By Bob Grainger –

On the morning of November 1, 1871, the residents of the Westboro Beach area awoke to an immense fire consuming James Skead’s brand new steam sawmill on the shore of the Ottawa River.

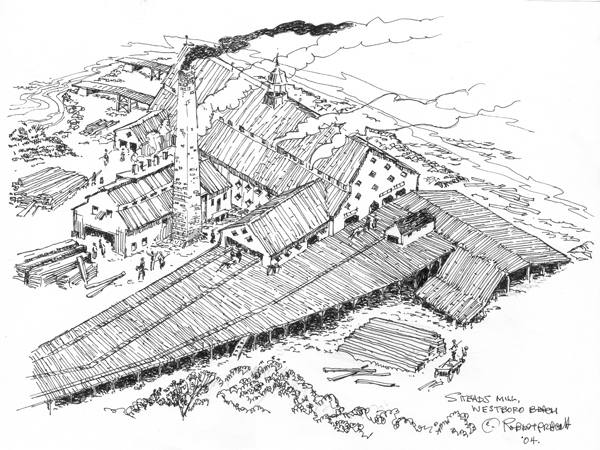

Senator Skead had constructed his mill just two years before, and it had been in full operation, producing a large amount of sawn lumber, lath and shingles. The main mill building was 145 feet long, 45 feet wide and three stories high. Within just a few hours, this building was reduced to a smouldering pile of ashes.

The forty men who worked in the mill were largely housed in a boarding house on the site, and they were roused to fight the fire. They concentrated their efforts on saving the powerhouse so that the steam engines could be used to pump water through the hoses to combat the flames. They couldn’t save the mill building, but they were able to keep the fire from reaching the bulk of the drying lumber in the piling ground.

Local residents were understandably worried about the fire spreading, and during this time, many harnessed horses and wagons to move their valuables to a safer location.

This part of Nepean Township was sparsely populated, with large areas of bush, and bush fires were frequent occurrences in the dry summer months. Fresh in the minds of the residents was the huge Ottawa Valley fire of 1870, in which hundreds of farms and several outlying villages just to the west in Nepean Township were completely destroyed.

Within days after the fire, James Skead made arrangements for the mill to be rebuilt, and it was operational by the summer of 1873. Care was taken in the design and operation of the mill to reduce the chance of fire. (For example, smoking by employees of the mill was grounds for immediate dismissal.) In order to refinance the building of the mill, Skead overextended himself financially. The timing of this was very bad, and he was forced to declare bankruptcy during the serious economic depression of the middle 1870s. E.B. Eddy, the Hull mill-owner, took over Skead’s second sawmill in 1880.

The mill functioned continuously under the direction of E.B. Eddy until the summer of 1888. Fire broke out in the afternoon of August 1, and was driven by a stiff breeze off the river. The fire spread very quickly over a wide area, and the rapid organization of a bucket brigade by the 200 employees was only able to slow the advance of the fire. The front of the fire moved steadily to the south, advancing on the stacks of drying lumber in the piling ground. Efforts were made to create a fire break by upsetting some of the sixteen-foot high piles of lumber, but the wind carried embers and flaming material well ahead of the front. This fire was a more serious blaze than that of 1871. Seven million board feet of lumber burned that afternoon; the equivalent of 700,000 boards. Each board was one inch thick, twelve inches wide and ten feet long.

The E.B. Eddy fire engine arrived on the scene from the city, and it was manoeuvred into position at the water’s edge. This was a movable steam engine, which used the power of the engine to take water from the river and propel it through the hoses to the site of the flames. Efforts were made to bring two other noteworthy municipal steam fire engines to the site – the famous Conquorer and the Union – but they arrived late in the afternoon and could do little to turn the tide by that time.

While there was no loss of life, there were about a dozen cases of serious burns as workers fought the conflagration and attempted to remove valuable equipment from the mill buildings. The fire caused damage as far inland as the CPR mainline, the present alignment of the Transitway. A few nearby houses were also consumed by fire.

The mill was not rebuilt again, and the smokestack of the powerhouse remained a local landmark for many years. The community suffered a serious economic blow with the loss of almost 200 jobs. Within a decade, the residents would change the name of the community from Skead’s Mills to Westborough.

Bob Grainger is a retired federal public servant with an avid interest in local history. KT readers may already know him through his book, Early days in Westboro Beach – Images and Reflections. He’s also part of the Woodroffe North history project and is currently working on the history of Champlain Park and Ottawa West. Do you have memories to share about the Westboro Beach fires? Send your email to stories@kitchissippi.com.

You can read Bob’s past Early Days columns right here.