Have you ever wondered what Kitchissippi would look like if we could go back in time? What would we see? What would be familiar? 1867 marked the unification of the Dominion of Canada, but it also marked the start of the neighbourhood’s transition from being purely rural. Soon trains would arrive, farms would become subdivisions, and industrialization would hasten changes in manufacturing, consumption, work and the urban landscape.

This special edition of “Early Days” will take you back to 1867 and bring to life our neighbourhood at that time; the people, the buildings, the way of life.

Life in 1867

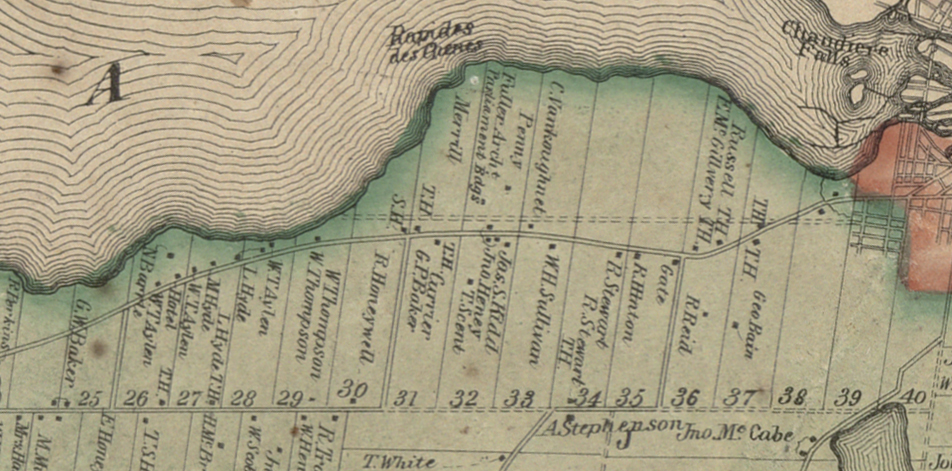

There were less than 50 houses in all of Kitchissippi and the population numbered about 220. (To compare, the Kitchissippi of 2017 has 21,000 households and a population of 44,000!) The entire ward was in Nepean Township, still relatively new itself (the first settlers having arrived in 1811). Most residents emigrated from Ireland, Scotland or England and the vast majority of them farmed. A rare few ‘commuting’ Ottawans built here for the tranquility. Farm properties were long, thin parcels of land that typically stretched from the Ottawa River to Carling Avenue, but were only about five modern city blocks wide.

There was only one road that cut through Kitchissippi – Richmond Road – and it was the lifeline to civilization. It had been macadamized in 1853 with compacted crushed stone, and operated as a toll road from Parkdale to Bells Corners. Only three other official roads existed, all running off Richmond: sideline roads at Woodroffe, Churchill and Parkdale.

There were no trains through the area. The first would arrive in 1870. Everyone travelled by horse or by foot. There were no merchants or industry. Electricity, telephone, water service (except for wells) and sewer were still many years off. The settlement didn’t even have a doctor close by.

Take a tour through Kitchissippi, as a time traveller

Let’s climb into our time machine and set the dial back 150 years. Before we arrive, do note that modern day street names and reference points have been added to the following text in [square brackets] so we can better situate ourselves in today’s landscape.

Let’s begin at Woodroffe Avenue, circa 1867. Take a good look around. There is not a single house on the south side of Richmond Road all the way to Churchill. In fact, it’s just miles of farmland, fences and the occasional barn or outbuilding. At this point in time, homes are built on the north side of Richmond, closer to the river.

The first dwelling you’ll see is a 1.5-storey log home on Richmond Road owned by the Thomson family [at Lockhart Avenue], but a bit closer to the water is the property of Nicholas Barrie, who also owns the popular two storey log inn and tavern on Richmond Road [the Lord Richmond Apartments]. Barrie’s tavern, run by Irishman Thomas Kennedy, is not designed for tourists, but for travelling farmers and area labourers, but maybe if you’re really thirsty (and don’t stand out too much in your modern day clothing) they’ll serve you a pint and let you wet your whistle.

Let’s keep walking east. We see two farms, belonging to brothers Mason and Leonard Hyde. Both have log houses, though Mason’s is far larger and also functions as an inn. Leonard’s farm will be the site of a notable event in August 1868, when the groundbreaking ceremony for the new Canada Central Railway will be held at the rear of his farm [Courtney Avenue if it ran north to the river].

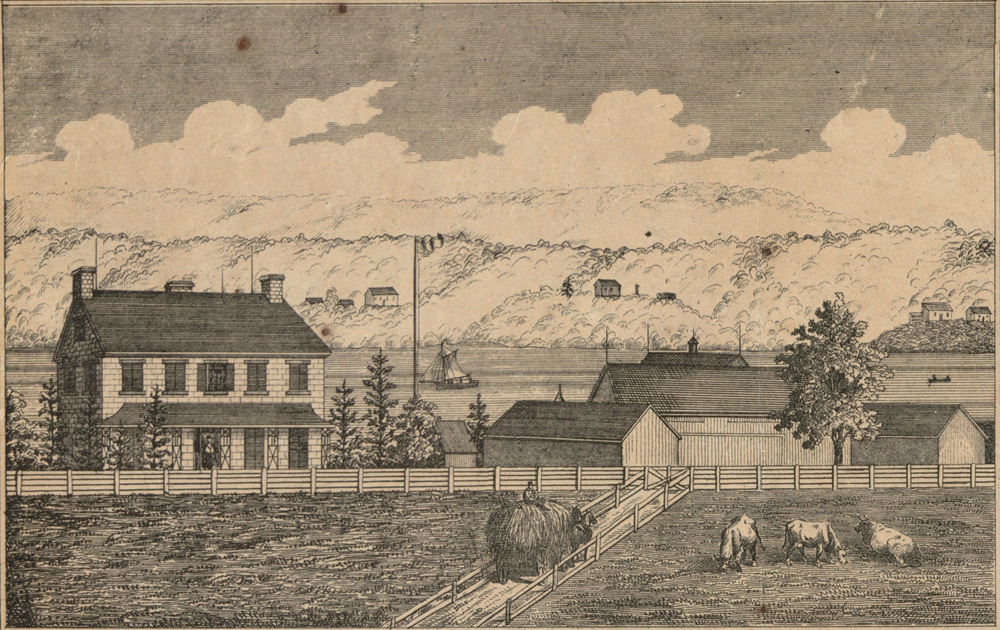

We then come upon the first familiar sight, as least to the modern time traveller because it still stands: the “McKellar-Bingham” house [located at the foot of Windermere Avenue]. Constructed by John Thomson around 1840, Kitchissippi residents of 1867 will tell you the farm is maintained by his nephew Willam Aylen; a massive 450-acre operation with 35 cows, 80 sheep, eight pigs and four horses. He had sold the farm the year before to Andrew Pritchard, but was allowed to continue to use the land. Pritchard will later sell to Archibald McKellar in 1873.

A little further is the Thomson family’s home, called Maplelawn. [It’s still called Maplelawn in 2017, and it’s the location of Keg Manor.] It was built in 1831, but since we’re dropping by in 1867, we find 13 people living there, and no steakhouse. At this time, the Thomson family own 40 cows and 14 horses, but are suffering financially and have the property up for sale. 1867 will end on a sad note when William Thomson passes away on December 27 at the age of 76.

Next in succession we see another small Thomson house; a grand villa, newly built by the Surveyor of Customs in Ottawa, Major Archibald Douglas [Dominion Avenue]; the home of carpenter Robert Mather; the two-year-old All Saints Church, built in the middle of the wilderness to serve the farms of Nepean; and finally, the new brick schoolhouse for ‘School Section 2’ [corner of Richmond and Churchill where Gezellig is located] built the year before to replace the original, and rustic, 1851 school. The School Master is Robert Whillans.

Crossing Churchill, the Birch family log home, “The Ovens,” can be seen on the right. It’s the first house on the south side of Richmond [between Eden and Edgewood Avenues]. The Birch family are pioneers dating back to 1838.

Moving eastward, we come to a more developed area. Robert Hardy constructed a small home where the School Master (or Mistress) would live [Otto’s]. Just next to it is the house and shop of Scottish blacksmith, William Archibald. Well behind it is a modest house [the recently closed location of Trailhead at McRae] on a five acre plot of land farmed by 65-year old John Sharp. Set even further back is a grand two storey frame house [Metropole] belonging to Ottawa architect Thomas Fuller, who, the year before in 1866, completed his most famous project, Ottawa’s Parliament buildings. A smaller house can be seen towards the river [Remic at Premier] on a large parcel of land owned by Charles Pinhey, son of Pinhey’s Point founder, Hamnett Pinhey.

There is hardly a house north of future Scott Street. Interestingly, there is little development along the river. Traces of the original paths of the Algonquins and the original Richmond Road are visible but the land east of Churchill is used for hunting and stockyards.

Back up to Richmond Road is the stone “Syringa Cottage” on “Buffalo” John Heney’s property [Canadian Bank Note], across from the old stone “Aylen-Heney House” which will still be standing in 2017 [Kirkwood]. The Heney farm contains several other buildings including a small house that is set well back from the road [Wesley at Dawson].

Beyond this point, we reenter farmland owned by noteworthy pioneer families of Kitchissippi. Hon. James Skead, who is three years away from opening a major steam saw mill at the beach, ultimately creating Westboro, has been investing in Kitchissippi land since 1859. In 1867, Skead owns nearly 300 acres. A small house on his property [Hilson] is rented to tenants.

Next is “The Elms,” or as it will later be known, The Convent. Built about six years before, a visitor to 1867 would learn former Buckingham lumberman George W. Eaton, occupies it with his family of 14!

Across Richmond is the “Manor House” [Mailes and Patricia], which will find a new owner as the calendar turns to 1868: Captain Daniel Keyworth Cowley.

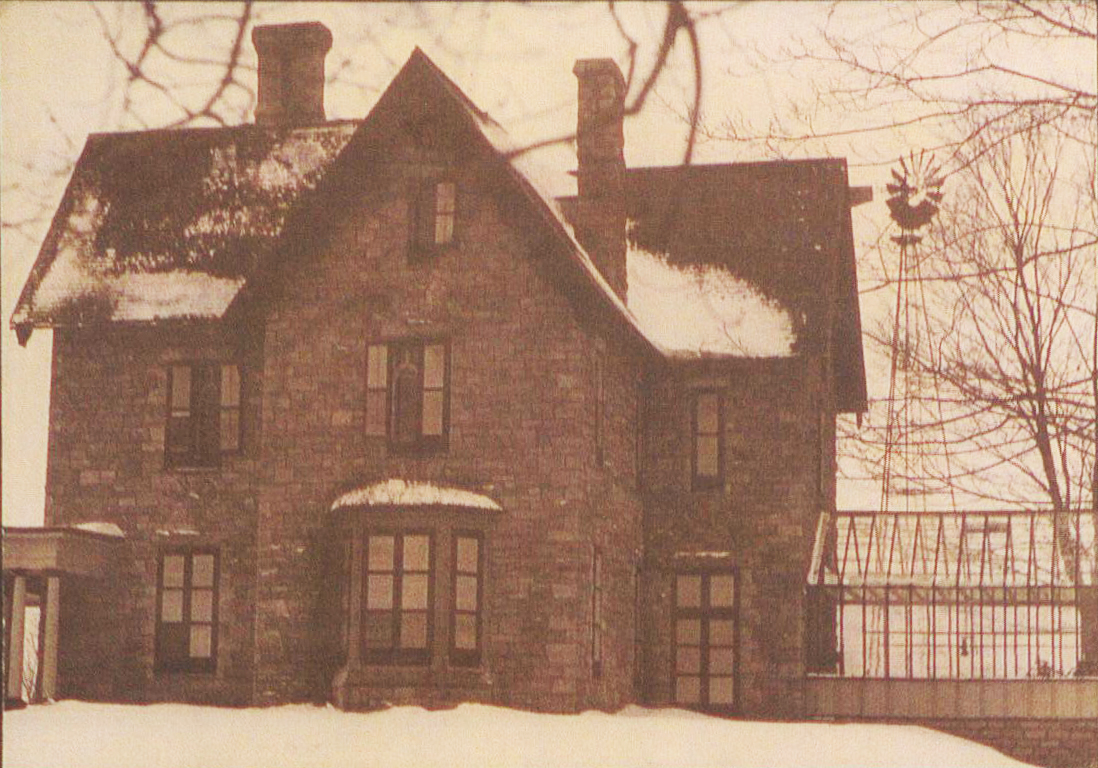

Moving east is the Roderick Stewart farm, which is also known for its popular shooting range. Their amazing stone house, built in 1832, will be tragically and senselessly demolished in 1961 [Julian Avenue].

Well south of Richmond Road is thickly wooded forest [past Iona]. The land by the river in this area has been owned by recently deceased Ruggles Wright, son of Philemon Wright, the founder of Hull. In 1867, one small house stands here, occupied by widow Anastasia Britt [Northwestern].

The framed Hinton farmhouse [Holland at Byron] is home to Robert Hinton and his family. Robert’s father Joseph relocated from Richmond in 1867 and will make significant contributions to the growing community, helping establish the post office and grammar school, and donating land for the Nepean Town Hall. In 1879, the village will be named Hintonburg in his honour.

At the river’s edge is the old 1840s Nicholas Sparks mill [north end of Parkdale], which, in 1867 has been long closed though some of its buildings and worker houses still stand [Parkway off-ramp]. This area largely consists of cultivated fields.

At Parkdale Avenue is the eastern tollhouse for Richmond Road, operated 24/7 by James Fenton. Travellers pay a toll based on their destination, number of horses, vehicles, and the time of year. These tolls pay for the maintenance of Richmond Road.

Moving east, the Richmond Road of 1867 gets busy again. In immediate succession on the south side is John Anderson’s relatively new, brick “Farmer’s Hotel,” Richard Bishop’s stone house (which will later become the home of village doctor, I. G. Smith), the white frame home of future Carleton County Judge William A. Ross [behind Grace Manor], and Sparks Street bookseller John Durie’s landmark home “The Lindens” [Melrose]. (Click photos to enlarge.)

Further south from Richmond, in quiet isolation, are the stone houses of Scottish friends Robert Reid [Reid Park] and George Bayne [Fuller Street], who arrived from Scotland on the same boat in 1827. In 1867, Reid’s stone house is the only three storey home in all of Kitchissippi (and will survive until its tragic demolition in 2017).

On the north side of Richmond at Parkdale is the old square stone home of retired military man Donald Grant (for whom the street behind would later be named), another Grant-owned house, James Fitzgibbon’s frame house (which exists in 2017 as one section of the Holy Rosary Church), and finally the elderly Joseph McGaw’s “Cave Creek Hotel” [Carruthers]. McGaw’s is more tavern than inn, due to its meager stabling facilities. As a visitor in 1867, you’d quickly find out that travelling farmers care more for the proper housing of their horses than they do the quality of the food or rooms.

There is a series of creeks and caves in this area which will later be dynamited for fear of collapse. A major cave running underneath the future Rosemount and Carruthers is a delight for children of the era. Beyond this point is only Judge Armstrong’s “Richmond Lodge,” [Garland] which still stands in 2017. East towards Ottawa is still sparsely developed, with open fields to the river. Mechanicsville won’t exist for another five years, but when the railway arrives this entire area will boom, commencing a new era of Kitchissippi history.

Dave Allston is a local historian and the author of a blog called The Kitchissippi Museum. His family has lived in Kitchissippi for six generations. Do you have early memories of the area? We’d love to hear them! Send your email to stories@kitchissippi.com.