By Bob Grainger –

Fire was a serious and ever-present fact of life in the Ottawa area in the 19th century, and it took three general forms: house fires in the winter time, bush fires in the dry periods of late spring and summer, and fires in the vast piles of drying lumber on the shores of the Ottawa River in the very heart of Ottawa and Hull.

So much progress has been made in the last one hundred years in the prevention and control of fires that it is difficult for the modern reader to fully appreciate the level of anxiety that was produced in the minds of 19th-century residents of the Ottawa area by the ever-present danger of fires. During dry periods in the summer, the pages of local newspapers contained many stories of wild bush fires in the area, and air was heavy with smoke. During the winter, the stories were about unfortunate families rendered homeless by house fires caused by over-taxed heating systems.

In a book entitled “The Ottawa Valley’s Great Fire of 1870,” author Terence Currie shared a gripping tale of the conditions leading to the start of the fire, the conflagration itself, and its repercussions.

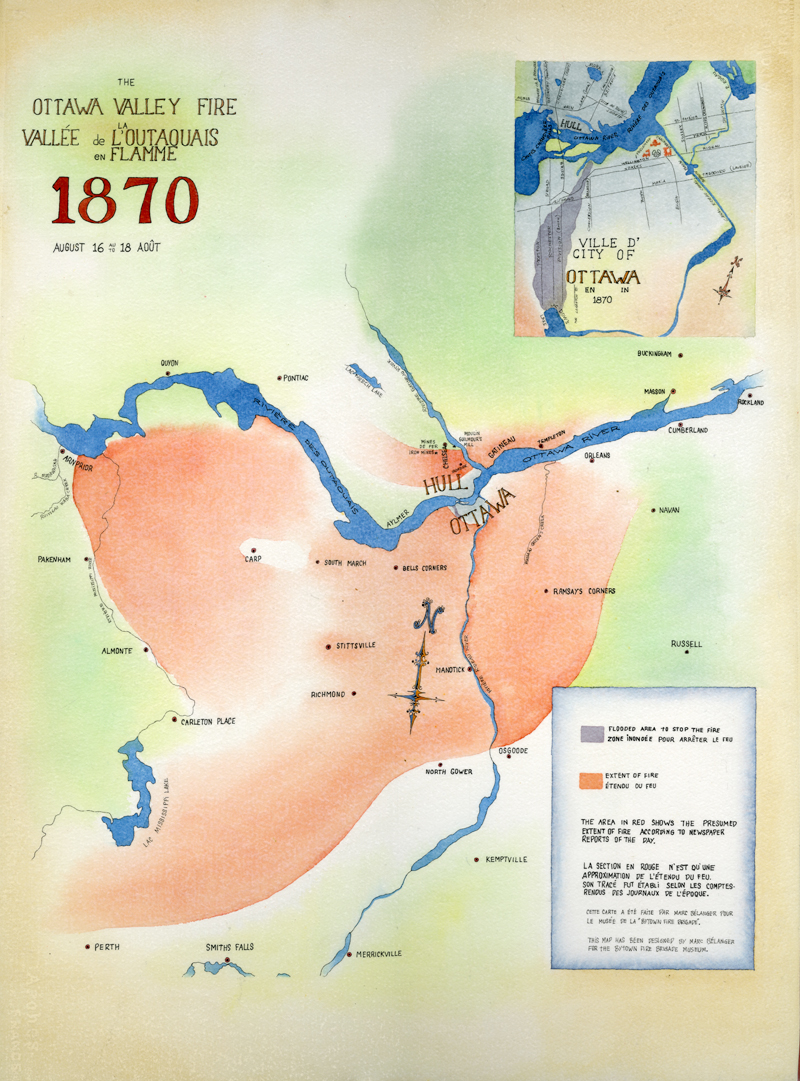

This map shows the general extent of the Great Fire of 1870. Image courtesy of Peter Ryan of the Bytown Fire Brigade.

Brush fires were a fact of life in the Ottawa Valley during the latter half of the 19th century. Farmers were always in the process of clearing their lands; burning dead trees and brush that littered the landscape. In general, they were careful to pick the right conditions for burning brush – cool windless days. But there was always a risk of a catastrophic fire, even on a seemingly perfect day.

The summer of 1870 was very dry, and ultimately set the stage for a major inferno. On August 17 of that year, a railway work gang lost control of a brush fire on the Canada Central Railway just north of Almonte. Very strong winds from the south propelled the front of the fire to the north, toward Pakenham and Arnprior. A day later, the high winds continued but shifted to the west, and the fire raged eastwards on a long north to south front. Residents of Carleton and Lanark counties saw the advancing smoke and flames and picked up their valuables and moved by whatever means possible towards the safety of Ottawa to the east. The fire was racing towards Ottawa and the city itself was filled with smoke, cutting visibility almost to zero.

The western side of Ottawa was threatened but then saved by breaching a part of the St. Louis dam on the north edge of Dow’s Lake. This allowed the water of the lake to flow down Preston Street, forming a shallow lake that protected the western flank of the city.

The map on the left shows the extent of the fire, from Arnprior, Almonte and Perth on the west, across the Rideau River to the outskirts of Orleans on the east, from North Gower and Osgoode on the south, and across the Ottawa River.

There were local variations on the extent of the damage. Villages like Stittsville and Bell’s Corners were entirely consumed by the fire. Others, like Carp and Richmond, were mostly spared because the surrounding deeper and more intensely cultivated soils slowed the advance of the fire. In total, about 200 square miles (125,000 acres or 50,000 hectares), were affected by the fire. About 20 people lost their lives, and eight thousand became homeless. The worst of the fire took place in just several days following the 17th of August, and it continued to smoulder until heavy rains in September.

A considerable amount of farmland to the west of Ottawa was rendered sterile and permanently unproductive by the fire, and the owners of these farms were forced to move to other locations.

Terence Currie’s book is based on very detailed research into the public records that remain from that time, and is replete with fascinating stories of individual heroism, ingenuity, and unfortunately, tragedy, during those fateful days in the summer of 1870.

The City of Ottawa Archives is currently presenting an exhibit entitled “Ashes” at the James Bartleman Centre, 100 Tallwood Dr., off Woodroffe Avenue South. The exhibit contains information on the legendary fires that shaped the capital and continues until March 21, 2015.

Bob Grainger is a retired federal public servant with an avid interest in local history. KT readers may already know him through his book, Early days in Westboro Beach – Images and Reflections.He’s also part of the Woodroffe North history project and is currently working on the history of Champlain Park and Ottawa West. Do you have any memories to share about early Kitchisisppi? If so we’d love to hear them. Send your email to stories@kitchissippi.com.