journal, not only to to ensure the individuals were deserving, but to customize the parcel to be delivered based on the number of children, their ages, and their wishes. Volunteers were recruited to assemble and deliver the parcels.

The pleas for assistance were published in the days up to Christmas. Many Kitchissippi families benefitted from the program. A Hintonburg widow wrote, “I have six small children, would be glad of anything.” Another letter stated, “Hearing yesterday that you were giving to the poor for Xmas, there is a little boy who has no one to keep him and he is in need. His mother is dead and his father went away and left him three months ago, and there has been no word from him. He is staying at [blank]. He has neither boots or clothes.”

Deliveries were made from morning until night on Christmas Eve: 52 parcels were distributed in Hull and 380 in Ottawa. Few wagons were available because every merchant in town was using them for their own deliveries, so sleighs were engaged to drop off neatly packed cardboard boxes containing food, candy, clothes, and toys.

A pair of boots was reported as a life-changing gift for a child because it meant they could attend school.

One delivery to Mechanicsville included a large parcel of clothing, toys and candy for a house in which two families were residing, one with nine children and the other with five. It must have been quite the sight. This is what the Journal observed: “the evidences of delight exhibited on the arrival of the gifts can be more easily imagined than described.”

On Pinhey Street, “…at a home where poverty in a marked degree was apparent,” a father received the parcel with “profuse expressions of gratitude. When the children became aware of what was in store for them – they did not take long to draw conclusions – they went wild with excitement.”

A Journal reporter, upon delivering a parcel to a home near Gladstone wrote: “Peeping through the door the reporter saw the whole family kneeling round the box and examining the contents amid tears and laughter. Such is one little instance of the way the gifts of the cheer fund where received and the good work it did in brightening the homes of many in Ottawa’s deserving poor.”

Families on Carleton Avenue, Parkdale Avenue and throughout Kitchissippi received much-appreciated parcels. One child gleefully remarked that Santa had returned for the first time since his father went out of work when the mills burned in 1900.

The program exposed just how severe the suffering of the poor was in many cases. An organized plan of relief work for those most in need was immediately organized and lists of the most pressing cases were given to charitable organizations. Thus began the first co-ordinated relief efforts for the needy, which continued to grow. Similar programs still run today, especially this time of year. Turn-of-the-century Kitchissippi was a difficult period for many, but thanks to the initiative of the Ottawa Journal and the generosity of so many Ottawa citizens and businesses, Christmas 1902 was likely remembered as a happy turning point for many.

Dave Allston is a local historian and the author of a blog called The Kitchissippi Museum. His family has lived in Kitchissippi for six generations. Do you have early memories to share? We’d love to hear them! Send your email to stories@kitchissippi.com.