The focus of last month’s column was the Trocadero dance hall at Westboro Beach. This month, despite the snow and sub-zero temperatures outside, we’re continuing our look at the development of Westboro Beach and the community’s involvement in regards to its use.

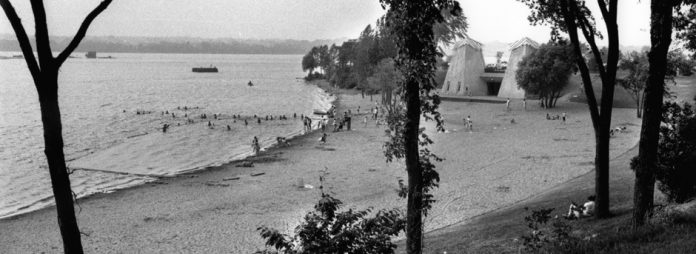

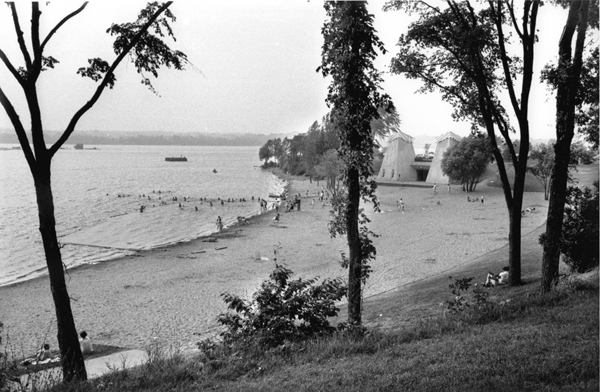

It is impossible to date the first use of the river at Westboro Beach for recreational purposes. The workers at James Skead’s mill undoubtedly found themselves in the river on occasion, whether by accident or on purpose, but the first documented and datable evidence comes from the early 1920s with a photo of the bathers enjoying a waterslide in the shallow water. For the more adventuresome, there was another taller slide anchored out in deeper water. The slides were community built using available materials, such as logs lying abandoned along the shore.

The “Westboro Swimming Club” was created in the early 1920s and incorporated under the provincial law, although it was really a community social organization, planning dances and other social events at the beach. Membership cost $5.00. The Club hosted races and swimming lessons for the young people in the neighbourhood, organized the construction of water slides and rafts, and built an open-air dance platform.

The Police Village of Westboro was also involved in activities at the beach, and as early as 1916, ordered the purchase and installation of two 12 x 17 tents “for the convenience of bathers.”

In these early years, Westboro Beach was not much of a beach. There was very little sand – just dirt and mud, sawdust and bark from the mill – amid rocks and shale. The Swimming Club had children pulling weeds to keep the beach relatively accessible for swimming. (The sand came later, in the 1950s.)

During the 1930s, the ownership of the beach lots fell increasingly into private hands, particularly those of Sam Ford. Sam owned the local snack bar and rented several cottages at the beach, and organized many activities to attract people to the beach and to the Trocadero dance hall. He organized carnival days of games of skill and chance, swimming races, and visual extravaganzas that included local youth diving through flaming circles of fire. He also constructed large concrete blocks at the water’s edge for party lights that were used during evening events.

Regardless of its popularity as a gathering place, Westboro Beach was neither a pristine stretch of sand, nor a safe place to swim. The logging industry left behind a legacy of submerged logs and structures, which were dangerous to unsuspecting swimmers. The safest part of the beach was the shallow part at the end of Lanark Avenue, but even here, water-logged timbers, unexpected holes, and the remains of the piers (or rock-filled cribs) caused casualties. More advanced swimmers migrated to the remains of Skead’s Mill, at the downstream end of the current Kitchissippi parking lot.

Normally submerged, but visible during low water levels in the summer, are the remains of a rock-filled crib some 75 to 100 meters offshore. This crib was used to anchor the boom-logs, which controlled the timber on the river. During the 1930s and 1940s the top of this crib was 5 or 6 feet above water level and was a favourite destination for older youth, but there was a very rapid current between the shore and the crib, which posed a serious danger to swimmers. There were also reports of underwater structures related to the mill, which trapped and injured swimmers. There were a half-dozen drowning fatalities in each decade of the early years, but they weren’t limited to summer swimmers. Several small children drowned when they fell through the ice in the winter.

One particular drowning death had far-reaching implications for the neighbourhood. On a warm evening in June of 1949, James Allan Campbell, a local teenager, tripped on a log and hit his head and slipped unconscious into the water. His body was not recovered until the following afternoon. His death stimulated a massive reaction on the part of his friends and classmates, and ultimately led to lasting improvements in the area of community recreational resources. His friends formed the J.A.C. Club – which stood for James Allan Campbell – and they spent many hours cleaning the beach of debris and collecting names for a petition to pressure the Township and the City into improving the beach and creating other neighbourhood recreational resources, such as Dovercourt.

–

Bob Grainger is a retired federal public servant with an avid interest in local history. KT readers may already know him through his book, Early days in Westboro Beach – Images and Reflections. He’s also part of the Woodroffe North history project and is currently working on the history of Champlain Park and Ottawa West.

Tell us, what would you like to read about in his next column?

- The disappearance of Banting Avenue

- Kitchissippi’s golf course

- Railway accidents in the neighbourhood

Cast your vote by leaving a comment below or sending an email to stories@kitchissippi.com.