Medical professionals sometimes refer to the “pillars” of cancer treatment. Until recently there have been four pillars: surgery, radiotherapy, traditional chemotherapy, and precision therapy. For thousands of years, surgery was the only pillar supporting cancer care. Radiotherapy, or radiation therapy, which uses high-energy particles to destroy cancer cells became a second pillar in the late 1800s. The third pillar, chemotherapy, was first explored in the 1940s when a derivative of nitrogen mustard gas was tested as a treatment for lymphoma. Precision therapy, which uses drugs or other substances to more precisely identify, target, and attack cancer cells, was added as a fourth pillar in the 1990s. Today, a fifth pillar is being added to support cancer treatment: immunotherapy.

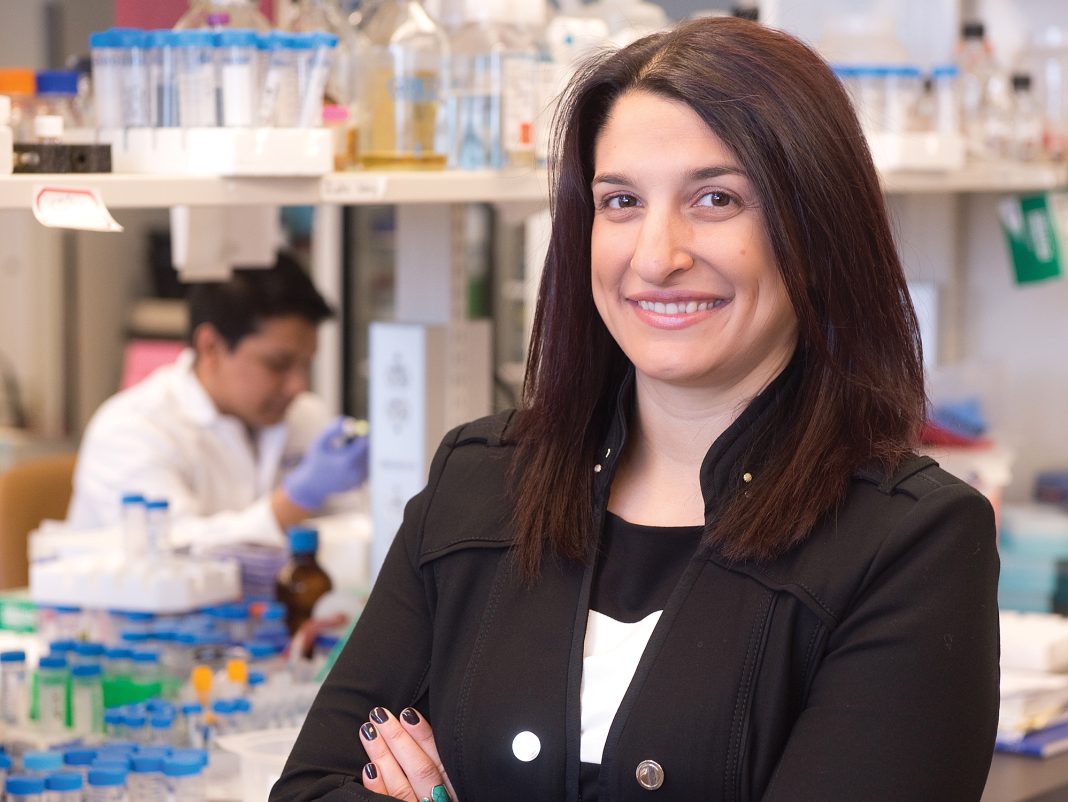

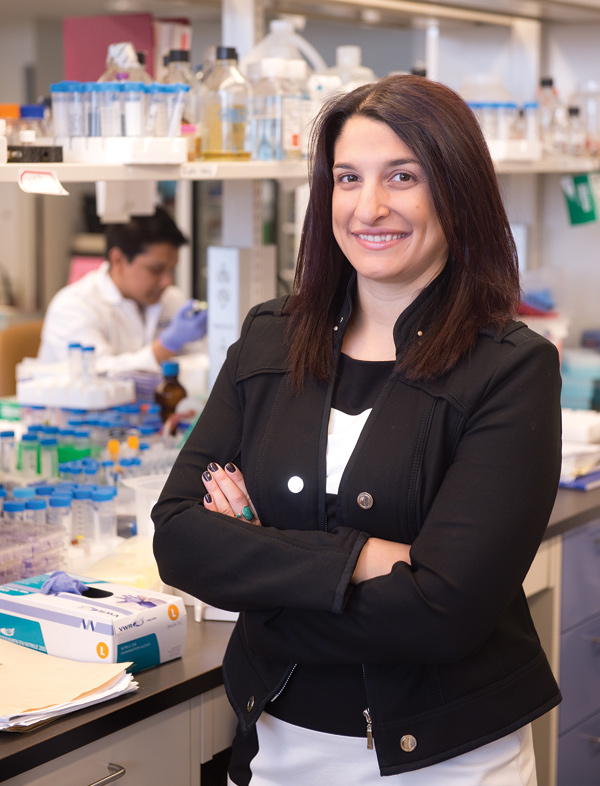

Dr. Natasha Kekre is a hematologist in the Blood and Marrow Transplant Program, and an associate scientist at The Ottawa Hospital. She is also an assistant professor in the Department of Medicine at the University of Ottawa.

Dr. Kekre is part of a team that is bringing the next generation of treatment to cancer patients.

For regular folks with little medical experience, cancer immunotherapy may sound like something from a sci-fi novel. It refers to a treatment that uses patients’ own immune cells to cure their cancer. There are different kinds of immunotherapies, but Dr. Kekre’s research involves using T-cells to fight certain types of leukemia and lymphoma, which are cancers of the blood.

T-cells are a type of white blood cell that play a critical role in the immune system. T-cells originate in bone marrow, and one of their jobs is to attack foreign invaders and infected cells, like tumour cells. The “killer” T-cell is equipped with receptors that can latch on to these invaders. It’s a very unique search and destroy mission. Put simply, imagine a T-cell receptor as a specialized Lego piece that can only fit into one shape of invader Lego. Once those pieces connect, the invader is toast.

Research has shown that some cancers, such as acute leukemia, can be treated by the implementation of genetically modified tumour-killing immune cells: powerful “Superhero cells.” In this particular therapy, T-cells are removed from the patient’s blood, are modified in a laboratory, and grown in large numbers.

“We manipulate those immune cells from a patient and think that if they were modified in the right way they could attack the tumour cells,” explains Dr. Kekre. “So we take them out of a patient, and we try to re-engineer them so that they express a certain receptor on their surface that allows them to specifically activate and attack the tumour cells. We call that chimeric antigen receptor T-Cells; CAR-T cells.”

The CAR-T cells are injected back into the patient. If all goes well, they’ll use their specially engineered receptors to identify and destroy cancer cells that have the matching antigen (a.k.a. that Lego piece).

Dr. Kekre is quick to point out that this is not exactly new medicine. Some patients with advanced acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and some types of lymphoma in the U.S. have had their cancer disappear in early immunotherapy trials. These treatments are not, however, readily available in Canada.

Dr. Kekre and her team are creating a system in which they can create an affordable plan for CAR-T cells. The hope is to begin clinical trials here in Ottawa and offer this option to patients with specific cancers within the next few years.

“We come from a very public health care system where we believe in access to care for all of our patients, and I think that it fits within our duty to provide that to patients,” says Dr. Kekre. “So the bottom line is that this protocol, this system, is going to build on research we already have in the U.S. To actually get access to patients – that’s the first part of this. We’re building a Canadian platform, and this will go across Canada, not just Ottawa.”

Could this immunotherapy spell the end of conventional treatments? If so, what happens to the other pillars? Although these advances are very real and exciting, more research is needed before immunotherapy is readily available to cancer patients. Clinical trials need to be a part of this as well, and that takes time. No one knows how immunotherapy will play into the current standard of care, but the hope is that it will become another line of therapy available to patients and open up an option that wasn’t available before.

“For example, right now, if patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia relapse after a stem cell transplant, their survival can be quite dismal and we need better options for them,” says Dr. Kekre. Whether this particular therapy will replace bone marrow transplants – the conventional treatment for acute leukemia – is still to be seen.

It’s a unique initiative and a special collaboration with researchers and medical professionals; a real made-in-Ottawa approach.

“We’re trying to provide, not just a new strategy of killing tumour cells and a new care for patients, but we’re actually bringing together scientists and physicians from all over Canada to build this exciting initiative,” says Dr. Kekre. “Our current number one priority is access to care for patients in Canada who would benefit from these therapies, and I think that’s what makes us uniquely Canadian. But also, it’s a different priority than if you’re just trying to test out a new therapy that’s never been tested before.

“I think that’s what makes this different from anything I’ve seen, in this landscape, in the world right now.”