Dr. Lauralyn McIntyre is a Senior Scientist in the Clinical Epidemiology Program and a physician in Critical Care at The Ottawa Hospital. She is also an Associate Professor in the Department of Medicine at the University of Ottawa. One main area of interest ties all of these together: septic shock.

Although septic shock is a serious medical condition that has been portrayed on countless medical dramas, it isn’t widely understood. Sepsis refers to a body’s response to a serious infection and can manifest itself in many different ways. The “new” definition refers to a serious infection and at least one dysfunctional organ. This could be your brain, lungs, kidneys, or bone marrow – and it could happen to anyone – especially individuals with chronic diseases or suppressed immune systems. If symptoms include low blood pressure, it’s called septic shock and carries with it a high mortality rate and risk of long-term complications for those who survive.

Over time, the medical community has made some improvements in patient outcomes with better identification, resuscitation, and antibiotics. Survivors, however, are often faced with serious long-term issues including psychological and post-traumatic distress, physical weakness, and depression.

“It goes on and on,” describes Dr. McIntyre. “It has a huge burden of illness, both from the perspective of death and even for the people who survive it.”

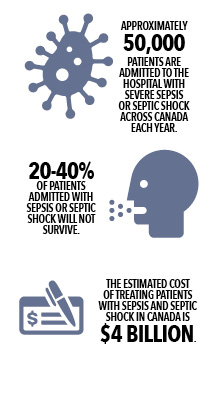

In Canada, approximately 50,000 patients every year are admitted to hospitals with sepsis or septic shock and 20 to 40 per cent of those patients will die. Dr. McIntyre estimates that sepsis and septic shock account for about 20 per cent of admissions to the ICU at The Ottawa Hospital.

In Canada, approximately 50,000 patients every year are admitted to hospitals with sepsis or septic shock and 20 to 40 per cent of those patients will die. Dr. McIntyre estimates that sepsis and septic shock account for about 20 per cent of admissions to the ICU at The Ottawa Hospital.

Sepsis and septic shock represent an enormous challenge to patients, to the health care system, and to the caregivers who look after patients after they leave the hospital.

Dr. McIntyre and her colleague Dr. Duncan Stewart, saw a big challenge and lots of room for potential. And that’s where stem cells come in. They have been part of a team of specialists who’ve spent the last five or six years working towards conducting a phase one trial to treat septic shock using stem cells.

“The type of stem cells that we’re studying for the treatment of septic shock is completely novel and highly experimental, and has great potential to help patients,” says Dr. McIntyre.

Early research in animal models showed stem cells reduce death in animals with sepsis by calming the immune system, restoring organ function and clearing the pathogens faster from the system.

In the phase one trial, medical staff tested stem cell treatment in a small subset of patients with septic shock. They were looking at the tolerability of cells and trying to determine the best dose to use in a subsequent randomized control trial.

That first phase was completed in June and it was a success. It was the first clinical trial of its kind in the world.

“The cells were very well tolerated and that has given our team the impetus, the rationale, and the motivation, to go forward to a much larger study, which will be a randomized study,” says Dr. McIntyre.

The cells at the centre of the study are stem cells that come from the bone marrow of healthy volunteers who donated their marrow for this clinical trial.

When researchers originally isolated stem cells, they thought they supported blood and the bone marrow. Scientists eventually discovered these cells have a great ability to modulate inflammation. “This is a very key process central to septic shock,” describes Dr. McIntyre. “It’s an inflammatory cascade gone awry.”

“We used to think the cells facilitate their actions by grafting, through implanting themselves in wounded tissue or into the organs that are not working – say in sepsis,” says Dr. McIntyre. As it turns out they don’t make themselves at home, they just seem to “cross talk” to host cells – including cells that are responsible for killing pathogens – to regulate them and restore homeostasis. They are like the traffic cops of their microscopic world, and what’s more, within a few days they are gone from the system.

This is a critical area of research, not only because of the numbers of patients affected but the trickle down effect that results, such as days lost at work and extra labour for caregivers. Septic shock also comes with a hefty price tag. The estimated cost to the Canadian health care system is $4 billion.

“I think it’s important because there’s so much potential to help,” says Dr. McIntyre.

The results of the phase one trial will be published within the next few months and funding applications are already being made for the next phase of the trial. If the funding falls into place, the team hopes to begin the next phase by the middle of next year, and take one step closer to a treatment that may help thousands of people across Canada, and the world beyond.

This research was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Ontario Institute for Regenerative Medicine, the Stem Cell Network and The Ottawa Hospital Foundation

To find out more on how you can support stem cell research at The Ottawa Hospital visit ohfoundation.ca.