On the road to Lemieux Island, just off the SJAM Parkway, lies the mysterious ruins of a structure which has sat untouched and decaying for nearly thirty years. A popular spot for urban explorers and bored youths alike, this unmarked derelict site has an important history that is intrinsically tied to Hintonburg’s early development.

Hintonburg became independent from Nepean Township in 1893, chiefly over the desire to allow streetcars along Richmond Road. Having accomplished that, the fast-growing village set its next infrastructure goal as the establishment of water service. Until the late 1890s, the west end was entirely without water for fire protection, manufacturing or domestic use.

Throughout the decade there were endless plans, surveys and negotiations, but none were financially or realistically viable. A contract to build a system for Hintonburg was eventually awarded to Edward J. Rainboth and his Ottawa Suburban Waterworks Company in 1898. Rainboth barely got the work started, defaulted, and the matter ended up in court.

Renowned engineer Charles H. Keefer was hired by village council in January 1899 to lead the project. Keefer drew up new specifications and oversaw the tendering process. 30 applications were received from companies across North America for the labour (excavation and pipelaying) and materials (cast iron pipes, valves, hydrants). H. B. Merrill of Ottawa was contracted for two pumping engines and two boilers (at a cost of $4,350), while the firm of Cowan and Doran of Ottawa were hired to construct the pumping station ($4,435) to house them.

When work began on May 1, 1899, the first task for the large gang of Hintonburg men employed on the job was the pumphouse foundation. Its site near the Ottawa River was carefully chosen, keeping in mind water quality and flood prevention for the station. James Newton, instrumental in bringing waterworks to Hintonburg, resigned from village council to become the first pumphouse engineer.

By the end of September, the pumphouse was complete, housing the boilers and two pumps with a joint capacity of 1,500 gallons per minute. The building was one-and-a-half storeys of cut limestone with a pitched roof with cedar shingles. There was a circular turret with a conical roof and unique arched half-circle windows on the north and south facades. The original structure also featured a tall brick chimney on the south side to fire the boilers.

The summer of 1899 was filled with excitement for Hintonburg residents. Over the space of six months, the entire village was dug up (with much blasting required to obtain the required 7’ depth for the pipes). Streets were unusable, the noise was intolerable, yet few complained. Water distribution would make life significantly easier and real estate values were exploding. Hintonburg could also establish its first fire brigade.

On November 27, 1899, water flowed to the houses and businesses of Hintonburg for the first time. It represented a significant convenience, even though the water was unfiltered and untreated.

Hintonburg joined the city of Ottawa in 1907, largely due to their requirement for a sewer system. Despite their urgent need, they were still paying off the debt incurred establishing the waterworks. Ottawa would regret dragging their feet on the Hintonburg sewage issue. Typhoid epidemics hit Ottawa in 1911 and 1912 due to untreated waste.

Hintonburg eventually connected to the city water supply and the pumphouse was gradually phased out. It closed briefly in 1912 and was last used in 1916 while the overland pipe system was installed from Lemieux Island.

The vacant building almost became a branch of the Ottawa library but lost out to Rosemount Avenue. Instead, the old pumphouse was used for city storage for nearly a decade.

In 1924, the building was turned into a residence and gatehouse for Lemieux Island. The tall brick chimney was demolished, temporary storage sheds were removed, verandahs were constructed on the south and east facades and four wooden posts were added to the bellcast eaves of the steep roof. The large living room overlooked the water while the rear portion of the house featured a tiny kitchen, dining room, bathroom and bedroom. A staircase from the living room went upstairs to a sizeable second bedroom.

Robert Preston Moodie (grandson and namesake of the early Bells Corners settler) was superintendent of the Lemieux Island plant. Robert and family were its first occupants. The family of Caradoc Clarke were its next residents. Caradoc was also superintendent (the first for the new Lemieux Island filtration plant when it opened in mid-April 1932). In an 1988 letter, his daughter Lynn reminisced about the house she still considered home: “If walls could talk, many good parties were held there as both our Mom and Dad entertained in the lovely living room. My favourite room was the one with the turret, as I could see miles of Ottawa from it. We skated on the river and picnicked on the small island half way over the bridge, pretending we were marooned.”

Carden Heeney, Deputy Commissioner (later Commissioner) of Waterworks, was its longest occupant, residing there from 1935 until his death in 1980. The City chose not to rent out the house afterward and it sat vacant for several years.

The building received heritage designation in 1987 due to its industrial significance, its role in Hintonburg’s development, and for its architectural value as an “attractive Victorian delight.” In 1988 it was rezoned Heritage Commercial and nearly repurposed as a restaurant.

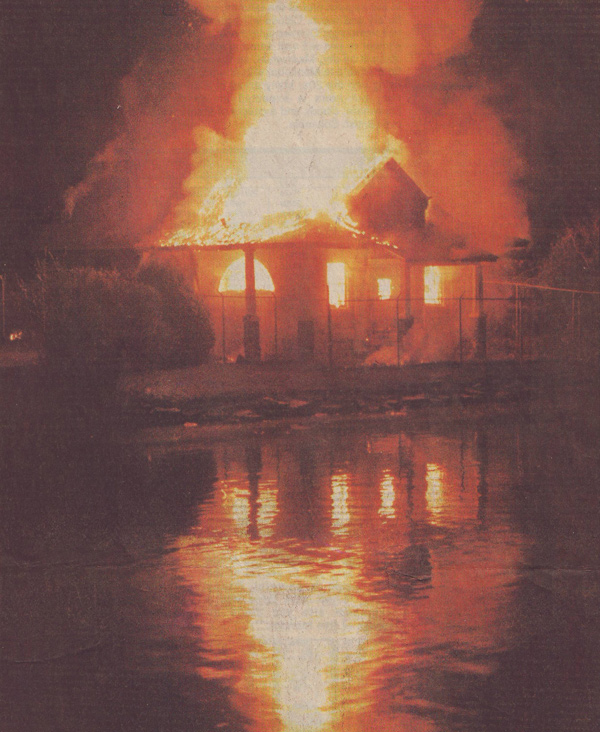

After a small fire was set in 1987, a chain link fence was installed. However, in the early morning hours of May 8, 1989, fire ravaged the building. Though significantly damaged, the building was still in salvageable condition.

Since 1989, the building has been left to deteriorate. It has been open to the elements for nearly 30 years. The property is tragically under utilized and desperately needs a proposal that would take advantage of this scenic and historic site. Stabilization and restoration, at least in part, is still a possibility, though, realistically, time is running out for the City of Ottawa to rescue even a portion of this important piece of local history.