Few forms of entertainment in the early 20th century were more popular than the travelling circus. A visit from touring companies such as Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey was often the highlight of the summer. Children waited for weeks in anticipation. One newspaper called it “the red letter day of all days in the calendar of youth.”

The entire production would surely have been an incredible sight. The logistical challenges they overcame are almost inconceivable. These tours were not small operations. An average circus comprised multiple trains with more than a thousand animals and an equal number of performers. They’d pull into town (even small communities between larger cities), set up in a few hours, put on a titanic-sized performance that drew everyone from the surrounding area, and be gone by the next morning.

Ottawa was relatively isolated but the large American circuses still managed regular visits during the 1800s and early 1900s. In fact, the first touring circus came to Bytown in August 1851, a remarkable accomplishment considering the area was still without rail service. By the turn of the century, the circus was an annual event.

The criteria for touring companies was simple. They required a large open area near railway tracks and in relative proximity to the population, ideally with close access to water. Lansdowne Park, and later the Glebe by Clemow Avenue, were the popular locations until the development of the Glebe required a new location in 1911. Two new sites came into common use: Plouffe Park and the future city yards just south of the Somerset Street bridge (which was known as Ottawa’s “circus grounds” for years), as well as the then-isolated area of Holland and Wellington, a spot which hosted three circuses from 1912 to 1914. (A previous Early Days column piqued the interest of many readers who wanted to learn more about these Kitchissippi-based circuses.)

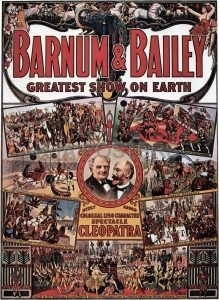

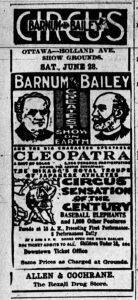

Ringling Brothers came to town in 1912 and 1914. In 1913, it was Barnum and Bailey (“The Greatest Show on Earth”). The circus arranged for the rental of the empty fields on the west side of Holland between Wellington and Byron months in advance. After weeks of promotion, the big day would finally arrive. It began overnight, with four trains containing over 100 cars arriving at LeBreton Flats to unload their contents, including the wagons which transported everything to Holland Avenue.

[Click images to enlarge]

That year, it was reported that “boss canvasman ‘Happy Jack’ Snellen and his horde of brawny followers” arrived with the chain-and-stake wagons to erect the 20-plus circus tents and teams of horses to pull the center poles upright. The cook tent was set up first, from which 5,000 meals were served each day. Other tents included the menagerie, with hundreds of exotic animals on display; the side shows, with “freaks” such as the bearded lady, three-headed man, and human pin cushion, and “deformities” including the “Toothless Minnehaha, the woman who has never smiled”); stables; a blacksmith, dressing rooms; wardrobe; barber; doctors, and dentists.

Local boys wandered the site and were often hired on the spot to help with set up. Their pay for their hard work? A free ticket to the show.

After set up, the entire cast assembled for a three-mile long parade that left Holland Avenue and went down Wellington all the way to Elgin Street and back, in time for the afternoon show at 2 p.m. (An evening show was held at 8 p.m.) The parade helped promote the circus and brought some excitement to the downtown streets on a weekday. Interestingly, road closures were not required, and streetcars simply followed the procession.

The touring cast included over 1,200 people, and the roster of animals included 500 horses, plus elephants, camels, giraffes, zebras, lions, a rhino, and a hippo.

The main event was held in a huge tent which measured 520’ x 280’. It was a three-ring circus, which meant a central show (“The Spectacle of Cleopatra” was the highlight of 1913), dancing (a ballet of 300 dancers, for example), six bands, and side shows, all happening at the same time. “So much going on at once that a great deal is missed in trying to see too much,” reported one newspaper. Special acts included a 17-year-old Australian girl performing horse tricks, jiu-jitsu demonstrations, and a baseball game played by elephants, seals, pigs, monkeys and a kangaroo. There were dozens of clowns and an array of gymnasts, acrobats, aerialists, and equilibrists.

The circus on Holland Avenue drew 45,000 people for the day’s performances. Then late that night, the team would deconstruct the site, and by daybreak, the circus would be gone without a trace.

After three successful summers on Holland, the arrival of WWI put a hold on circuses. By the time the war ended, the Holland-Wellington location was being sold for lots and no longer able to play host to the annual spectacle. Instead, Plouffe Park became Ottawa’s official circus site, and it remained so until 1939, when WWII signaled the end of the classic era of the travelling circus.

Dave Allston is a local historian and the author of a blog called The Kitchissippi Museum. His family has lived in Kitchissippi for six generations. Do you have memories of when the circus came to town? We’d love to hear them! Send your email to stories@kitchissippi.com.